One Hundred Thousand Pronouncements on Ma ni

Ma ṇi bka’ ʼbum

Introduction

This text contains a heterogeneous collection of ‘treasure’ works (gter ma), largely relating to the deity of Great Compassion (Mahākaruṇā). The mantra associated with the deity is known as the Ma ṇi mantra, hence the title of the collection. The historical sections include biographical material on the emperor Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po), who is said to be an emanation of the deity Tukjé Chenpo (Thugs rje chen po, known also as Chenrezig, sPyan ras gzigs).

The miscellany of texts included in the several manuscript and published versions of the collection vary. Traditionally, the author is said to be Songtsen Gampo himself, whose writings where rediscovered as treasure texts in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Current scholarship suggests that the primary authors of the rediscovered texts were Druptob Ngodrup (Grub thob dngos grub) in the twelfth century, Nyangrel Nyima Ozer (Nyang ral nyi ma ’od zer) (1136–1204), and Jetsun Shakya Zangpo (rJe btsun shakya bzang po) in the thirteenth century.

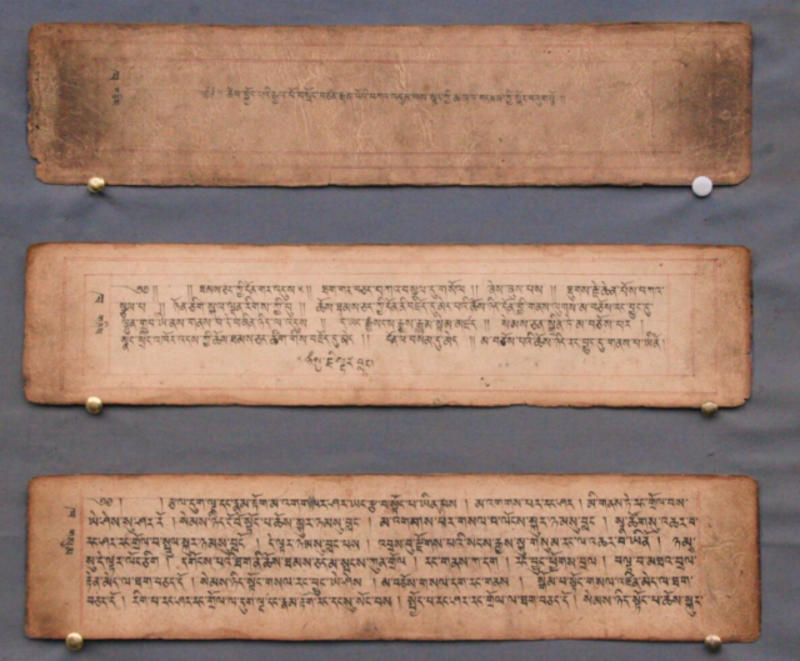

The version used for the extracts reproduced here is from a xylograph, known as the Punakha version (from sPu na kha monastery in Bhutan). The xylograph blocks are likely to have been carved in the late seventeenth century (Kapstein 1992: 163). A reproduction of the xylograph print was published in 1975 by Trayang and Jamyang Samten, and presented in two volumes. In this version, volume 1 contains mythical-historical works, and volume 2 consists of texts on Great Compassion meditation and ritual practices.

The sections of interest regarding Tibetan law are contained in volume 1, part A, sections 2 and 3, which contain different (but similar) accounts of the life of Songtsen Gampo.

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

Ma ṇi bkaʾ ʾbum: A Collection of Rediscovered Teachings Focussing upon the Tutelary Deity Avalokiteśvara (Mahākaruṇika), reproduced from a print from the no longer extant Spuṇs-thaṇ blocks. 1975. Trayang and Jamyang Samten (eds), New Delhi. BDRC: W19225.

Also used for occasional Tibetan spelling variations: Chos rgyal srong btsan sgam po. 2011. Ma ṇi bka’ ʼbum. rDo sbis tshe ring rdo rje (ed.) Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang.

References

Aris, Michael. 1979. Bhutan: The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. pp. 8–24.

Kapstein, Matthew. 1992. Remarks on the Maṇi bKa’ ʼbum and the Cult of Avalokiteśvara in Tibet. In S.D. Goodman and R.M. Davidson (eds), Tibetan Buddhism: Reason and Revelation. Albany: State University of New York.

Macdonald, Ariane. 1968. Histoire et philologie tibétaines. In the Annuaire 1968–1969 of the École pratique des hautes études. 4e section, Sciences historiques et philologiques, pp. 527–35.

Vostrikov, A.I. (H.C. Gupta, trans.) 1994. Tibetan Historical Literature. Richmond (Surrey): Curzon Press, pp. 52–57.

Outline

The Tibetan passages follow the 1975 edition, which reproduces a xylograph taken from blocks kept at Punakha (Spungs thang), including its page numbers. The headings reflect the section descriptions in the text itself, with added numbering. Occasional alternative spellings, placed in brackets, are derived from the 2011 Beijing edition.

Volume 1

Part A: The first volume from the writings of the protector of religion, King Songtsen Gampo:

a prayer to the lineage lamas, the history, and so forth.

1 The great history (lo rgyus chen mo), named the personal instructions of the 1,000 Buddhas

(36 chapters and an epilogue, pp. 1–194)

2 On the deeds and life story of the dharma-protector King Songtsen Gampo

(28 chapters, pp. 194–366)

3 The twenty-one deeds of the king

(21 chapters and an epilogue, pp. 366–423)

Part B: The dharma cycle of rituals of great compassion (mahākaruṇā) created by the dharma-protector King Songtsen Gampo

(pp. 423–625)

Volume 2

Part A: The second volume from the writings of the protector of religion, King Songtsen Gampo: his personal instructions (pp. 1–617)

Part B: Personal instructions from the protector of religion, King Songtsen Gampo: realization of sublime Namké Gyalpo (’Phags pa Nam kha’i rgyal po) and some other pieces (pp. 619–711)

Extracts

Volume 1

Part A

Section 2: On the deeds and life story of the dharma-protector King Songtsen Gampo

Chapter 1: Enhancing the people of Tibet, descended from the monkey and the rock ogress.

Chapter 2: The inception of the true doctrine in Tibet.

Chapter 3: Entering the womb.

Chapter 4: Birth.

Chapter 5: The invention of a Tibetan script and translation of the doctrine.

Chapter 6: The empowerment and the emanation of pure lands.

Chapter 7: Establishing the law.

Chapter 8: Inviting and bringing the tutelary deity.

Chapter 9: The arrival of supports for body, speech, and mind.

Chapter 10: The arrival of the tutelary deity, self-born in the Tibetan region.

Chapter 11: The invitation of Princess Tritsun (Khri btsun), emanation of the goddess Lhamo Tronyerchen (Khro gnyer can), who comes to Tibet and meets the king.

Chapter 12: Nepali Queen Tritsun erects Marpori (dMar po ri).

Chapter 13: The invitation of the Chinese Queen Kong jo (Kong jo)1 to Tibet and how the ministers compete in trickery.

Chapter 14: The building of temples, which fully pacify the four parts (of central Tibet) and the border regions.

Chapter 15: The building of temples of the tutelary deity and enforcement of the law.

Chapter 16: Dharma translation and treasure (gter ma) concealment.

Chapters 17—28: Earlier incarnations of King Songtsen Gampo.

Chapter 7: Establishing the Law.

Songtsen Gampo becomes king at the age of thirteen, with his parents’ approval, and establishes his rule in accordance with Buddhist principles and blessings.

[1975, p. 204, l.6]

།།དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོས་བོད་ཁམས་ཆོས་ལ་བཙུད་པའི་ཕྱིར་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་མདོ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་ཏེ། སྔོན་གྱི་དུས་ན་བོད་ཀྱི་ཡུལ་འདིར་རྒྱལ་ཕྲན་བཅུ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་པ་མི་དགེ་བར་སོང་ནས་བོད་ཡུལ་དུ་བདེ་བ་མ་བྱུང་བ་ཡིན་ནོ། །ང་ནི་ཆོས་སྐྱོང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡིན་པས་བོད་ཁམས་ཐམས་ཅད་དགེ་བ་ལ་དགོད་པར་བྱའོ། །ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མེད་ན་མི་དགེ་བའི་དབང་དུ་གྱུར་ནས་སྡུག་བསྔལ་གྱི་རྒྱུ་འབའ་ཞིག་ལ་སྤྱད་པས། འབྲས་བུ་ངན་སོང་གསུམ་དུ་སྐྱེ་བར་འགྱུར་རོ། །མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ནི་ལུས་ཀྱི་སྒོ་ནས་ཕ་རོལ་པོའི་སྲོག་གཅོད་པ་དང་། མ་བྱིན་པར་ལེན་པ་དང་། འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱོད་པ་དང་གསུམ་མོ། །ངག་གི་སྒོ་ནས་བརྫུན་༼རྫུན་༽ དང་། ཕྲ་མ་དང་། ཚིག་རྩུབ་དང་། །ངག་འཁྱལ་དང་བཞིའོ། །ཡིད་ཀྱི་སྒོ་ནས་བརྣབ་སེམས་དང་། གནོན་སེམས་དང་། ལོག་ལྟ་དང་གསུམ་མོ། །མདོར་ན་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་པོ་དེ་ངའི་བཀའ་དང་འཁོར་དུ་གཏོགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་སྤོངས་ཤིག །བསད་ན་སྟོང་འདོད་དོ། །རྐུས་ན་རྒྱལ་འཇལ་དངོས་དགུ་འདོད་དོ། །འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱད་ན་རིན་འདོད་དོ། །བརྫུན་སྨྲས་ན་མནའ་སྒོག་གོ །ཞེས་རྩ་བ་བཞིའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

So, in order to guide the Tibetan kingdom towards the doctrine (chos), the king established laws based on the sutra of the ten virtues. He explained that, ‘In former times, when the twelve minor kings created law here in Tibet, non-virtuous activities were carried out and there was no happiness. But since I am a king who protects the doctrine, all areas of Tibet will be established in virtue. When there is no religious law, people are influenced by non-virtue and behave in ways that cause suffering, and as a result they are reborn in the three lower realms. As for the non-virtues, in physical terms, they are threefold: taking others’ lives, taking what is not given, and sexual misconduct. In terms of speech, they are fourfold: lying, slander, harsh words, and gossip. In terms of the mind, they are three: covetousness, maliciousness, and wrong views. In brief, the ten non-virtues ought to be avoided by those under my dominion and in my realm. If someone kills, compensation is required. If someone steals, nine-fold compensation must be paid. If someone engages in sexual misconduct, a payment is required. If someone lies, he should take an oath. In this way, the four root laws are established.

[1975, p. 205, l.5]

།གཞན་ཡང་ངའི་བཀའ་འབངས་སུ་གཏོགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་ལྷ་དཀོན་མཆོག་གསུམ་ལ་དད་པ་དང་གུས་པ་བསྐྱེད་བར་བྱའོ། །དམ་པའི་ལྷ་ཆོས་བཙལ་ཞིང་བསྒྲུབ་པར་བྱའོ། །ཕ་དང་མ་ལ་དྲིན་གྱི་ལན་ལྡོན་པར་བྱའོ། །ཡོན་ཏན་ཅན་ལ་ཞེ་མཐོང་ཆེ་བར་བྱའོ། །རིགས་མཐོ་བ་དང་རྒན་པ་ལ་བཀུར་སྟི་ཆེན་པོ་༼པོར་༽ བྱའོ། །ཉེ་དུ་དང་མཛའ་བཤེས་ལ་གཞུང་བཟང་བར་བྱའོ། ཡུལ་མི་ཁྱིམ་མཛེས་༼མཚེས་༽ ལ་ཕན་གདགས་པར་བྱའོ། །བཀའ་དྲང་ཞིང་སེམས་ཆུང་བར་བྱའོ། །ཡ་རབས་ཀྱི་རྗེས་སྙག་༼སྙེག་༽ཅིང་ཕྱི་ཐག་རིང་བར་བྱའོ། །ཟས་ནོར་ལ་ཚོད་ཟིན་པར་བྱའོ། །སྔ་དྲིན་ཅན་གྱི་ཡི་མི་བཅད་པར་བྱའོ། །བུ་ལོན་དུས་སུ་འཇལ་བར་བྱ་ཞིང་བྲེ་སྲང་ལ་གཡོ་སྒྱུ་མེད་པར་བྱའོ། །ཀུན་ལ་སྙོམས་ཤིང་ཕྲ་དོག་མེད་པར་བྱའོ། །གྲོགས་ཀྱི་ནང་དུ་ངན་པའི་ངག་ལ་མི་ཉན་པར་རང་ཚུགས་འཛིན་པར་བྱའོ། །ངག་འཇམ་ཞིང་སྨྲ་བ་ཉུང་བར་བྱའོ། །ཐེག་པ་ཆེ་ཞིང་བློ་ཁོག་ཡངས་པར་བྱའོ། ཞེས་བཀའ་སྩལ་ཞིང་། དེ་ལྟར་མི་ཆོས་གཙང་མ་བཅུ་དྲུག་གིས་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་གཞི་གཟུང་ནས། བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ནན་ཏན་ཆེར་མཛད་དོ། །ཁྲིམས་བཅས་པའི་མཛད་པའོ།།

Furthermore, the subjects under my dominion ought to generate faith in the Three Divine Jewels. They ought to practise and accomplish the true doctrine. They ought to repay the kindness of their parents. They ought to respect those who have (good) qualities. They ought to respect the upper classes and elders. They ought to be honest with relatives and friends. They ought to give help to their fellow countrymen and neighbours. They ought to talk straightforwardly and with humility. They ought to follow the nobility assiduously. They ought to be careful about food and wealth. They ought not to cut themselves off from those who have previously been kind. Debts ought to be repaid on time and there should be no deception with bre and srang measures. They ought to act fairly towards everyone and without jealousy. They should not listen to the bad things that close friends say, but maintain their own judgement. They should speak gently and discreetly. They ought to act with forbearance and magnanimity. In this way, the sixteen pure human norms will establish the basis of the law.’ He took great pains to proclaim the law (bka’ khrims). The laws were established.

Chapter 11: The invitation of Princess Tritsun, emanation of the goddess Lhamo Tronyerchen (Khro gnyer can), who comes to Tibet and meets the king

King Songtsen Gampo sends his minister, Gar (mGar), to Nepal to negotiate with King Ozer Gocha (ʼOd zer go cha) for the hand of Princess Tritsun in marriage.

[1975, p. 224, l.2]

བལ་པོའི་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཁྲེལ་རྒོད་བྱས་ཏེ་ལན་ཅི་ཡང་མི་སྨྲ་བར་མིག་མི་འབྱེད་པར་བཙུམས་ནས་དེ་ནས་རིང་པོར་བསམས་ཏེ། ཁྱེད་ཀྱིས་ངའི་གཉེན་ཟླ་མི་འོང་ཁྱེད་པས་ང་བཟང་ལ་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་ཆགས། ཁྱེད་མཐའ་ཁོབ་༼འཁོབ་༽ ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ཁྲིམས་མེད། ཁྱེད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་སུ་ཁྲིམས་འཆའ་ནུས་ན་ངས་བུ་མོ་བྱིན་གྱིས། དེ་མིན་ན་མི་སྟེར་གྱིས་ལ་དེའི་ལོན་༼ལན་༽ ཁྱེད་རང་གི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་དྲིས་ལ་ཁྱེར་ཤོག་ཟེར་བས། དེ་ཙ་ན་སྒྲོམ་བུ་འདི་ཕུལ་ཞིག་གསུང་བ་དྲན་ནས།

The King of Nepal laughed scornfully. Without giving any answer, he closed his eyes and thought for a long time. He said, ‘You will not become a relative of mine. I am superior to you, since I have created laws of the ten virtues. You are king of a barbarous region, without any law. If you are able to establish law in your kingdom, I will grant you my daughter. If not, I will not let her be given. Relay that to your king and ask for an answer’. Then [the minister] remembered that he had been told, ‘Offer this box!’

The minister Gar offers the bejewelled golden box to the king.

[1975, p. 224, l.6]

དེར་རྒྱལ་པོས་སྒྲོམ་བུ་དེའི་ཁ་ཕྱེ་བས་དེའི་ནང་ནས་བལ་པོའི་ཡི་གེ་བྱུང་སྟེ་བཀླགས་པས། ཁྱེད་ལྷོ་བལ་གྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ཁྲིམས་ཆགས། ངེད་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ཁྲིམས་མེད་དེ། རྒྱལ་པོ་ཁྱེད་ཁྲིམས་ལ་དགེས་ཤིང་ལྷ་གཅིག་ཁྲི་བཙུན་བཀས་གནང་ན། ངས་ཉི་མ་གཅིག་ལ་སྐུ་ལུས་ཀྱི་བཀོད་པ་ལྔ་སྟོང་དུ་སྤྲུལ་ནས། བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ཐམས་ཅད་དུ་སྤྲུལ་པས་དགེ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་ལ་བཞག་གི༼གིས།༽ དེ་ངོ་མཚར་རམ་བྱ་བ་བྲིས་ནས་བྱུང་བས།

Then the king opened the box. In it was a letter written in Nepalese, which he read. It said: ‘You, King of Nepal in the south, have created laws. I, King of Tibet, have no law. As you, King, are pleased with the law, if you order the despatch of Princess Khri btsun, in one day I will manifest five thousand physical bodies. They will manifest in the whole kingdom of snowy Tibet: will this (means of) establishing the laws of the ten virtues not be wonderful?’

The King of Nepal, now referred to as Ratna Deva, (Ratna dhe wa) agrees to the marriage and then addresses his daughter Princess Tritsun about her impending journey to Tibet.

[1975, p.229, l.3]

།དམ་ཆོས་མེད་ཀྱང་རྒྱལ་པོའི་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་གནས།

།གྲོགས་མཆེད་དགེ་འདུན་མེད་ཀྱང་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་ཡིན།

།དེ་འདྲའི་གནས་སུ་བུ་མོ་ཁྱོད་སོང་ལ།

།བདག་གི་མཆོད་གནས་ཤཱཀྱ་མུ་ནེ་ནི།

‘Although the true doctrine does not exist (there), it is a place with royal laws;

Although the Buddhist sangha does not exist, the king is an emanation.

To such a place, daughter, you will go.

The image of Shakyamuni is my object of offering’.

Chapter 13: The invitation of the Chinese Queen Kongjo (kong jo) to Tibet and how the ministers compete in trickery

Minister Gar is then sent to China to negotiate the hand of Princess Kongjo (also known as Princess Wencheng) in another marriage for King Songtsen Gampo. He is set a number of tests, which he succeeds in completing through trickery and cleverness. The Chinese king then tells his daughter that she must go to Tibet, but she objects.

[1975, p. 240, l.5]

།དེ་ལ་ཡང་མོ་ན་རེ་གཉེན་སུ་དང་ཡང་མི་འཕྲད། ཆོས་དང་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་ཀྱང་མེད། ཁྲིམས་མེད་པའི་ས་དེ་རུ་ང་མི་འགྲོ་ཟེར་རོ།

So she [the princess] said: ‘Neither will I meet with my relatives and nor are there Buddhist doctrine or material enjoyments. To that place without law, I will not go.’

Chapter 15: The founding of temples for the tutelary deity and enforcement of the law

The Queens Wencheng of China, Tritsun of Nepal, and Ruyongza (Ru yong bza’) of Zhangzhung (Zhang zhung) build temples in Tibet.

[1975, p. 277, l.1]

སྤྲུལ་པ་སྟོང་ཐམ་པས་སྡིག་པ་བྱེད་པ་རྣམས་ལ་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པའི་ཕྱིར་དུ་ཁྲི་དང་ཁྲིའུའི་སྟེང་དུ་འདུག་སྟེ། གཤེད་མ་སྣ་ཚོགས་ཀྱིས་བསྐོར་ནས། ཉེས་པའི་ལས་བྱེད་པའི་སྐྱེ་བོ་དག་གི་མགོ་འབྲེག་པ་དང་། མིག་འབྱིན་པ་དང་། པགས་པ་ཤུ་༼བཤུ་༽ བ་དང་། མེ་ཐབ་ཏུ་འཛུད་པ་དང་། སོ་དོང་དུ་སྦེད་པ་དང་། ཆུར་བསྐྱུར་བ་དང་། རླུང་ལ་འཕྱར་བ་དང་། དབྱུག་པ་བརྡེག་པ་ལ་སོགས་པ་ཆད་པ་རྣམ་པ་སྣ་ཚོགས་ཀྱིས་སྡིགས་པར་བྱེད་དོ།

In order for a thousand emanations to punish the sinful, [the queens] sat on thrones and chairs, surrounded by various executioners. People who had done evil deeds had their heads cut off, their eyes were pulled out, their skin was flayed, they were thrown into fires, buried in holes, left immersed in water, lifted into the air, beaten with sticks, and so on. With punishments of [these] various kinds, people were intimidated.

[1975, p. 277, l. 4]

།དེའི་ཚེ་ལི་ཡུལ་གྱི་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་ལོ་བཅུ་གཉིས་སུ་འཕགས་པ་འཇམ་དཔལ་བསྒྲུབས་པས་མ་འགྲུབ་ནས། ནུབ་ཅིག་ཚེ་འཕགས་པ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་རེ་ཆུང་ན་ཞེས་སྨྲེ་སྔགས་མང་དུ་བཏོན་པས་འཇམ་དཔལ་གྱིས་རྨི་ལམ་དུ། ང་དང་ཁྱེད་ལ་ལས་འབྲེལ་མེད་ཅིང་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་དང་ལས་འབྲེལ་ཡོད་པས། དེ་བོད་ཡུལ་དུ་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ་ཞེས་བྱ་བར་སྤྲུལ་ནས། འགྲོ་དོན་བྱེད་ཀྱིན་ཡོད་པས་དེར་སོང་ཞིག་ཅེས་ལུང་བསྟན་ཏོ། །དེ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་བོད་ཡུལ་གང་ན་ཡོད་མི་ཤེས་ཀྱང་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ་ཡིད་ལ་བྱེད་ཅིང་འོངས་པས་བོད་དུ་སླེབ་བ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ཁྲིམས་འཆའ་བ་དང་ཐུག་སྟེ། མགོ་བྲེགས་པ་ནི་ས་ཕུང་ཙམ། ཁྲག་འབབ་པ་ནི་ཆུ་ཀླུང་ཙམ་མཐོང་བས་བྲེད་ཅིང་སྔངས་ཏེ། སྤྲུལ་པ་ནི་ཅིའི་སྤྲུལ་པ། སྡིག་སྤྱོད་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཞིག་འདུག་པ་ཞེས་སྨྲ་ཞིང་ཕྱིར་བྲོས་སོ། །རྒྱལ་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་ཕྱིར་ལོག་པར་མཁྱེན་ཏེ། འགུགས་མི་བཏང་ནས་བཀུག་པ་དང་། སླར་ཡང་ཤིན་ཏུ་སྐྲག་པར་གྱུར་ཏོ། །དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོས་ལི་ཡུལ་གྱི་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་པོ་ལ་ལིའི་སྐད་དུ་དངོས་གྲུབ་ཅི་འདོད་དྲིས་པས། རང་ཡུལ་དུ་ད་ལྟ་རང་ལ་སླེབ་པར་འདོད་དོ་ཞེས་སྨྲས་སོ། །རྒྱལ་པོས་དེ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་སྣོད་བྱེ་མས་འགེངས་སུ་བཅུག་ནས་འཕང་དུ་བཅུག་སྟེ། ཡུལ་ཡིད་ལ་གྱིས་ལ་ཉོལ་ཅིག་ཅེས་གསུངས་སོ། །དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་མ་ཐག་ཏུ་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་པོ་ཡུལ་དུ་སླེབ་ནས་བྱེ་མ་གསེར་དུ་སོང་སྟེ་འདུག་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་མོས་གུས་ཐུན་མོང་མ་ཡིན་པ་སྐྱེས་པའི་མཐུས་སྐྱེ་བ་དེ་ཉིད་དུ་ཟག་པ་ཟད་པའི་དགྲ་བཅོམ་པར་གྱུར་ཏོ། །ཐུགས་དམ་གྱི་ལྷ་ཁང་བཞེངས་ཤིང་ཁྲིམས་མནན་པའི་མཛད་པའོ།།

At that time, in Li yul [Khotan], there were two novice monks who had venerated the exalted ’Jam dpal [Mañjuśrī] for twelve years, without success. One night they decided there was little hope of the exalted one’s compassion because they had already chanted many mantras. [But] in a dream, ’Jam dpal told them: ‘You and I do not have a karmic connection, but you have a karmic connection with Thugs rje chen po [Mahākaruṇā]. He has manifested in Tibet, where he is called King Songtsen Gampo. Since he is acting for the benefit of sentient beings, you should go there.’ Although the two did not know where Tibet was, they left, keeping King Songtsen Gampo in their minds. They arrived in Tibet and found the king’s law being enforced. Severed heads were piled on the ground. Seeing blood flowing like a stream, they were frightened and panicked. They said: ‘What kind of emanation is this? He is a sinful king,’ and they fled. The king realized the two were turning back. Not allowing them to run away, he summoned them, and they became even more frightened. Then the king, using the language of Li yul, asked the two novices what spiritual attainments they wished for. They asked to return to their own country. The king gave the pair a container full of sand, and sent them off, saying, ‘Lie down and think of your homeland.’ As soon as they did so, the two novices arrived in their country and found that the sand had turned to gold. They became extraordinarily devoted to the king and became dgra bcom pa (‘arhats’ who had exhausted their defilements).

That was the construction of temples for the tutelary deities and the enforcement of the law.

Section 3: The Twenty-One Deeds of the King

Chapter 1: The speech of Thugs rje chen po (Mahākaruṇā) and the self-arising sutras of the holy dharma first coming to Tibet.

Chapter 2: The emanation prince enters the womb of the queen.

Chapter 3: The emanation prince’s birth.

Chapter 4: Training in writing, the Buddhist doctrine, mastery of meditation.

Chapter 5: Empowerment and emanation of pure lands.

Chapter 6: Establishing the laws of the ten virtues and founding Tibet’s religious law.

Chapter 7: Invitation to the naturally-occurring deity of Great Compassion (Mahākaruṇā).

Chapter 8: The three self-arising statues which liberate people from the suffering of fear.

Chapter 9: The emanated king’s supports of body, speech, and mind, and his miraculous prophecy.

Chapter 10: Marriage to Princess Tritsun, emanation of the goddess Lhamo Tronyerma (Khro gnyer ma).

Chapter 11: The invitation of Princess Kongjo, and their marriage.

Chapter 12: The activities of Kongjo demonstrating geomancy.

Chapter 13: The creation of temples in order to suppress the limbs of the negative geomantic demoness.

Chapter 14: The creation of a self-arising statue.

Chapter 15: The building of the temple.

Chapter 16: The establishment of the laws.

Chapter 17: Establishing Tibet and Khams in happiness and consecrating temples.

Chapter 18: The emanated king establishes all Tibet and Khams in the dharma.

Chapter 19: The concealment of treasures.

Chapter 20: How the teachings of Great Compassion arise and are hidden as treasure.

Chapter 21: The emanated king spreads the teaching and demonstrates his body subsiding.

Epilogue

Chapter 5: Empowerment and emanation of pure lands

Songtsen Gampo becomes king of Tibet as a teenager, with his parents’ approval. Several deities manifest to empower him.

[1975, p. 374, l. 1]

ད་ནས་དགུང་ལོ་བཅུ་གསུམ་ན། སྤྲུལ་པའི་རྒྱལ་བུའི་ཐུགས་དགོངས་ལ། ད་ནི་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་འདི་ཆོས་ཀྱིས་འདུལ་དགོས་པ་ལ་འདིར་སྐྱེས་པའི་མི་རྣམས། ཕ་སྤྲེའུ་དང་མ་བྲག་སྲིན་གྱི་བུ་དུད་འགྲོའི་རིགས་སུ་སོང་བས། ཞི་བས་མི་ཐུལ་ཏེ། ཐབས་དྲག་པོས་ནན་གྱིས་ཆད་པས་བཅད་ནས་འདུལ་དགོས་པར་འདུག །དེ་ལ་དབང་ཆེ་བ་ཞིག་དགོས་པས། བདག་རྒྱལ་སར་ཕྱུང་ནས་དབང་བསྐུར་བར་དགོངས་ནས།

At the age of thirteen, the emanation prince formed a resolution: ‘Now, this snowy kingdom must be civilized through the dharma. Since people born here are children of the father monkey and mother rock ogress, belonging to the class of animals, they are uncivilized; they must be tamed by being punished severely, using harsh methods. For that, a very powerful man is needed. After I have gone to the capital, I will be empowered.’

Chapter 6: Establishing the laws of the ten virtues and founding Tibet’s religious law

King Songtsen Gampo establishes the laws of Tibet on the basis of Buddhist morality.

[1975, p. 375, l. 6]

དེ་ནས་སྤྲུལ་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོས། བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་སེམས་ཅན་ཆོས་ལ་གཟུད་པའི་ཕྱིར། དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་མདོ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་ཏེ། དེ་ཡང་སྔོན་གྱི་དུས་སུ་ཡང་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མེད་པས། བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ཕྲན་བཅུ་གཉིས་ཕྱིར་འཁྱར། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་སྡིག་ཁྲིམས་སུ་སོང་བ་ཡིན་བས། བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་སུ་བདེ་བ་མ་བྱུང་བ་ཡིན་ནོ། །ང་ནི་ཆོས་སྐྱོང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡིན་པས། བོད་ཐམས་ཅད་ཆོས་དང་དགེ་བ་ལ་འགོད་པ་ཡིན་ཏེ། གལ་ཏེ་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མེད་ན་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་སྤྱད་པས་ངན་སོང་གསུམ་དུ་སྡུག་བསྔལ་ཐར་བ་མེད་པ་མྱོང་བར་འགྱུར་རོ།

Then the royal emanation, in order to cause the sentient beings of snowy Tibet to accept the Buddhist doctrine, made laws based on the sutra of the ten virtues. [The king declared] ‘Since in former times there was no religious law at all, the twelve lesser kingdoms were disorganized and there were sinful traditions of royal law. In the kingdom of Tibet there was no happiness. Since I am a king who protects the doctrine, the whole of Tibet will be secure in the doctrine and in virtue. If there is no religious law, those who perform the ten non-virtues will experience the non-liberating suffering of the three lower realms.’

[1975, p.376 l. 3]

།དེ་ཡང་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལས། ལུས་ཀྱི་ལས་གསུམ་ནི། སེམས་ཅན་གྱི་སྲོག་གཅོད་པ་དང་། གཞན་གྱི་ནོར་ལ་རྐུ་བ་དང་། གཞན་གྱི་བུད་མེད་བདག་པོ་ཅན་ལ་སྤྱོད་པའོ། །ངག་གི་མི་དགེ་བ་བཞི་ནི། གནོད་པ་ཅན་གྱི་བརྫུན་སྨྲ་བ། ཕ་རོལ་ལ་དབྱེན་སེམས་ཀྱི་ཕྲ་མ། རྩུབ་མོ་སྨྲ་འདོད་པ། ངག་ཀྱལ་པས་གཞན་གྱི་མཚང་འདྲུ་བའོ། །ཡིད་ཀྱི་མི་དགེ་བ་གསུམ་ལ། གནོད་སེམས་ཞེ་ལ་འཆང་བ། བརྣབ་སེམས་གཞན་ལ་མེད་པར་རང་ལ་ཡོད་ན་དགའ་བ། ལོག་ལྟས་ཆོས་མི་བདེན་སྙམ་པ་སྟེ། ལུས་ངག་ཡིད་གསུམ་གྱི་མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་པོ་དེ། ངའི་བཀའ་དང་འཁོར་དུ་གཏོགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་སྤོངས་ཤིག །བོད་སྤྱི་མཐུན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་སུ་ཁྲིམས་རྩ་བ་བཞི་བཅས་སོ། །འཐབས་ནས་མ་བསད་ཅིག །མི་སྟོང་འདོད་དོ། །ཕན་ཚུན་མ་རྐུ་ཞིག །རྐུས་ན་རྐུས་ཆལ་༼འཇལ་༽ འདོད་དོ། །འདོད་ལོག་མ་བྱེད་ཅིག །བྱས་ན་སྨད་ཆལ་འདོད་དོ། །བརྫུན་མ་སྨྲ་ཞིག་སྨྲས་ན་མནའ་སྒོག་གོ །ཞེས་བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་ཐམས་ཅད་དུ་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་དང་བཀའ་ནན་ཆེར་མཛད་དོ། །དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་ལ་བཅས་ནས། བོད་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་བཀོད་པར་མཛད་པའི་ལེའུ་སྟེ་དྲུག་པའོ།།

The ten non-virtues comprise three physical ones: killing sentient beings, stealing others’ wealth, and seizing others’ women. The four non-virtues of speech are: speaking harmful lies, divisive speech with an attitude of antagonism towards others, enjoying saying abusive things, and exposing the faults of others through gossip. The mental non-virtues are threefold: harbouring a harmful attitude, the miserliness that delights in what one has and others do not have, and harbouring wrong views leading to contemplation of untrue doctrine. These are the ten non-virtues of the trio of body, speech, and mind, and I command (that) those within my dominions should reject them. The four root laws have been established throughout the royal kingdom of Tibet. Do not kill through fighting; (if you do), blood money will be due. Do not steal from one another; if you steal, compensation for theft will be due. Do not engage in sexual misconduct; if you do, compensation is due. Do not tell lies; if you do, you must swear an oath. In this way, I have made the laws and severe edicts in snowy Tibet.’

After making the laws of the ten virtues, the religious law was established in Tibet. The sixth chapter.

Chapter 16: The establishment of the laws

[1975, p. 407, l.1]

དེ་ནས་སྤྲུལ་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་དེས། དང་པོ་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས། བར་མ་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་ནས་ལྷ་ས་རྩིག་པའི་དུས་སུ་སྤྲུལ་པའི་མི་ལ་ཆད་པ་བཅད་ནས། ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་ལྕགས་རིའི་གད་ཁ་ན། མགོ་བོ་བཅད་པ་དང་། རྐང་ལག་བྲེགས་པ་དང་། མིག་འབྱིན་པ་དང་། ཆད་པ་གཅོད་པ་རྒྱུན་མ་ཆད་པར་སྤྲུལ་ནས། བོད་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་མི་རྣམས་ཕ་སྤྲེའུ་དང་མ་བྲག་སྲིན་ཡིན་པས་གདུལ་བར་དཀའ་ཞིང་ཆོས་ལ་གཟུད་པར་དཀའ་བས། བསྡིགས་ཤིང་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་བསྲུངས་པ་ལས།

After that, the emanation king made laws of the ten virtues. Later, he made the royal law, and at the time of the building of Lhasa, punishments were meted out to emanated people. By a cliff on the western side of lCags ri, heads were cut off, arms and legs were severed, eyes were gouged out, and the execution of punishments was continuously manifested. Since the people of snowy Tibet were the progeny of a father monkey and mother rock ogress, they were hard to control and it was difficult to guide them to the doctrine. So he intimidated them, to protect the religious law.

[1975, p. 407, l.3]

དེའི་ཚེ་དེའི་དུས་སུ་ལི་ཡུལ་དུ་དགེ་ཚུལ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས། ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་བསྒྲུབས་པས་རྨི་ལམ་དུ་མི་དཀར་པོ་ཞིག་ན་རེ། ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་ནི་བོད་ཡུལ་དབུས་ན་ད་ལྟ་རྒྱལ་པོར་སྤྲུལ་ནས། ལྷ་ཁང་བརྒྱ་རྩ་བརྒྱད་རྩིག་གིན་ཡོད་ཀྱིས་དེར་སོང་ལ་ཞལ་ལྟོས་ཟེར་བ་གཉིས་ཀ་ལ་རྨིས་ནས། དེ་ནས་ནང་པར་དཀའ་སྤྱད་བྱས་ནས་བོད་དུ་འོངས་པས་བོད་དུ་སླེབ་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་གང་ན་བཞུགས་དྲིས་ཤིང་ཡར་ལུངས་སུ་ཕྱིན་ཙ་ན། དབུ་ར་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་སྤྲུལ་པའི་མི་ལ་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པའི་ར་བ་དང་། རྐང་ལག་བཅད་པ་ལ་སོགས་པ་དང་། རོའི་རྩིག་པ་ཆེན་པོ་འདུག་ནས་འདི་དག་སུས་བྱས་དྲིས་པས། རྒྱལ་པོས་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པའོ་ཟེར་རོ། །དེ་ན་རྒྱལ་པོ་མི་བཞུགས་ཏེ་ལྷ་ས་ན་ལྷ་ཁང་བརྩིག་གོ །ཞེས་ཟེར་ནས་ལྷ་སར་ཕྱིན་པ་དང་། ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་ལྕང་རའི་ཁ་ན་ཆད་པ་གཅོད་པ་རྒྱུན་མ་ཆད་པ་འདུག་ནས་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོར་མི་འདུག་བདུད་དུ་འདུག་ཟེར་ནས་ལོག་གོ

At that time in Li yul (Khotan), two novice monks had been venerating Thugs rje chen po [Mahākaruṇā]. They both dreamed that a white man said to them: ‘Thugs rje chen po has now manifested as a king in the dBus region of Tibet. He is building a hundred and eight temples and you should go there to see him.’ So, since they practised asceticism as Buddhists, they set off, and arrived in Tibet. They asked where the king was residing. When they got to Yar lung, [at the] so-called dBu ra (Enclosure of Heads), [they found] an enclosure for the punishment of emanated people and the severing of arms and legs and so forth, and a great wall of corpses. ‘Who has done this?’ they asked. They were told that these were the king’s punishments. Then, having been told that the king was not living there—he was building a temple in Lhasa—they went to Lhasa. To the west of a willow grove, punishments were being carried out continuously. They said, ‘The king is not Thugs rje chen po, he is a demon (bdud),’ and turned back.

[1975, p.408, l.1]

།དེ་རྒྱལ་པོས་མཁྱེན་ནས་བློན་པོ་ཞིག་རྟ་ནག་ཅིག་ལ་བསྐྱོན་ནས། བཙུན་པའི་ཆ་བྱད་ཅན་ལི་ཡུལ་གྱི་མི་གཉིས་ད་ལྟར་འོངས་པ་ལས་ལོག་ནས་སོང་ཡོད་པས། དེ་གཉིས་ངའི་དྲུང་དུ་ཁྲིད་ལ་ཤོག་ཅིག་ཅེས་བཀའ་བསྒོས་པས། བློན་པོས་ཕྱིར་བརྒྱུགས་ཏེ་རྒྱལ་པོའི་དྲུང་དུ་ཁྲིད་དེ་འོངས་པ་དང་། ཁྱེད་འདིར་ཅི་བྱེད་དུ་འོངས་ཞེས་དྲིས་པས། ངེད་ནི་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཡིན་ཟེར་ནས་ཞལ་ལྟ་རུ་འོངས་པས། མི་མང་པོ་ལ་ཆད་པས་བཅད་ནས་སྡིག་པའི་ལས་བྱེད་པ་ཇི་ལྟར་ལགས་དྲིས་པས། འོ་ན་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ལྟ་ན་འདིར་ཤོག་ཅིག་གསུངས་ནས། ནེའུ་བྱེ་མ་གླིང་དུ་ཕྱིན་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོས་དབུ་ཐོད་ཕུད་ནས། ཞལ་བཅུ་གཅིག་པ་དང་། ཨ་མི་དེ་བ་བསྟན་ནོ། བདག་ནི་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡིན་ཏེ། ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མ་བརྟན་གྱིས་དོགས་ནས་སྤྲུལ་བ་བྱས་ཏེ་ཐམས་ཅད་བཏུབས་༼གཏུབས་༽ པ་ཡིན། རྒྱལ་སྲིད་བཟུང་ནས་སེམས་ཅན་གཅིག་གི་བ་སྤུ་ལ་ཡང་གནོད་པ་མ་བྱས་གསུང་ངོ་། ད་དངོས་གྲུབ་ཅི་འདོད་གསུངས་པས། ད་ཡུལ་ལ་ཐག་རིང་བས་ཡུལ་དུ་སླེབ་པ་ཞིག་འདོད་ཞུས་པས། རྒྱལ་པོས་བྱེ་མ་སྤར་རེ་གཏད་ནས་གོས་ལ་འཐུམ་དུ་བཅུག་སྟེ་མིག་ཚུམས་ལ་ཡུལ་ཡིད་ལ་གྱིས་ཤིག་ཅེས་གསུངས་པས། སྐད་ཅིག་གིས་ཡུལ་དུ་ཕྱིན་ནས་འདུག །བྱེ་མ་གསེར་དུ་གྱུར་ནས་འདུག་པས་ཡིད་ཆེས་ཏེ་སྐྱེ་བ་དེ་རང་ལ་དགྲ་བཅོམ་པ་ཐོབ་བོ།

The king realized this and issued an order to a minister to set off on a black horse: ‘Two Khotanese men attired like monks have arrived, and have turned to go back. Bring those two to me.’ The minister rode off and brought them into the presence of the king. [The king] asked, ‘What have you come for?’ [They answered:] ‘We were told that the king of Tibet is Thugs rje chen po spyan ras gzigs [Mahākaruṇā Avalokiteśvara], and have come to see him. You are punishing many people; why do you carry out such bad deeds?’ [The king] said, ‘All right, if you wish to see Spyan ras gzigs, come with me.’ They went to Ne’u bye ma gling pa, where the king took off his head covering to show the eleven-faced one [Avalokiteśvara] and A mi de ba [Amitābha]. He said: ‘I am Thugs rje chen po. Since taking over the kingdom, I have not harmed so much as a hair of a single sentient being.’ Then he asked them what spiritual achievements they wished for. They said that their homeland was far away and they would like to return there. The king presented each with a handful of sand and said: ‘Put it in a package in your clothing, shut your eyes, and think of your country.’ Instantly, they were in their country and the sand had changed to gold. They acquired faith and each attained the level of dgra bcom pa (arhats who had exhausted their defilements).

Chapter 17: Establishing Tibet and Khams in happiness and consecrating temples

[1975, p. 410, l. 3]

དེ་བདུན་དང་བཅས་པར་སྤྲུལ་ནས། བོད་ཁམས་གསུམ་གླིང་དགུ་ཐམས་ཅད་དུ་བྱོན་ཏེ་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས། ལྷ་ཁང་བརྒྱ་རྩ་བརྒྱད་བརྩིགས་ཏེ་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དར་གྱི་མདུད་པ་འདྲ་བ་བཅས་ནས། བོད་ཐམས་ཅད་བདེ་བ་ལ་བཀོད་དོ། །ལྟོགས་ཕྱུག་བསྙམས་ཏེ། བྱེད་དང་། འཕར་དང་། ལྟོས་པ་མེད་པར་བྱས་ནས།

After he had manifested as one with the seven [precious accoutrements of a cakravartin king], he went to all three regions and nine sub-regions of Tibet and Khams and made the laws of the ten virtues. He built one hundred and eight temples and made the religious law, which was like a silken knot. The whole of Tibet was content. He equalized the hungry and wealthy, and made [them] active, [progress] upward, and independent.

[1975, p. 411, l. 5]

ཆོས་ལ་བཀོད་ནས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱང་བསོད་ནམས་དང་ལྡན་ཏེ་ཐར་པ་ཐོབ་པར་གཟིགས་སོ། །བོད་ཁམས་གསུམ་གླིང་དགུའི་མི་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། སྤྲུལ་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོས་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས། ལྟོགས་པ་དང་ཕྱུག་ཕ་ ༼པ་༽ བསྙམས། གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་བརྒྱ་རྩ་བརྒྱད་བཞེངས་ཏ་༼ཏེ་༽ ཤིན་ཏུ་དྲིན་ཆེ་བར་མཐོང་ངོ་། འབངས་ཕྱི་འཁོར་ནང་འཁོར་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། རྒྱལ་པོས་བོད་འབངས་ཐམས་ཅད་ལ་གསང་བསྡུས་ནས་ལྷ་ཁང་མངའ་གསོལ་མཛད་པར་ཡང་མཐོང་ངོ་། །བོད་ཁམས་བདེ་བ་ལ་བཀོད་པ་དང་། ལྷ་ཁང་མངའ་གསོལ་མཛད་པའི་ལེའུ་སྟེ་བཅུ་བདུན་པའོ།།

After the doctrine was established, everyone became virtuous and [the king] saw that they had attained liberation. The people of the three regions of Tibet and Khams and the nine sub-regions saw that the emanation King Songtsen Gampo had established the laws of ten virtues, equalized the hungry and the wealthy, and erected one hundred and eight temples. They realized that he was exceedingly kind. The subjects—his outer entourage and his inner court—also saw that the king had brought together all his Tibetan subjects spiritually, and had consecrated temples.

Establishing Tibet and Khams in happiness and consecrating temples. The seventeenth chapter.

Chapter 18: The emanated king establishes all Tibet and Kham in the dharma

In a chapter on translators and translations, after a passage on the benefits of learning to write and recite religious texts (both Bonpo and Buddhist) for the sake of the sick and the dead, the chapter ends with the following.

[1975, p.414, l. 5]

གསོན་གཤིན་གཉིས་ཀ་ལ་ཕན་པའི་ཆོས་ལ་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་པར་བཀས་གནང་། ཡི་གེ་འདྲི་བ་དང་ཀློག་པ་ཡང་གང་བྱེད་ལ་བཀའ་གནང་སྟེ། ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དར་གྱི་མདུད་པ་ལྟ་བུ་དམ་ལ་ལྷོད་པ་ལྷོད་ལ་དམ་པ། ཆོས་ཕྱོགས་སུ་ལྷོད་ལ་སྡིག་ཕྱོགས་སུ་དམ་པར་བསྡམས་སོ། །སྤྲུལ་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོས་བོད་ཁམས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཆོས་ལ་བཀོད་པར་མཛད་པའི་ལེའུ་སྟེ་བཅོ་བརྒྱད་པའོ།།

[The king] commanded that the doctrine, which benefits both the living and the dead, be practised. He gave orders that whatever else was done, literature should be written and read. The religious law, like a silken knot, loosened what was tight and tightened what was loose. It bound the religious loosely and the sinful tightly.

The emanation king establishes the whole of Tibet and Khams in the dharma. The eighteenth chapter.

Chapter 21: The emanated king spreads the teaching and demonstrates his body subsiding

[1975, p.418, l. 3]

དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཞལ་ནས། འོ་སྐོལ་ཡི་དམ་གྱི་ལྷ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་ལ་ཕྱག་བྱའོ་གསུང་ནས། གཙང་ཁང་དུ་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོའི་སྤྱན་སྔར་ཕྱག་བྱས་ནས། བློན་པོ་སྣ་ཆེན་པོ་ལ་ཞལ་བསྟན་སྤྱན་གཟིགས་ནས། ཞང་བློན་ཆེན་པོ་ཁ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་འདིར། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་སུ་བསྒྱུར་བ་ཡིན་ནོ། །ངའི་དབོན་སྲས་ལ་ཡང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དང་བསྟུན་དུ་ཆུག་ཅིག །ང་ནས་རྒྱལ་རབས་ལྔ་ནས། འཕགས་པ་འཇམ་དཔལ་གྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ། ཁྲི་སྲོང་ལྡེ་༼ལྡེའུ་༽ བཙན་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ཆོས་སྐྱོང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་འབྱུང་། དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དར་བར་བྱེད། མཐར་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱང་མངོན་པར་རྫོགས་པར་བྱང་ཆུབ་པར་འགྱུར་རོ།

Then the king said, ‘We ought to pay homage to the tutelary deity Thugs rje chen po’. After they paid homage in the presence of Thugs rje chen po in the temple hall, [the king] spoke face to face with the minister sNa chen po: ‘Great Zhang minister, in this snowy kingdom royal law should be transformed into religious law. May my descendants act according to the royal and religious laws. Five generations after me, an emanation of ʼJam dpal, named Khri srong sde btsan, will arise as a dharma protector king. He will spread the true doctrine and will, himself, finally become truly and completely enlightened.’

Volume 2

Part A contains 80 chapters, consisting of the personal instructions (zhal gdams) on the stages of the Buddhist path (lam rim) by the dharma-protector King Songtsen Gampo, ranging from the faults of samsara to the pith instructions on self-liberation.

Chapter 1 The eight instructions concerning request and receiving [Buddhist dharma].

Chapter 2 The eight instructions concerning recognition instruction.

Chapter 3 Concerning the twelve command instructions.

[1975, p. 34, l.5]

ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོའི་སྤྲུལ་པ་ཆོས་སྐྱོང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོས་སྲས་པོ་ལ་གདམས་པ། །རྒྱལ་བུ་ལྷ་སྲས་ཉོན་ཅིག །རྒྱལ་སྲིད་ཆོས་ཀྱིས་མ་བཟུང་ན། །འཇིག་རྟེན་རྒྱལ་སྲིད་ངན་སོང་འཁོར་བའི་རྒྱུ། །ཚེ་དིའི་རྒྱལ་སྲིད་ཆོས་དང་ཅི་མཐུན་གྱིས། །སློབ་དཔོན་ཞབས་འདེགས་བཀའ་ལ་འདྲི་འདོན་གྱིས།

The manifestation of Mahākarunika, the religious protector, King Songtsen Gampo, taught his son as follows: ‘Listen to me, divine prince. If you do not rule according to the dharma, your worldly kingship will become the cause of a hellish cycle of existence. In this life, you should rule in accordance with the dharma. Serve your religious masters and promulgate their teachings.

Then follow instructions to care for both outer and inner retinue with peace and provisions, to care for wives and respect ancestors, to engage in religious practice, and to act with compassion.

[1975, p.35, l.2]

།མཐོ་རིས་སྐས་ལ་འཛེག་པའི་དགེ་བཅུ་དང་དུ་ལོང། །ངན་སོང་གཡང་སར་འཁོར་བའི་མི་དགེ་བཅུ་པོ་སྤོངས།

Practise the ten virtues, which form a ladder to the higher realms. Reject the ten non-virtues, which lead to the precipice of a cycle of inferior existence.

There is then an admonishment to act with the next life in mind and to practise generosity.

[1975, p.35, l.3]

རྒྱལ་སྲིད་མཐའ་རུ་རྒྱས་ཀྱང་ཤི་བའི་ནང་པར་གཅིག་པུར་འགྲོ་བས་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོ་བསྒྲུབས། །ཕོ་བྲང་གནས་ཁང་བཟང་ཡང་གཏན་དུ་བསྡད་དབང་མེད་པས་ཞིང་ཁམས་དག་པར་སྦྱོངས། །རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དམ་པར་བསྡམས་ཀྱང་སྡིག་དང་ངན་སོང་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་བདེ་ལ་ཁོད།

Even though your dominions have extended their borders, you will go alone at the time of death, so you should practise the veneration of Mahākarunika. You cannot stay in the fine palace forever, so you must meditate on the pure Buddha-realms.

Even though the royal law has been strictly imposed (bsdams), it is the cause of sin and bad rebirth, so you must establish the religious law (chos khrims) well.

Then follows advice on how to rule, including training in meditation, treating subjects as one would one’s children, keeping the tantric vows, and acting in accordance with the dharma. The section concludes with:

[1975, p.36, l.3]

།ལྷ་སྲས་རྒྱལ་བུ་ལ་གདམས་པ། རྒྱལ་སྲིད་ཆོས་དང་བསྟུན་ཅིག་པའི་ཞལ་གདམས་སོ།

This is the instruction to a divine prince for bringing together kingship and the dharma.

Part B of volume 2 has six sections, four of them royal advice on the more esoteric aspects of Buddhist praxis, culminating with two sections of general advice to his subjects in the snowy land.

Footnotes:

- Kongjo is also known as Wencheng. ↩