The Pillar Testament

Bka' chems ka khol ma

Introduction

This narrative purports to be the testament (bka’ chems) of the seventh-century emperor, Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po), which was retrieved from a hole in a pillar in Lhasa by Atiśa in around 1048. Davidson (2003) suggests that it must have been compiled in the twelfth century, using earlier sources, some of which are referred to in the text, by a writer from the Nyingma (rNying ma) tradition. He calls it ‘a summation of literary and cultural trends in the late-eleventh and mid-twelfth centuries’, and the basis for the development of Tibetan imperial mythology.

The early chapters discuss the history and lineage of the emperor’s family and the development of the Buddhist doctrine in Tibet. According to Davidson (2003), this is the first text in which Songtsen Gampo appears as an incarnation of Avalokiteśvara. These chapters discuss the training and empowerment of the king, including his creation of law. There then follow accounts of the missions by his minister, Gar, to Nepal and China, from where he brings back the two princesses to be the king’s wives. The Chinese Princess Wencheng brings the Jowo statue with her and the temple in Lhasa is established, followed by the spread and establishment of Buddhism throughout Tibet.

The text is referred to by Nyangral Nyima Öser and the Lde’u authors, and it is a source for the passages on law in the Mani Kambum.

Download this resource as a PDF:

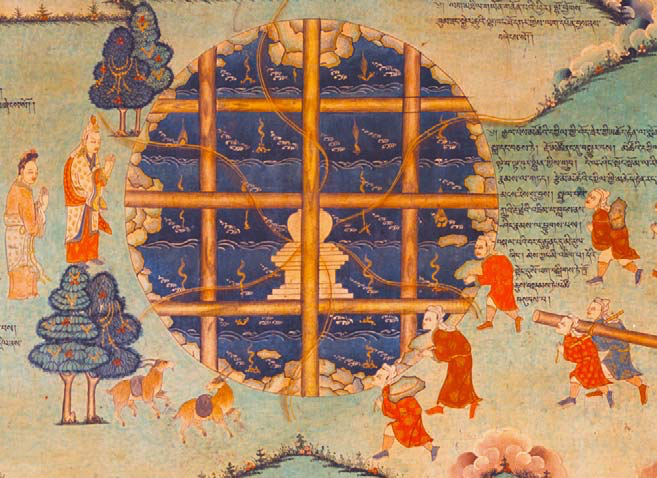

Founding of Jokhang, wall-painting in Norbulingka, Takten Migyur Potrang © André Alexander

Sources

A ti sha, sMon lam rgya mtsho (ed.) 1989. bKa‘ chems ka khol ma. Lanzhou: Kan su’u mi rigs dpe skrun khang. [This edition is based on two manuscripts, kept at the Beijing Mi rigs dpe mdzod khang (Nationalities Library), and at bLa brang bkra shis ’khyil monastery, in Gansu province.] BDRC: W20856.

Literary Arts in Ladakh. 1972. Darjeeling: Kargyud sungrab nyamso khang, vol 1, pp. 363–474. BDRC: W20515

Ma ’ongs lung bstan gsal ba’i sgron me. 1973. Leh: Tondup Tashi. Vol.1, pp. 613–809. BDRC: W1KG22374

Manuscript photos BDRC W00KG010083 [provenance not given].

References

Davidson, Ronald M. 2004. The Kingly Cosmogonic Narrative and Tibetan Histories: Indian Origins, Tibetan Space, and the bka’ chems ka khol ma Synthesis. Lungta 16: 64–83.

Eimer, H. 1983. Die Auffindung des bKa’ chems Ka khol ma. In E. Steinkellner and H. Tauscher (eds), Proceedings of the Csoma de Körös Memorial Symposium. Vienna: Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien, vol 1, pp. 28–32.

Jamgön Mipham Rinpoche. (Erik Pema Kunsang, trans.) 2000. Gateway to Knowledge. Hong Kong: Rangjung Yeshe, vol. 2.

van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1996. Tibetan Historiography. In J. Cabezón and R.R. Jackson (eds), Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre. Ithaca: Snow Lion, pp. 39–56.

Mills, Martin. 2012. Ritual as History in Tibetan Divine Kingship: Notes on the Myth of the Khotanese Monks, History of Religions 51: 219–20.

Sørensen, Per. 1994. Tibetan Buddhist Historiography: The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Vostrikov, A.I. (H.C. Gupta, trans.) 1994. Tibetan Historical Literature. Abingdon: Routledge.

Warner, Cameron. 2011. The Genesis of Tibet’s First Buddha Images: An Annotated Translation from the Three Editions of the Vase [-shaped] Pillar Testament (bka’ chems ka khol ma). Light of Wisdom, 1: 33–45.

Outline

The Tibetan text, page references, and chapter headings are from the 1989 Lanzhou edition.

Chapter 1: Training within the deity realm (sambhogakāya)

Chapter 2: Establishing a physical body

Chapter 3: Training within the manifestation realm (nirmāṇakāya)

Chapter 4: Training with material wealth

Chapter 5: History of the family lineage and the royal lineage

Chapter 6: The holy Buddhist dharma coming into existence at the time of Lhato Tori (Lha tho tho ri)

Chapter 7: History of the father, King Namri Songtsen (gNam ri srong btsan)

Chapter 8: King Songtsen Gampo (Srong btsan sgam po) is completely empowered in body, speech and mind

Chapter 9: The monk manifestation invites the tutelary deity

Chapter 10: Invitation of Princess Tritsun (Khri btsun)

Chapter 11: Invitation to Princess Wencheng (Ong cong)

Chapter 12: Princess Wencheng Gongzhu performs geomancy on Mount Rinchen pung (Rin chen spungs)

Chapter 13: The Eleven-faced Compassionate One trains the ghosts and demons of the snowy land

Chapter 14: Princess Tritsun builds the lower part of the Lhasa temple

Chapter 15: The completed virtuous activities of Songtsen Gampo and the activities of his six consorts

Chapter 16: On the history and future of the teaching of the doctrine in Lhasa

Extracts

Chapter 9: Monk manifestation Akarmati (A kar ma ti) invites the tutelary deity.

After Tonmi Sambhota (Thon mi sam bho ta) introduces the Tibetan script, he translates several, works which contain material on avoiding the ten non-virtues. King Songtsen Gampo is taught to read and spends four years in seclusion.

[p. 108–09]

དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བྱེད་པའི་ཁ྄ིམས་ཡིག་དང་བཅས་པ་བཞི་བཞུགས་ནས་འདུག དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཡི་གེ་བསླབས་ནས་ལོ་བཞིར་ཕྱིར་མ་བྱོན་པས། བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ན་རེ། རྒྱལ་པོ་འདི་ལོ་བཞིར་མ་འབྱོན་པ་གླེན་པ་ཅི་ཡང་མི་ཤེས་པ་ཡིན། བོད་འབོངས་རྣམས་སྐྱིད་པ་འདི་ངེད་བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་བྱས་སོ་ཟེར་བས། རྒྱལ་པོས་དེ་སྙན་དུ་གསན་ནས། ང་ལ་གླེན་པ་ཟེར་ན་འབངས་རྣམས་མི་ཐུལ་སྙམ་ནས། འདི་སྐད་ཅེས་གསུངས་སོ། ཁྱེད་བློན་འབངས་ཐམས་ཅད་ངའི་རྩར་འདུས་ཤིག རྒྱལ་པོ་ང་ཕོ་བྲང་གཅིག་ཏུ་བཞུགས་ནས་འཕོ་སྐྱས་མི་བྱེད་ན་སྐྱེད་༼སྐྱིད་༽ པ་ཡིན་པ་ལ། ཁྱེད་བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ན་རེ་བོད་འབངས་རྣམས་སྐྱིད་པ་དེ་ཉིད་བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་བྱས་པ་ཡིན་ཟེར་བས། བློན་འབངས་རྣམས་ལ་བཀའ་བསྒོ་བ་ཡིན་ནོ། ད་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅའ་དགོས། སྔོན་ཡང་ཁྲིམས་བཅའ་དགོས། སྔོན་ཡང་ཁྲིམས་མེད་པས་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ཕྲན་བཅུ་གཉིས་མཐར་ཡན། ད་ཡང་ཁྲིམས་མེད་ན་ཉེས་པ་སྣ་ཚོགས་ཀུན་བྱེད་པས། ངའི་དབོན་སྲས་ཞང་བློན་རྣམས་སྡུག་བསྔལ་བར་འགྱུར་བས། ངའི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་སུ་གཏོགས་པའི་མི་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། སྲོག་མ་བཅད་ཅིག་བཅད་ན་སྟོང་འདོད་མ་རྐུ་རྐུས་ན་འཇལ་འདོད། མ་རྡུང་མ་འཕྲོག་ཅིག འཕྲོག་ན་འཇལ་འདོད། བྱི་བྱས་ནི་བྱི་རིན་འདོད། བརྫུན་དང་ཕྲ་མ། ངག་ཁྱལ། བརྣབ་སེམས། གནོད་སེམས། ལོག་ལྟ། ཁྲིམས་དང་འགལ་བའི་ལས་རྣམས་གང་བྱས་ལ། དེ་རྣམས་ཀུན་ལ་ཆད་པ་གང་ཐོབ་གཅོད་བྱ་བ་ལ་སོགས་པ་གསུངས་པས།

[The translators] completed the four legal texts concerning the laws of the ten virtues.1 Then the king studied the script, and did not appear for four years. The ministers said: ‘The king hasn’t appeared for four years. He is an ignorant fool. The happiness of the Tibetan people is down to us, the ministers.’

When the king heard this, he thought: ‘If I am said to be foolish, I will not be able to control my subjects.’ Then he said: ‘You, ministers and subjects, assemble in my presence. When I, the king, was living alone in my palace, and I did not travel around, I was making progress.2 You, ministers, have said that the subjects are made happy by the ministers, so I will give orders for both ministers and subjects. Now, I need to make laws based on the ten virtues. Previously, it was also necessary to have laws, but since there were none throughout the twelve regions of the Tibetan realm, and since there are still none, bad behaviour is likely to occur everywhere. My descendants and the Zhang ministers will suffer. The people of my kingdom must not kill—if they kill, compensation must be given; they should not steal—if they steal, a fine must be paid; they must not assault nor rob—if they rob, compensation must be paid; those who engage in sexual misconduct—they must pay compensation; they must not lie nor use divisive speech, gossip, be covetous, bear ill-will, or have wrong views. If they do anything that contravenes the law they must be stopped and suitable punishment must be applied.’

བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ན་རེ། རྒྱལ་པོ་འདི་ཐུགས་སྒམ་པོ་ཅིག་འདུག་གོ་ཟེར་ནས་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་སྲོལ་གཞུང་བཟང་པོ་སྲོང་བ། ཐུགས་ཡང་སྒམ་པས་ན་མིང་དང་མཚན་ཡང་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོར་བཏགས་སོ། མི་ཆོས་ཆེན་པོ་བཅུ་དྲུག་ལ་དཔེ་བླངས་ནས་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས། དེ་བརྟན་པར་བྱས་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོའི་ཐུགས་དགོངས་ལ། ད་ནི་ངའི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་འདིར་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་བྱར་བཏུབ་པས། ཆོས་བྱེད་པ་ལ་ཡི་དམ་གྱི་ལྷ་དགོས་པས།

The ministers said: ‘The king is a person with a profound mind.’ He had put in place (srong) good government based on traditions of the true doctrine, and he was of profound (sgam) mind, so he was given the name and title King Songtsen Gampo (Straight Powerful Profound).

Adopting the example of the sixteen important human customs (mi chos chen po), he made the law of the ten virtues and created stability. King Songtsen Gampo thought to himself: ‘Because I ought to establish the true doctrine in this royal kingdom of mine, I need a tutelary deity in order to practise the dharma’.

Chapter 10: The Invitation to Princess Tritsun (Bal bza’).

The minister Gar (mGar stong rtsan) is sent to Nepal, where he meets the king and asks him to give his daughter, Princess Tritsun, to be the wife of Songtsen Gampo. He offers a present of armour, saying:

[p. 131]

འཁྲུག་པའི་གཡུལ་དུ་ཞུགས་པའི་དུས་སུ་ཁྲབ་འདི་གོན་ནས་གཡུལ་དུ་ཞུགས་ན་གཡུལ་ལས་རྒྱལ་བར་འགྱུར་རོ། །ཁྲབ་འདི་ངོ་ཚར་ཆེ་ཞིང་འཛམ་བུའི་གླིང་ན་གོང་ཐང་འདེབས་སུ་མེད་པས་འདི་འབུལ་བ་ལགས། མཐའ་འཁོབ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ལྷ་ཅིག་སྲས་མོ་བཙུན་མོར་འབུལ་བར་ཞུ་བྱས་པས། བལ་པོའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཁྲོས་ཏེ། ཨ་པ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་བློན་བརྙས་ཆོས་རེ་ཆེ། གཉེན་བྱ་བ་བསྙམ་པོ་ལ་འདོགས་པ་ཡིན། ཁྱེད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་བས་ང་བཟང་ང་ལ་སངས་རྒྱས་འོད་སྲུངས་ཀྱི་དུས་ནས་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ཡོད། སྐུ་གསུང་ཐུགས་ཀྱི་མཆོད་གནས་ཡོད། རྒྱལ་པོ་ཀྲི་ཀྲིའི་རིང་ནས་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་སྤངས་ནས། དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་གསེར་གྱི་གཉའ་ཤིང་ལྷ་བུ་ཡོད། ལོངས་སྤྱོད་ནི་ཐབ་ཏུ་དུ་བ་སྔོ་མི་ཆད་པ། སླ་ང་ཏིང་མི་ཆད་པ་རང་འཐག་འུར་མི་ཆད་པ་ཡོད། ཁྱོད་བོད་ཡུལ་བྲེ་ཏ་པུ་རིའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་དེ་ཚོ་གང་ཡང་མེད་པས་ང་དང་གཉེན་ཟླར་མི་འོང་། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་མེད་པའི་ཡུལ་དེར། རྡུང་འཕྲོག་དང་རྔན་ཅན་ཡོད་པས་སྐྱིད་པོ་མེད། བུ་མོ་མི་སྟེར། ད་ཁྱེད་རང་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་སྤངས་ནས། དགེ་བ་བཅུ་དང་དུ་བླངས་ནས་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་གསེར་གྱི་གཉའ་ཤིང་ལྟ་བུའམ། ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དར་གྱི་མདུད་པ་ལྟ་བུ་ཅིག་འཆའ་ནུས་ན། ལྷ་ཅིག་བལ་བཟའ་འདི་སྟེར། མི་ནུས་ན་མི་སྟེར། ཁྱེད་རང་ཕར་ལ་སོང་ལ་རྗེ་ལ་དྲིས་ལ་དེའི་ལན་ཁྱེར་ལ་ཤོག་དང་གསུངས་པས།

‘Since you live in an unstable region, if you wear this armour at times of war, you will be victorious over an armed horde. This armour is remarkable, there is nothing in the world more valuable, and I offer it to you. I offer it to the king of Tibet’s neighbour in exchange for your noble daughter, the princess.’

The king of Nepal became angry: ‘Ha! The king of Tibet and his ministers have an exaggerated view of themselves—they present themselves as kinsmen of equal status. I am a better king than yours. I have had the true doctrine since the time of Buddha ’Od srungs (Dīpaṃkara). I am an object of veneration in body, speech, and mind. Having eliminated the ten non-virtuous actions in the reign of King Kri kri, we have maintained the royal law of the ten virtues, like a golden yoke; our material resources are like the blue smoke produced continuously in the hearth; roasting pans are constantly in use; and our mills are always busy. Your Tibetan king, Bre ta pu ri, does not have any of these. So there will be no marital arrangements with me. The lawless country of Tibet, where there is violence, robbery, and rowdiness, is not pleasant. I will not grant you my daughter. If, after you have eliminated the ten non-virtues and adopted the ten virtues, you can set in place a royal law, like a golden yoke, and a religious law, like a silken knot, then I will give you Princess Bal bza’; if this cannot be done, I will not grant her. Go away and give me your answer to that question later.’

The minister then gives the Nepalese king a golden box and, referring to the relations between their two countries, he explains that it contains a message from Songtsen Gampo. The king opens the box and discovers in it a text written in golden Nepalese script. In the text, Songtsen Gampo describes his history:

[p. 132]

ང་རིགས་རྒྱུད་མི་ངན་རིགས་རྒྱུད་བཟང་། ང་ལ་ཁྲིམས་མེད་ཟེར་ཏེ།

ཁྱེད་ཁྲིམས་ལ་དགྱེས་ཤིང་མཉེས་ནས་ལྷ་ཅིག་ཁྲི་བཙུན་བཀའ་ཡིས་གནང་ན། ངས་སྐུ་ལུས་ཀྱི་བཀོད་པ་ལྔ་སྟོང་དུ་སྤྲུལ་ལ། བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་སུ་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དང་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་ཉི་མ་གཅིག་ལ་བཅོས་ལ་བཞག་གི དེ་འཇིགས་བསམ། དེ་ལ་ཅིག་ཁྲི་བཙུན་མི་སྟེར་ན། ངས་སྤྲུལ་པའི་དམག་གིས་བལ་ཡུལ་འཇོམས་ཤིང་བརླག་པར་འགྱུར་རོ་ཞེས་བྱ་བའི་ཡི་གེ་བྱུང་བས།

‘My family lineage has contained bad people, but it is good. It is said that I have no law code. Since the law pleases and delights you, if you order the release of Princess Khri btsun, I will manifest an arrangement of 5,000 bodily forms. You should know that in the Tibetan kingdom I have instigated the creation of the royal law and the religious law as if they were one sun. However, if you do not give me Princess Khri btsun, my army of manifestations will conquer Nepal and destroy it.’

Later, the Nepalese king changes his mind and tells his daughter that she must go to Tibet.

[p. 137]

ཡབ་རྒྱལ་པོས་ལྷ་ཅིག་ཁྲི་བཙུན་ལ། བུ་མོ་ཁྱོད་བོད་ཡུལ་དུ་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོའི་བཙུན་མོ་ལ་འགྲོ་དགོས་བྱས་པས། སྲས་མོ་ལྷ་ཅིག་ན་རེ། ཡབ་དང་ཡུམ་དང་མི་འཕྲད་པ། ཁྲིམས་དང་ཆོས་དང་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་མེད་པའི་ས་ཡུལ་དེར་ང་མི་འགྲོ་ཟེར་བ་ལ། ཡབ་རྒྱལ་པོ་ན་རེ། དེས་མི་ཕན་བུ་མོ་ཁྱོད་བོད་དུ་མ་ཕྱིན་ན། བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་མོས་སྤྲུལ་པའི་དམག་བསམ་གྱིས་མི་ཁྱབ་པ་དྲངས་ནས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར་ཐམས་ཅད་འཇོམས། ང་གསད་ཁྱོད་ཁྱེར་བས། དེ་བས་ན་ད་ལྟ་ནས་འགྲོ་རྩིས་བྱས་པ་དྲག་གསུངས་པས།

The king said to Princess Khri btsun: ‘Daughter, you must go to be queen of the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo.’ Princess Khri btsun said, ‘I will not be estranged from my father and mother. I will not go to a country that has no law, no religion, and no material resources (khrims dang chos dang longs spyod med).’ Her father, the king, replied sharply: ‘That is not good, my daughter. If you do not go to Tibet, the Tibetan king will lead an incredible army of manifestations and destroy all our cities, kill me, and carry you off. Therefore, you must make plans to go.’

Chapter 11: Invitation to Princess Wencheng (Ong cong)

The minister Gar then visits China in order to ask for the hand in marriage of the king’s daughter, Wencheng, for Songtsen Gampo. The narrative initially follows a similar pattern to that of his mission to the king of Nepal, with the same discussion and promises about the laws of the ten virtues.

[p. 157, 170–71]

ཁྲིམས་ཡོད་ཆོས་ཡོད་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་ཡོད་

Law, religion, and material wealth.

These three are mentioned several times as features of a good kingdom with a religious king.

Chapter 14 Princess Tritsun (Bal bza') builds the lower house of the Lhasa (Ra sa) temple

[p. 235]

དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོའི་ཐུགས་དགོངས་ལ་མི་མ་ཡིན་མོའི་ཡན་ལག་དང་ཉིང་ལག་སོར་མོ་རྣམས་གནོན་པར་བྱ་བའི་ཕྱིར་མཐའ་འདུལ་དང་། ཡང་འདུལ་གྱི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་རྣམས་ནི་བཞེངས། ས་དགྲ་རྣམས་མཐའ་བཞིའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་བཞེངས་པ་དེས་སྲིན་མོའི་མགོ་དང་སུག་བཞི་རྩ་ལག་རྩ་བྲན་དང་བཅས་པ་རྣམས་ལེགས་པར་གནོན་ནས། ར་སའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་བཞེངས་སུ་བཏུབ་པར་མཁྱེན་ནས། སྐུ་ལུས་ཀྱི་བཀོད་པ་ལྔ་སྟོང་དུ་སྤྲུལ་ནས། སྤྲུལ་པའི་མི་མང་པོ་སྐྱེས་པ་སྟོང་ཐམས་པས་ནི་ཕ་སྤྲེའུ་སྒོམ་དང་། མ་བྲག་སྲིན་མོ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་བུ་བརྒྱུད་མི་མ་རུང་བ་ཕལ་བ།

མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ལས་བྱེད་པ་རྣམས་ལ་ཆད་པ་གཅོད་པའི་ཆེད་དུ་ཕོ་བྲང་གི་ལྕགས་རིའི་ཕྱི་ནང་ཐམས་ཅད་དུ་ཆད་པ་གཅོད་མཁན་གྱི་མིས་ཁེངས་པར་བྱས་ནས། མགོ་འབྲེག་པ་དང་། མིག་འདོན་པ་དང་། པགས་པ་བཤུ་བ་དང་། རྐང་ལག་འབྲེག་པ་དང་། ཨན་བན་ལ་འདོགས་པ་དང་། མེ་ཐབ་ཏུ་འཇུག་པ་དང་། སའི་ཆད་པ་དང་། མེའི་ཆད་པ་དང་། རླུང་གི་ཆད་པ་དང་། ལྕགས་རྒྱག་པ་དང་། ཤིང་རྡོས་རྒྱག་པ་དང་། ས་དོང་དུ་འཇུག་པ་དང། དེ་ལ་སོགས་པའི་ཆད་པ་སྣ་ཚོགས་པ་མང་པོ་གཅོད་དོ།

Then King Songtsen Gampo thought to himself: ‘In order to pin down the main limbs, the secondary limbs, and the digits of the female spirit, I will subdue the borderlands and build temples of subjugation. By building temples at the four extreme geomantic positions, the demoness’s head and four limbs—the main and secondary limbs—will all be properly pinned down. So it is appropriate to build the Ra sa temple.’

After he manifested 5,000 bodily forms, many of the men born as manifestations—one thousand in all—were as unruly as the descendants of the father monkey meditator hermit and the mother rock demoness. In order to punish non-virtuous actions, all places within the iron mountains encircling the palace were filled with men skilled in punishment. Various punishments were meted out, such as cutting off heads, plucking out eyes, flaying the skin, cutting off feet and hands, binding feet in stocks, throwing people into hearths, earth punishments, fire punishments, air punishments, beating people with iron, hitting people with wood or stones, putting them in a hole in the ground, and so forth.

The text describes the temple interiors, with twelve mandalas in twelve parts of the Lhasa temple. King Songtsen Gampo then addresses his Nepalese Queen, Princess Tritsun.

[p. 258]

དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་པས་བོད་ཡུལ་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་སེམས་ཅན་རྣམས། དེ་བཞིན་གཤེགས་པའི་གདུལ་བྱར་མ་གྱུར་པ་བཀའ་ལ་ཡིད་མི་ཆེས་པས་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་བདུད་རྩི་འཐུང་དུ་མི་བཏུབ་པ། རིག་པའི་ཆོས་ལ་བློ་མི་འགྲོ་བ། བསླབ་པ་གསུམ་ལ་བསླབ་ཏུ་མི་བཏུབ་པའི་སེམས་ཅན་འདི་རྣམས་ངའི་ཆོས་ཁྲིསམ་དང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིསམ་ཀྱིས་འདུལ་བ་ཡིན་པས་དེ་ལྟ་བུའི་རྒྱུད་རིས་ཀྱང་བྲིའོ།

‘Since the sentient beings of the snowy land of Tibet have not become trainees of the De bzhin gshegs pa [Buddha] and do not have faith in his commandments, they will not be able to imbibe the nectar of the true doctrine. Their intellect does not lean towards religious knowledge. These sentient beings, who will not be suitable for instruction in the three forms of training [Buddhist morality, meditation, and wisdom], will [nevertheless] be tamed by my religious laws (chos khrims) and royal laws (rgyal khrims), and for that reason, they have been written on a wall panel.’

The king goes on to add that such writing will bring the ‘ignorant sentient beings of the snowy land’ to study and develop faith.

Chapter 16: On the subsequent history of the teaching of the doctrine in Lhasa

[p. 302–05]

ཡང་ལི་ཡུལ་གྱི་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས། འཇམ་དཔལ་ལོ་བཅུ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་བར་དུ་བསྒྲུབས་པས་མ་འགྲུབ་ནས། འཕགས་པ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་རེ་ཆུང་ཞེས་སྨྲེ་སྔགས་བཏོན་པས། འཇམ་དཔལ་ནམ་མཁའ་ལ་བྱོན་ནས་ང་དང་ཁྱེད་གཉིས་ལས་འབྲེལ་མེད། ཁྱོད་གཉིས་དང་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་ལས་འབྲེལ་ཡོད་པས་ཁོང་ད་ལྟ་བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ན། རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོར་སྐུའི་སྐྱེ་བ་བཞེས་ནས་ཡོད་ཀྱིས། ཁྱོད་གཉིས་དེར་ཤོག་ཅེས་ལུང་བསྟན་ཏོ། །དེར་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་བོད་ཡུལ་ཕྱོགས་གང་ན་ཡོད་ཆ་མེད་ཀྱང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་མོས་པ་བྱས་ནས་ཡོང་བ་དང་། སྟོད་ལུངས་མདའ་མར་ཡོང་བས། དེར་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པའི་མགོའི་ཕུང་པོ་དང་། མིག་ཕྱུང་བའི་ཕུང་པོ་དང་། མི་རོའི་ཐང་མ། ཁྲག་གི་འདོ་བ་ཆུ་བྲན་ཙམ་དུ་འདུག་པ་ལ་། འདི་ཅི་ཡིན་བྱས་པས། བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཁྲིམས་བཅད་པ་ཡིན་ཟེར། དེར་ཁོང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་བསམ་པ་ལ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ། སྤྲུལ་པ་ནི་ཅིའི་སྤྲུལ་པ། སྡིག་སྤྱོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་འདི་ལྟ་བུ་ཅིག་འདུག་སྙམ་དུ།

Two Khotanese novice monks had been practising ʼJam dpal (Mañjuśhrī) for twelve years, but they were not successful and lamented that ‘holy compassion offers little hope’. ʼJam dpal pronounced from the sky: ‘I have no connection with you, but since you both have a connection with Thugs rje chen po (Mahākarunā), and he is now in the kingdom of snowy Tibet, born in the form of King Songtsen Gampo, you should go there.’ Then the two novices made a wish about the king and, despite not knowing in which direction Tibet lay, they set off and arrived at sTod lungs mda’ ma. There they found a heap of heads from the king’s executions, a heap of eviscerated eyeballs, human corpses strewn around, and a stream of flowing blood. ‘What is this?’ they asked. They were told: ‘These are the legal punishments meted out by the king.’

The pair thought: ‘The Tibetan king is an emanation, but what kind of emanation is a king who carries out such heinous acts?’

རྒྱལ་པོ་ད་ལྟ་གང་དུ་བཞུགས་དྲིས་པས། ལྷ་ས་ན་བཞུགས་ཟེར་བས། དན་འབག་གི་དགུང་སེབ་ཅིག་ན་ཡར་ཕྱིན་པ་དང་། དེར་ཡང་མགོའི་ར་བ། མིག་གི་ཕུང་པོ། རྐང་ལག་གི་བཅད་གཏུབས། ལ་ལ་མེ་ལ་གཏུག་པ་དང་། ལ་ལ་ཕྱེད་མ་བྱེད་པ་དང་། ལ་ལ་གསལ་ཤིང་ལ་སྐྱོན་པ་ལ་སོགས་པའི་རིགས་མི་འདྲ་བ་མང་པོར་སྤྱོད་པ་མཐོང་བས། ལིའི་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་ཤིན་ཏུ་བྲེད་དེ། འཇམ་དཔལ་ཡང་བདུད་དུ་ཐལ། སྤྲུལ་པ་དེ་ཅིའི་སྤྲུལ་པ། སྡིག་སྤྱོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་འདི་འདྲ་བ་ཅིག་འདུག་སྙམ་ནས་ཕྱིར་ལོག་ནས་བྱོན་ནོ།།

When they asked where the king was residing, they were told, ‘He is in Lhasa.’ They went on to a market3 in Dan ʼbag. There they also saw a wall of heads, a heap of eyeballs, and severed hands and feet, people being grilled in a fire, some being ground into pieces, some impaled on sticks, and many other such things. The two novices were very frightened, and thought that ʼJam dpal was acting like a demon, and that the manifestation—whatever it may have been—was of such a sinful king that they turned back.

རྒྱལ་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་ཡི་ཆད་པར་མཁྱེན་ནས། བློན་པོ་ཅིག་ལ་རྟ་ནག་པོ་མདོངས་ཅན་བསྐྱོན་ནས། ཁྱོད་ཀྱིས་དན་འབག་ཐང་ན་མར་ལ་འོ་སྐོལ་པ་དང་ཆ་ལུགས་མི་འདྲ་བའི་མི་མགོ་ལ་སྐྲ་མེད་པ། གོས་སེར་པོ་གྲུ་བཞི་གོན་པ་གཉིས་ཡོད་ཀྱིས། དེ་ངའི་དྲུང་ན་ཤོག་བགྱིས་ཤིག་ཅེས་དེར་བཏང་ངོ་། །བློན་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་འཛིན་དུ་སོང་བ་དང་། ཁོང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་བསམ་པ་ལ་ད་ནི་ངེད་གཉིས་ལ་ཡང་ཆད་པ་གཅོད་པར་འདུག་སྙམ་ནས་བྲེད་པར་གྱུར་ཏོ། །དེ་ནས་བློན་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་ཁྲིད་ནས་ཕྱིན་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ནུབ་སྒོའི་ནེའུ་ཁ་ན་བཞུགས་པ་དང་མཇལ་ནས། ལིའི་སྐད་དུ་ཁྱེད་གཉིས་འདིར་ཅི་ལ་འོངས་དྲིས་པས། དེ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་ཇི་ལྟར་ཡིན་པའི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་བརྗོད་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཞལ་ནས་ཁྱོད་གཉིས་ཨཱརྱ་པ་ལོའི་ཞལ་ལྟ་བར་འདོད་དམ་གསུངས་པས། ལྟ་བར་འཚལ་ལགས་ཞུས་པས། རྒྱལ་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་ལྷ་སའི་ནེའུ་ཆུང་བྱེ་མའི་གླིང་དུ་ཁྲིད་ནས། དབུའི་ཐོད་པ་བཤིག་ནས་ཨཱརྱ་པ་ལོའི་ཞལ་བསྟན་ནས། ང་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡིན། འདི་ཨཱ་མི་དེ་བ་ཡིན། ཁྱེད་གཉིས་བྲེད་མི་དགོས་ཅེས་གསུངས་པ་དང་། ཁོང་གཉིས་ན་རེ་འོ་ན་ཁྱེད་སེམས་ཅན་དེ་ཙམ་གྱི་སྲོག་བཅད་ནས་ཅི་བྱེད། ཨཱརྱ་པ་ལོ་ནི་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡིན་པ་ལ་ཟེར་བས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཞལ་ནས་ངས་རྒྱལ་སྲིད་བཟུང་ནས། སེམས་ཅན་ལ་བ་སྤུའི་རྩེ་མོ་ཙམ་ཞིག་གིའང་གནོད་པ་སྐྱེལ་མ་མྱོང་སྟེ། ངའི་གདུལ་བྱ་འདི་རྣམས་ཞི་བས་མ་ཐུལ་པས། ཐབས་དྲག་པོའི་སྒོ་ནས་སྤྲུལ་པའི་མི་ལ་ཆད་པ་བཅད་ནས། དགེ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་པ་ཡིན། ཉིན་པར་བཅད་པ་ཡང་། ནུབ་མོར་སོང་ཙ་ན་མི་གཅིག་ལ་ཡང་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པ་མེད་གསུང་ངོ་། །དེ་ཁྱེད་གཉིས་དངོས་གྲུབ་ཅི་འདོད་གསུང་བས།

When the king learnt of their decision, he sent a minister riding a black-faced horse, ‘Summon to me those who look dissimilar to us, down in the plains of Dan ʼbag, with their shaven heads and two layers of square yellow robes.’

The minister left to fetch the two. The pair thought, ‘Now we are both going to be punished,’ and they became frightened.

Then, led by the minister, they went and met the king at the western gate of Ne’u kha. He asked them in Khotanese, ‘Why have you two come here?’ The pair told him their story and the king said, ‘Do you wish to see the face of Ārya pa lo (Avalokiteśvara)?’ They asked to see him. The king led the pair to the sandy island of Ne’u chung, near Lhasa, and after unravelling the turban on his head he showed them Ārya pa lo. ‘I am king of Tibet, this is A mi de ba (Amitābha). You two need not be afraid,’ he said. The pair said: ‘But you have ended the life of so many sentient beings. Why have you done this? Ārya pa lo is very compassionate.’ The king replied: ‘I rule the kingdom. I have not caused harm to even one hair of the head of a sentient being. My trainees could not be controlled by peaceful means; so I have [had to] use aggressive methods to punish emanated people. It is the law of the ten virtues. Although adjudicated by day, when night has passed not a single person has been punished. Now, what supernatural powers (dngos grub) do you two want?’

ལུས་སེམས་དུབ་པ་དང་། དེ་གཉིས་སྐྱེངས་ནས་རང་གི་ཡུལ་དུ་མཆི་འཚལ་བར་ཞུ་ཟེར་རོ། །རྒྱལ་པོའི་དེ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་རྒྱགས་ཕྱེའི་སྣོད་བྱེ་མས་འགེངས་སུ་བཅུག་ནས་སྔས་སུ་ཆུག་པ། རང་རང་གི་ཡུལ་ཡིད་ལ་བགྱིས་ལ་ཉོལ་ཅིག་གསུང་ནས་དེ་ལྟར་དུ་བྱས་ཉལ་པས་ནང་བར་རང་གི་ཡུལ་གྱི་སྒོ་རྩ་ལ་འགྲམ་པ་ལ་ཉི་མ་ཕོག་ནས་བྱེ་མ་རྐྱལ་བུ་གང་པོ་གཉིས་ཀྱང་གསེར་དུ་སོང་ནས་འདུག་གོ །དེ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་ཚེ་དེ་ལ་དངོས་གྲུབ་མ་ཐོབ་ཀྱང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་དང་ཞལ་མཇལ་བས། སྐྱེ་བ་དེའི་འོག་ཏུ་འཕགས་པ་དགྲ་བཅོམ་པ་བརྒྱན་མེད་རེ་ཐོབ་པོ།

Being weary, physically and mentally, the embarrassed pair said, ‘Please can we go to our country?’ The king filled their tsampa bags with flour and placed them by their pillows. He said, ‘Lie down and imagine your country.’ They did so, and slept. The next morning they were on the slope of the gateway to their country. As the sun reached them, both their tsampa bags were turned entirely to gold. Although the pair did not obtain supernatural powers in this life, because they had met the king, in a subsequent life they attained the level of ’phags pa dgra bcom pa brgyan med (unadorned arhats).4

The text continues by referring to the Khotan Prophecy (Li lung bstan).

Footnotes:

- The four texts are earlier listed as: Bhi ma la mu ti dpal spang skong phyag brgya ba, mDo za ma tog bkod pa, kLu’i dpal spong skong phyag rgya ba, and Mi dge ba bcu la log. ↩

- Or, read skyid for skyed: ‘you were happy’. ↩

- gDung seb. See Sorensen (1994: 366) ↩

- The sense is that they have been ‘totally liberated from all disturbing emotions’ (Jamgön Mipham Rinpoche 2000: 141). ↩