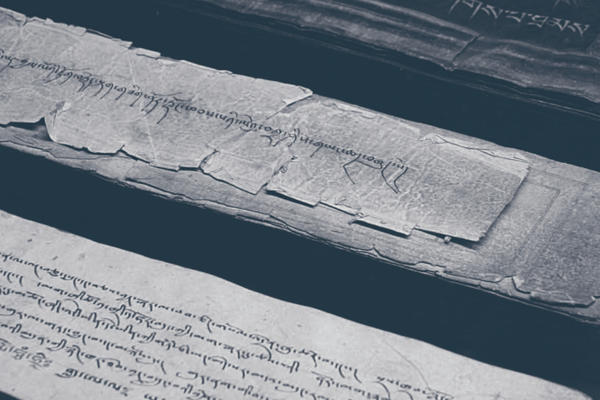

The Lde'u Chronicles

Chos ‘byung chen mo bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan & rGya bod kyi chos ’byung rgyas pa

Introduction

Two related texts, written in the thirteenth century, contain substantial sections describing the legislative and administrative activities of Songtsen Gampo. They are generally referred to as the Lde'u of Jo sras (Chos ’byung chen po bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan) of lDe’u Jo sras (Jo sras) and Mkhas pa lde'u (Rgya Bod kyi chos ’byung rgyas pa). Jo sras is the briefer text and is quite possibly earlier, while lDe’u is more detailed. van der Kuijp (1992) and Dotson (2006) suggest that both date from the mid to late thirteenth century. Cabezón (2013: 267–69) suggests that Jo sras may have been written slightly earlier, by someone who was part of a lineage of Padampa Sangyé’s Pacification teachings. There are references to Nyingma texts, but the authors do not mention either the Sakyapa or the Kagyupa schools of Buddhism (van der Kuijp 1992: 473).

Download this resource as a PDF:

The texts, their sources, and later use

Both texts are in two parts. The first is a long exposition of Indian Buddhism, presented as a commentary on a (non-extant) verse text. The second part is a history of Buddhism in Tibet, presented as a genealogy of the Tibetan royal families. It continues into the period of the phyi dar (the second diffusion of Buddhism) and, in the case of lDe’u, into the thirteenth century.

Within the second part is a long section, which is sometimes known as The Section on Law and the State (SLS). It describes the legislative and administrative activities of Songtsen Gampo. It outlines different aspects of his government in considerable detail, including the division of Tibet into thousand-districts (stong sde). It includes lists of different types of ministers, their duties and ranks, and different types of law.

In a detailed analysis and translation of the SLS, Dotson (2006) traces correspondences between parts of this section and what is known of law and administration in the Tibetan empire, including from Old Tibetan sources. He suggests that imperial catalogues—records of administrative measures—must have formed the basis for much of the detail and structure of the SLS.

Both texts list different types of law—five and six, respectively. Jo sras claims that the Thang yig chen mo—a non-extant, probably early ninth-century, chronicle—is a source for one of these types of law.

This section seems to be a source for a short section in the fourteenth-century rGyal po bka’ thang yig and for a very similar, although considerably longer and more detailed, section in the fifteenth-century mKhas pa’i dga ston. Neither the lDe’u nor Jo sras is referred to by other Tibetan authors, however, which suggests that they were, in general, little known in Tibet (van der Kuijp 1996: 469).

Primary sources

Chos ‘byung chen mo bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan. 1987. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang. [Jo sras] BDRC: W20831

mKhas pa lDe’us mdzad pa’i rGya Bod kyi chos ‘byung rgyas pa. 1987. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang. [lDe’u] BDRC: W21784

mKhas pa lDe’us mdzad pa’i Rgya Bod kyi chos ’byung rgyas pa. 2013. Delhi: Bod kyi gtsug lag zhib dpyod khang. [lDe’u]

References

Cabezón, José. 2013. The Buddha's Doctrine and the Nine Vehicles: Rog Bande Sherab's Lamp of the Teachings. Oxford: University Press.

Dotson, Brandon. 2006. Administration and Law in the Tibetan Empire: The Section on Law and State and its Old Tibetan Antecedents. DPhil thesis, University of Oxford. [available at https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/3358/1/DotsonDPhil.pdf]

Hill, Nathan. 2015. The sku bla rite in Imperial Tibetan Religion, Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 24: 49–58

van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1992. Tibetan Historiography. In J.I. Cabezón and R. Jackson (eds), Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre. Ithaca: Snow Lion.

Uebach, Helga. 1989. Notes on the Section of Law and State in the Chos-ʼbyung of Lde’u. In S. Ihara and Z. Yamaguchi (eds), Tibetan Studies. Narita: Naritasan Shinshoji.

A recent translation of this text corpus by Dan Martin has been published in the Library of Tibetan Classics, Martin, Dan. 2022. A history of Buddhism in India and Tibet : an expanded version of the Dharma’s origins made by the learned scholar Deyu. Wisdom Publications in association with the Institute of Tibetan Classics.

Extracts

Outline

1 On the teachers of the doctrine and their commentaries (pp. 5–90)

2 The emergence of the doctrine in Tibet (pp. 90–99)

3 The royal genealogies (pp. 99–108)

4 The activities of Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po) (pp. 108–18)

5 The descendants of Songtsen Gampo (pp. 118–22)

6 How Tri Song Detsen (Khri srong lde btsan) built the Samye Tsuglakhang (bSam yas gtsug lag khang) (pp. 122–33)

7 The succeeding kings (pp. 133–54)

8 The spread of the doctrine in the post-imperial period (pp. 154–63)

Extracts

The royal genealogies

In the account of the historic kings is a description of the activities of Nyatri Tsenpo (gNya’ khri btsan po).

[p. 102]

དེ་ནས་ཕྱིང་བ་སྟག་རྩེར་བྱོན་ཏེ་དར་དཀར་གྱི་ཡོལ་བ་དགུ་རིམ་བགྱིས་ནས། བླའི་སྐུ་ཡ་རབས་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་བསྐོར་ནས། གཙུག་ལག་གི་ཐང་ཁྲིམས་ནི་ལྷའི་ལུགས་སྒྲུང་དང་ལྡེའུ་ཙམ་ནི་བྱུང་། དགོངས་པ་འཕྲུལ་གྱི་རས་ཆགས་པས། གསང་གྲོས་རྣམ་གསུམ་གྱིས་ཕྱི་ནང་གི་དམིགས་ཕྱེ། མི་ལ་ཆད་རྣམ་གཉིས་དང་བཞེད་རྣམ་ལྔས་བོད་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་བཙས་ཡིག་ཚང་སྡེ་དགུ་དང་དཔའ་མཚན་རྣམ་བརྒྱད་བཀའ་རིམ་པར་གནང་ཏེ། ཛམ་བུ་གླིང་ན་མཐའ་བཞིའ་རྒྱལ་པོ་བཞི་ཡང་དཔྱ་འབུལ་ལོ།

Then he (Nyatri Tsenpo) went to Tiger Peak in Phying ba and acquired nine layers of white silk drapes. The nobility wrapped them around the noble (king’s) body (bla’i sku).1 In the law (thang khrims) of ancient tradition (gtsug lag) the deity legends (lha’i lugs sgrung) and riddles (lde’u) were manifest. When [his] thoughts turned towards the magical cloth (ʼphrul gyi ras chags), three secret pieces of advice opened [his] eyes to inner and outer [affairs]. Through two decisions and five proclamations, given in a series of oral edicts, he gave to the people the nine insignia of rank (yig tshang)2 of the newly-established laws of Tibet and the eight characteristics of heroes (dpa’ mtshan).3 In the wider world, he offered taxation [powers] to the four kings of the four borders.

The activities of Songtsen Gampo

After describing his birth and ascent to the throne, the Khotanese monks are briefly mentioned: they received a prophecy from Songtsen Gampo, as the emanation of Avalokiteśvara (sPyan ras gzigs) (p. 108).

The king’s ministers are listed, along with the fact that he took queens from China, Nepal, and Zhang Zhung (pp. 108–09).

There is then an outline of the administrative measures introduced by Songtsen Gampo. These include:

[p. 109]

ཁྲིམས་རྣམ་པ་ལྔས་བོད་སྤྱིར་བཅིངས།

The five types of law that bound Tibet.

And:

[p. 110]

མི་ཆོས་བཅུ་དྲུག་གིས་སྤྱོད་ལམ་གྱི་གཞི་བཟུང་། ལྷ་ཆོས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལ་དོན་གྱི་དཔེ་བླངས། ལུས་ཀྱི་དགེ་བ་སྤྱད་པར་བསྐུལ་བས་མཐོ་རིས་དང་ཐར་པའི་ལམ་བསྟན་ནོ།

Ways of behaving according to the sixteen human customs (mi chos bcu drug) were established. The ten virtues of the divine customs (lha chos dge ba bcu) were used as a model. Through encouragement of the practice of the bodily virtues, a path to the higher realms and to liberation was demonstrated.

The text continues with further detail on the four horns, the watch posts, the subjects and ministers, the che (ministers), the heroes, the clans and territories, workers, rulers, herdsmen, and traders (pp. 110–13).

It describes five kinds of laws:

[p. 113]

ཁྲིམས་རྣམ་པ་ལྔ་ནི། རྗེའི་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་ཇི་ལྟར་རྩལ་པ་དབང་གཅད་སྤྱི་ཁྲིམས། བསྐོས་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་བཞིའི་སྤྱོད་ལམ་ལ་ལྟོས་བཅས་པ་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་དཔེ་བླངས་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས། བོད་ཀྱི་ཐང་ཡིག་ཆེན་པོ་བཀོད་པ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་འབུམ་གསེར་ཐང་ཤ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་ཁྲིམས། དབུལ་པོ་ཐུབ་དཀའ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་མི་རྒོད་བཙན་ཐབས་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས། འཛངས་པ་འཕྲུལ་ལྕགས་ལ་བྱས་པའི་མདོ་བློན་ཞུས་བཅད་དང་ལྔའོ།

Concerning the five kinds of laws: on the orders of the lord, there was a general law to create divisions of power; by attending to the conduct of the four appointed kings, a law was modelled on the kingdom; on the basis of the Bod kyi thang yig chen po, the legal code of ʼBum gser thang sha ba can was created; on the basis of the poverty that is hard to overcome the law for controlling wild people was created; on the basis of the ʼDzangs pa ʼphrul lcags, a decision was made at the request of the mDo blon,4 making five.

The text then describes five kinds of statutes (zhal mchu) (concerning strongholds, livelihoods, wealth, men, and ritual specialists and monks). It lists five kinds of soldiers and six types of armour.

Then:

[p. 113–14]

ཁྲིམས་ཚིག་སུམ་བཅུ་རྩ་དྲུག་ལ་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅུ་གཉིས་ལ་བསྟོད་པ་ལ་གསུམ། སྨད་པ་གསུམ། མཛད་པ་གསུམ། མི་མཛད་པ་གསུམ་ལ་སོགས་པའོ། བླའི་རྐྱེན་དྲུག་ནི། ཡ་རབས་དང་ཞང་བློན་གྱི་རྐྱེན་དུ་ཆོས་དང་ཡིག་ཚང་བསྐོས། མ་རབས་གཡུ་པོའི་རྐྱེན་དི་བྲོ་བོན་ཟེར་དང་ཐགས་བསྐོས། འཛངས་པའི་རྐྱེན་ཏུ་ཡིག་ཚང་དན་པའི་རྐྱེན་དུ་སྟག་རྒྱ། དཔའ་བོའི་རྐྱེན་དུ་གུང་སྟག སྡར་མའི་རྐྱེན་དུ་ལྦ་དོམ་བསྐོས་སོ།

Within the thirty-six legal codes there were twelve royal laws, consisting of three praises, three shames, three deeds, three non-deeds, and so on. As regards the six superior rkyen (qualities): religion (chos) and insignia were established as the indications (rkyen)5 of nobility and the ministerial aristocracy; the saying of oaths6 and thags were established as the indications of the lower classes; texts were established as the indications of the wise; the tiger seal was established as the indication of the dan pa; the leopard [and] tiger were established as the indications of the brave; the fox and the bear7 were established as the indications of the cowardly.

The text continues with the four kinds of pleasure and the seven and a half wise men (pp. 114–15). It concludes:

[p. 115]

དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཚེ་སྨད་ལ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ས་བཟུང་ནས་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་སྲོལ་བསྟོད་དེ།

Then, in the latter part of his life, the king achieved the status of dharmarāja and promoted the traditions of the religious law.

Footnotes:

- This phrase is very obscure. It is possible that bla refers to officials (cf. Dotson), in which case the officials would be wrapping the drapes around their excellent bodies. The sku bla is also a deity associated with the emperor in Old Tibetan sources (Hill 2015). ↩

- This phrase appears in lDe’u (p. 263/ p. 166). ↩

- This phrase appears in KhG (p. 191), where there are six, while in lDe’u (1987, p. 271) there are six dpa’ rtags. ↩

- The equivalent passage in lDe’u is mdo lon zhu gcod kyi zhal lce, suggesting a summary of what is offered and received, that is, the evidence (see the lDe’u extracts, at p. 8). ↩

- This is to read ryen as a metonymy, referring both to the quality, itself, and to the markers of those who possess that quality. ↩

- bro bor for bro bon. ↩

- wa dom for lba dom. ↩

Outline

The outline and extracts below are based on the 2013 edition.

Discourse on Buddhist doctrine [1987: pp. 1–181] (2013: pp. 3–115)

History of Buddhist doctrine coming to Tibet [1987: p. 181–411] (2013: pp. 116–256)

The royal genealogies [1987: p. 191–] (2013: p. 121)

Songtsen Gampo [1987: p. 252–] (2013: p. 159)

Administrative and legal measures [1987: pp. 253–77] (2013: p. 159–73)

The founding of the Lhasa temples and other activities [1987: pp. 277–99] (2013: pp. 174–87)

Subsequent kings and their activities [1987: p. 299–] (2013: p. 187)

Extracts

Songtsen Gampo’s administrative and legal measures:

[1987: pp. 252–53] (2013: pp. 159–160)

དེ་ཡང་མེས་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ་འདི་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ་ཡིན་ཏེ། ལི་ཡུལ་གྱི་བན་དྷེ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་སྒྲུབ་པས། ལུང་བསྟན་བྱུང་སྟེ། ད་ལྟ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་གཅིག་ཏུ་སྤྲུལ་ནས་བོད་རྣམས་འདུལ་གྱི་ཡོད་ཅེས་པ་བྱུང་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་ཁྲ་འབྲུག་ཏུ་བྱོན་པ་དང་། དབུ་རིའི་ང་ནས་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོས་ཆད་པ་བཅད་པའི་མིག་གི་ཕུང་པོ་དང་། སྒྱིད་པ་བྲེགས་པ་ལ་སོགས་པའི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་ཐོས་པས་མ་མོས་ནས། ལྷ་ས་རུ་བྱོན་པ་དང་། ལྷ་ས་དན་འབག་གི་ནང་ན་ཡང་དེ་ལྟར་འདུག་པ་ལ་མ་མོས་ཏེ། སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ་ཡོད་ཟེར་ཙ་ན་བདུད་ཀྱི་སྤྲུལ་པར་འདུག་པ་སྙམ་ནས་བྲོས་པ་དང་། སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོས་གཡོག་པོ་ལ་རྟ་བསྐྱོན་ནས་ཟློག་པ་ལ་བཏང་སྟེ་དབུ་གཞུ་༼ཞྭ་༽ ཕུད་པས་ཞལ་བཅུ་གཅིག་པར་མཐོང་ནས། ཁྱོད་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོའི་སྤྲུལ་པར་འདུག་པ་ལ། མིག་འབྱིན་པ་དང་སྒྱིད་པ་འབྲེག་པ་ཙུག་ལགས་ཞེས་ཞུས་པས། སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོའི་ཞལ་ནས་ངས་བོད་འདུལ་བའི་ཆེད་དུ་སྤྲུལ་པ་བྱས་པ་ཡིན། ངས་དང་པོ་སེམས་བསྐྱེད་ནས་ད་ལྟ་ཡན་ཆོད་དུ་སེམས་ཅན་གྱི་བ་སྤུའི་བུ་ག་གཅིག་ལ་ཡང་གནོད་པ་སྐྱེལ་མ་མྱོང་། ཁྱོད་གཉིས་དངོས་གྲུབ་ཅི་འདོད་གསུངས་པས། ངེད་རང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ཡུལ་དུ་རྟོལ་བ་གཅིག་འདོད་ཟེར་ནས། འོ་ན་མིག་བཙུམ་གྱིས་ཤིག་གསུངས་ནས་ལག་ཏུ་བྱེ་མ་སྤར་བ་རེ་གཏད་བཞག་པས་ཁོ་རང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ཡུལ་དུ་སླེབས་ནས་བྱེ་མ་གསེར་དུ་སོང་འདུག་སྐད།

Moreover, this ancestor, Srong btsan sGam po, was the incarnation of sPyan ras gzigs. Two Khotanese monks received a revelation through meditating on sPyan ras gzigs [in which he said]: ‘Now that I have manifested as the king of Tibet, I am converting the Tibetans’. They arrived at Khra ’brug in Tibet, and in the central district they heard stories about Srong btsan sGam po inflicting punishments, including having eyes pulled out and knees cut off, which they could not believe. They went to Lhasa, but they could not believe that it was him (sPyan ras gzigs) at Dan ’bag. They said to themselves: ‘It is said that he is the emanation of sPyan ras gzigs, but he is a demonic emanation’, and they departed.

Srong btsan sGam po ordered a servant to go by horse to turn them back. He took off his headgear so that they could see the eleven faces. ‘Since you are an emanation of Thugs rje Chen po (Mahākārunikā), how is it that you remove people’s eyes and cut off their knees?’ they asked. Srong btsan sGam po replied: ‘I have manifested in order to convert Tibet. I first generated the mind of enlightenment. Up to the present day, I have not harmed a single hair of a sentient being. What spiritual accomplishments do you two seek?’ ‘We just wish to go back to our own country’, they replied. ‘Well then, close your eyes’, he said, and tossed a handful of sand and fulfilled their hopes and wishes. They arrived in their country and found that the sand had turned to gold. So it is said.

The text continues by describing the activities of Songtsen Gampo as a young man, when he divided Tibet into the four horns and brought the twelve minor kingdoms under his dominion. He appointed ministers, soldiers and border guards, herdsmen, merchants, and so on. [1987: p. 254] (2013: p. 160)

དུས་དེ་ཙ་ན་ཚན་བཅུ་སྡེ་བཅུ་ལགས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ཆོས་ནི་བོད་ཀྱི་སྤྱི་ཆིངས་བྱས། ཞལ་མཆུ་རྣམ་པ་ལྔས་ནང་གི་འཁོན་སྦྱངས། དམག་རྣམ་པ་ལྔས་ཕྱིའི་དགྲ་འདུལ། གོ་རྣམ་པ་དྲུག་གིས་ནང་གི་སྲོག་སྐྱབས། ཚིག་དྲུག་དྲུག་སུམ་ཅུ་རྩ་དྲུག་གིས་བོད་བདེ་ལ་བཀོད། བླའི་རྐྱེན་དྲུག་གིས་འགྲོ་བའི་དོན་བྱེད། འབྲོག་ཐུལ་གྱིས་བགོས། ཞིང་ཐེ་གུས་བཅལ། དགུང་བློན་ཆེན་པོ་བ་བདུན་གྱིས་རིང་ལ། ཆུ་ལ་གྲུ་བཙུགས། ལ་ལ་ལབ་རྩས་བརྩིགས། དམག་མིའི་དཔོན་བསྡུས། མཐའི་རྒྱ་དྲུག་ བཏུལ་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་སྟོང་སྐྱེད། བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་ནན་བསྡམས། རྗེའི་བཀའ་བསྩལ་ལ་གྲོས་ཀྱི་རྒྱུ་བྱས། འབངས་ཀྱི་མཆིད་ཚིག་ལ་གྲོས་ཀྱི་སྤུན་བྱ་བགྱིས། དུས་དེ་ཙ་ན་མི་ཆོས་བཅུ་དྲུག་གིས་སྤྱོད་ལམ་གྱི་ཁ་བཟུང། ལྷ་ཆོས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལ་དོན་གྱི་དཔེ་བླངས་ནས་ལུས་ངག་གིས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་སྤྱད་པས་མཐོ་རིས་དང་ཐར་པའི་ལམ་སྟོན།

At that time, there were laws and customs (khrims chos) concerning the ten tshan (larger administrative districts) and the ten sde (smaller sub-districts), which bound Tibet, in general. The five kinds of edict (zhal mchu) cleared up internal hostility. The five types of soldiers subdued external enemies. The six kinds of armour protected inner life forces. The thirty-six (six by six) codes (tshig) created well-being in Tibet. The six qualities (rkyen) of the superior were for the benefit of living beings. The pastures were apportioned according to the herds of livestock (thul).1 The fields were measured out into the gu. During the time of the seven great ministers (dgung blon chen po), boats were established for rivers, shrines (lab rtse) were built on mountain passes, and the army leaders were gathered together. The Chinese and Turks on the borders having been conquered, the Tibetan thousand-districts (stong) were established. [The people] were bound with unshakeable edicts (bka’ khrims). The orders of the lords were based on consultations. [They] gave brotherly advice on the petitions of the subjects.

At that time, the sixteen rules of human conduct (mi chos) governed behaviour. When rules for religious conduct (lha chos) had been established on the basis of the ten virtues, the bodily and verbal practice of the ten virtues showed the way to the higher realms and liberation.

The text continues by specifying the circumstances in which the laws were made by Songtsen Gampo. It then gives an outline of the following provisions, concerning the different administrative measures introduced by the emperor. It then moves into the specifics, starting with the ten tshan (the sixteen administrative districts in each of the four ‘horns’ of Tibet), and the ten sde (the eight thousand-districts, the minor thousand-districts, and the royal guard regiment, in each horn). Then it describes the nine bkra (inscribed wooden slips) and the nine che (ministers):

[1987: pp. 261–63] (2013: p. 165)

བཀྲ་དགུ་ནི་བྱང་བུ་དགུ་བཀྲ་ལ་བྱ་སྟེ། བྱང་གཟས། ཟང་ཡག སྐེད་ཁྲ། སྦྲུལ་མགོ དམིག་ནག མཆུ་སྙུང་། ཐེན་བྱང་། ཁ་དམར། རྒྱ་བྱང་ངོ་།།

བྱང་བུ་གསུམ་ནི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་སྤྱིའི་བྱང་བུ། ལྔ་ནི་བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་བྱང་བུ། གཅིག་ནི་ཀུན་ལ་རྒྱུག་པའོ། ཞལ་ལྕེའི་བྱང་བུ་གསུམ་ནི། ཟང་ཡག སྐེད་ཁྲ། ཁ་དམར་རོ། རྒྱ་བྱང་ནི་སྤྱིར་རྒྱུག་པའོ། བྱང་བུ་ལྔ་ནི་བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་བྱང་བུ་སྟེ། ཞལ་ལྕེ་ན་ལྔ་དང་སྦྱར།

མི་སྟོང་དགེའི་ཞལ་ལྕེའི་དུས་སུ། ཤགས་ཀྱི་མགོ་རྒྱངས་སུ་ཡང་། ཡིག་ཚང་དང་། སྟོང་ཐང་དང་། ཆད་པ་བཀའ་བཀྱོན་ལ་སོགས་པ་བྲིས་ནས། ཞལ་ལྕེའི་གྲ་རུ་སྲིང་བ་དེ་ནི། བྱང་གཟས་ཞེས་བྱའོ། དེའི་ལན་ཤགས་ཀྱི་བྱང་བུ་སྐུར་བ་ལ་སྦྲུལ་མགོ་ཞེས་བྱ། ཡང་ལན་ལ་ཤགས་འདེབས་པའི་བྱང་བུའི་མིང་ནི་དམིག་ནག་ཞེས་བྱ། དུས་དེ་ཙ་ན་བླ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་མཆིད་ཤགས་ལ་གསུམ་ལས་མེད་པའི་གཏན་ཚིགས་དེ་ཡི་། : the ten ན གཉེན་བྱེ་བྲལ་གྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་བྱས་པའི་དུས་སུ། ཞལ་ལྕེའི་གྲ་རུ་སྲོང་བའི་མིང་ནི་ཐེན་བྱང་ཞེས་བྱ། ཤགས་ཀྱི་མགོ་རྒྱངས་སུའང་། སྙོན་སྟོབས་དང་དགྲ་ཐབས་ཇི་ལྟར་བྱུང་བ་འབྲི་བ་ལགས། སྙོན་རྟོལ་དཀར་མའི་ཞལ་ལྕེའི་དུས་སུ། ཞལ་ལྕེའི་གྲ་རུ་སྲིང་བའི་བྱང་བུའི་མིང་ནི་མཆུ་སྙུང་ཞེས་བྱ་སྟེ། བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་བྱང་བུ་ལྔའོ།།

ཞལ་ལྕེའི་བྱང་བུ་གསུམ་ནི། ཟང་ཡག་བྱ་བ་བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་ཤགས་དང་སྦྱར་ནས་དྲང་པོར་གཅོད་པ་ལ་ཟེར་རོ། །སྐེད་ཁྲ་ནི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་ཡོན་པོར་གཅོད་པ་ལ་ཟེར་ཏེ། བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་ནོར་ཟ་བ་ལ་ཟེར་རོ། །བྱང་བུ་ཁ་དམར་ནི་ཁ་དམར་འདོགས་པ་ལ་ཟེར་ཏེ། བྱང་བུ་གསུམ་མོ། །རྒྱ་བྱང་ནི་ཉེས་པའི་སྐྱོན་ཐམས་ཅད་བཟང་པོའི་རྒྱས་བཏབ་ནས་བྱང་དུ་འཇུག་པ་ལ་རྒྱ་བྱང་ཟེར་རོ། །དེ་ནི་བཀྲ་དགུ་ཞེས་བྱའོ།།

As regards the nine bkra, these were the nine clear (inscribed) wooden slips (byang bu dgu bkra): the accusation slip (byang gzas);2 the good undefiled (zang yag); the striped middle; the snake’s head; the black hole; the swallow; the drawing-out slip; the red-notched slip; and the seal slip.

Three of the slips are general slips for court orders (zhal lce); five are the parties’ (blo yus)3 slips; and one is used for everything.

As regards the three order slips: these are the good undefiled, the striped middle, and the red-notched. The seal slip is used for everything.

As regards the five parties’ slips: they correspond to the five na orders.4 When an order [is sought] for suitable blood money, to initiate the law-suit5 the insignia of rank, the blood price, the punishment contended for, are written down. The means by which this is sent to the court (zhal lce’i gra) is called the accusation slip (byang gzas). The slip with the argument in response rejecting [the accusation] is called the snake’s head. Further arguments in response are given by what are called the black hole slips. At this stage, [each] party may only put forward three arguments (mchid shags). The means by which notice of the separation of the compatriots is sent to the court is called the drawing-out slip. The initiation of the law suit is like this. Strong denials and means of refutation are written down on a slip. When there is an order for oath-helpers to expose falsehoods, the means by which notice of this is sent to the court is called the swallow slip. These are the five parties’ slips.

As regards the three general slips for court orders: the good undefiled slip affirms the claims of [one of the] parties and determines that they are truthful; the striped-middle slip indicates that it is false and states that that party’s wealth is to be confiscated; the red-notched slip indicates that instructions are attached. These are the three slips.

As regards the seal slip: [in connection with] faults and defects, if a good seal is attached at the beginning of the slip, this is called the seal slip.

These are known as the nine bkra.

[1987: p. 263] (2013: p. 166)

ཆེ་དགུ་ནི། ལས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱི་བློན་པོ་དགུ་ལ་བྱའོ། །དགུང་བློན་ཆེ་འབྲིང་ཆུང་གསུམ། ནང་བློན་ཆེ་འབྲིང་ཆུང་གསུམ། བཀའ་ཡོ་འགལ་འཆོས་པ་ཆེན་པོ། འབྲིང་པོ་། ཆུང་བ་གཉིས་༼གསུམ་༽ པོ་དེ་འབངས་གཞན་པས་ཆེ་བས་ན། ཆེ་དགུའོ།།

དེ་ལ་དགུང་བློན་ཆེན་པོའི་ལས་ཐབས་ནི། ཁྱོ་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ་ཕྱིའི་ཚིས་བྱས་ནས་ཕྱི་རྒྱ་རླབས་ཀྱིས་གཅོད་པའོ།། ནང་བློན་གྱི་ལས་ཐབས་ནི། མོ་བཙུན་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ། ནང་གི་ཚིས་བྱེད་པའོ། །བཀའ་ཡོ་འགལ་འཆོས་པ་ནི་བདམས་ཀྱི་ཕུར་པ་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ། ལེགས་ན་དགྲའི་བུ་ལེགས་ཀྱང་བྱ་དགའ་གསོལ། ཉེས་ན་རང་གི་བུ་ཉེས་ཀྱང་ཆད་པ་གཅོད་པའོ། །དགུང་བློན་ཆེན་པོ་ནི་འགྲན་གྱི་ཟླ་མེད་པ་སྟེ། བསད་ན་སྟོང་ཐང་༼ཁྲི་༽ཆིག་སྟོང་ཡོད་དེ་ཆེའོ། །ཡིག་ཚང་གཡུའི་ཡི་གེ་ཆེའོ། །དགུང་བློན་འབྲིང་པོ། ནང་བློན་ཆེན་པོ་གཉིས་ནི། སྟོང་ཐང་མཉམ་སྟེ་ཁྲི་ཡོད། ཡིག་ཚང་གཡུའི་ཡི་གེ་ཆུང་བའོ། །དགུང་བློན་ཆུང་བ། ནང་བློན་འབྲིང་པོ་བཀའ་ཡོ་འགལ་འཆོས་པ་གསུམ་ནི་སྟོང་ཐང་དགུ་སྟོང་ཡོད་པའོ། །ཡིག་ཚང་གསེར་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་ཆེན་པོའོ། །ནང་བློན་ཐ་ཆུང་དང་ཡོ་འགལ་འཆོས་པ་འབྲིང་པོ་གཉིས་སྟོང་ཐང་བརྒྱད་སྟོང་། ཡིག་ཚང་གསེར་ཡིག་ཆུང་བའོ། །ཡོ་འགལ་འཆོས་པ་༼ཆུང་བ་༽ལ་སྟོང་ཐང་བདུན་སྟོང་ངོ་། །ཡིག་ཚང་འཕྲ་མེན་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་མཐོའོ། དེ་ཚོ་བཀྲ་དགུ་ཆེ་དགུའོ།།

As regards the nine che, they are the ministers who carry out all the [official] work. There are three ranks of great ministers, high, middle, and low; there are three ranks of interior ministers, high, middle, and low; there are three ranks of justices (bka’ yo ’gal ’chos pa), high, middle and low. Being greater than other subjects, they are called the nine che (great ones).

The duty of the high-ranking great ministers is to act like a husband, to deal with external affairs and to resolve them completely. The interior ministers are to act like a wife, and to deal with internal affairs.

The justice is to act like a chosen ritual dagger: to the good, even if it is the son of an enemy, he gives rewards; to the bad, even if it is his own son, he metes out punishment.

As for the highest ranking of the great ministers, he is unrivalled. If he is killed, his compensation price is [as high as] eleven thousand. His insignia of rank is the large turquoise.

As for the middle ranking of the great ministers and the highest ranking of the interior ministers, the compensation price of both of them is ten thousand and their insignia of rank is the small turquoise.

As for the lower ranking great ministers, the middle ranking interior ministers and the justices, the compensation price of all these three is nine thousand, and their insignia of rank is the large golden insignia.

As for the lower-ranking interior ministers and the middle-ranking justices, the compensation price for these two is eight thousand, and their insignia of rank is the small golden insignia.

For the lower-ranking justices, the compensation price is seven thousand and their insignia of rank is the highest gilt insignia (ʼphra men).

These are the nine bkra and the nine che.

The text continues with the eight kha (trading centres) the eight khe (merchants), the eight kher (profits), the seven che (particular leaders), and the seven dpon (officials):

[1987: p. 266] (2013: p. 167)

དཔོན་བདུན་ནི་ཡུལ་དཔོན་གྱི་ལས་ཐབས། ཡུལ་ཆུང་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་རྩ་བ་དང་། མཐོ་མཐོ་རྫི། སྨ་སྨ་༼དམའ་༽ སྐྱོང་བ་ལགས།

As regards the seven officials, the duty of the regional officials (yul dpon) is to be the root of the law (khrims kyi rtsa) in the villages, to keep in line (lit. herd) the high, and to protect the low.

Then come the six great insignia, the twenty-one other insignia, the six qualities (rkyen), and the five bla (officials). Next are the five na:

[1987: pp. 267–69] (2013: p. 168–69)

ན་ལྔ་ནི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་སྣ་ལྔ་བྱ་སྟེ། མི་སྟོང་དགེའི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། གཉེན་བྱེད་ཚིས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། སྙོན་རྟོལ་དཀར་མིའི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། མདོ་ལོན་ཞུ་གཅོད་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། ཉེ་དུ་ལྷུམ་༼འདུམ་༽ ཆོས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེའོ།།

ཁྲིམས་སྣ་ལྔ་ནི། ཁྲི་རྩེ་འབུམ་བཞེར་གྱི་ཁྲིམས་དང་གཅིག སྟོང་འཇམས་ཆུན་ལག་གི་ཁྲིམས་དང་གཉིས། བཀའ་ལུང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དང་གསུམ། དབང་བཅད་སྤྱིའི་ཁྲིམས་དང་བཞི། འབྲོ་བཟའ་བྱང་ཆུབ་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་དང་ལྔའོ།།

དེ་ལ་ཁྲི་རྩེ་འབུམ་བཞེར་བྱ་བ་ནི། ས་བདག་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ནོར་སྟོར་ན་ཁྲིམས་༼ཁྲི་༽ ཆིག་སྟོང་། དགེ་འདུན་ལ་ཁྲིམས་ ༼ཁྲི་༽ སྨངས་༼དམངས་༽ ལ་སྟོང་། དེ་ཆེས་ནས་བཞག སྟོང་འཇམ་ཆུན་ལག་བྱ་བ་ནི། ཡུལ་གཞན་ནས་ནོར་སྟོར་ནས། ཡུལ་གཅིག་གི་ཕུ་རུ་བྱུང་ན། ཆད་པ་མདའ་ལ་བཅད་དེ། མ་འཐད་པར་བཞག དབང་བཅད་༼སྤྱི་༽ ཁྲིམས་བྱ་བ་ནི། རྗེའི་བང་སོ་རྩིག་པའི་དུས་སུ། ཉི་མ་རེ་ལ་ཕོ་མ་བྱུང་ན་ར་གཅིག མོ་མ་བྱུང་ན་བོང་བུ་གཅིག་གི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

།བཀའ་ལུང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ནི། ས་བདག་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ནོར་ སྟོར་༼བརྐུས༽ ན་བརྒྱ་འཇལ། དཀོན་ཅོག་ལ་བརྒྱད་ཅུ་འཇལ། འབངས་ལ་བརྒྱད་འཇལ་ལོ། །འབྲོ་བཟའི་ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་མ་ནི། སྐྱེས་པ་ལ་ཕོ་ཕྱག་སློབ། བཟའ་མ་ལ་མོ་ཕྱག་སློབ། ཕྱུག་པོ་ཡོང་གི་རྩ་བ་ཞིང་ལ་མུ་རྡོ་འཛུགས། སྟོན་དཔྱིད་ཀྱི་སྤར་ཁ་མཉམ་པའོ།།

As regards the five na, they are the five types of order that are to be made: an order concerning suitable blood money; the order that enumerates compatriots; the order for oath-helpers to expose falsehood; the order that determines the summary of what is offered and received;6 the practice of reconciliation [through/with] kinsmen.

As regards the five kinds of laws (khrims): the first is the law of Khri rtse ʼbum bzher; the second is the law of sTong ʼjams chun lag; the third is the proclaimed royal law; the fourth is the general law of the governors; and the fifth is the subordinate law of Lady ʼBro byang chub.

Regarding that of Khri rtse ʼbum bzher: if the wealth of a king and ruler is stolen, the compensation is ten thousand; for the sangha it is ten thousand and is set at a higher amount because the compensation for ordinary people is one thousand.

As regards the rule of sTong ʼjams chun lag: if property is stolen [by someone from] another area, and it appears in the upper part of that area, it is inappropriate to punish those from the lower part of that area.

As regards the laws of the governors: the rule is that when a lord’s tomb is being constructed, if a man does not appear for one day [there is a fine of] one goat; and if a woman does not appear, there is [a fine of] one donkey.

As regards the proclaimed royal law: if someone steals the property of a king, the compensation is one hundred-fold; the compensation for the sangha is eighty-fold; the compensation for ordinary people is eight-fold.

As regards the subordinate law of Lady ʼBro byang chub: husbands should be taught the duties of men, and wives should be taught the duties of women; the basis of wealth is to put boundary stones on one’s fields, and act in accordance with the astrological signs of autumn and spring.

The text continues with the five types of soldiers and provisions for their funerals. Then it specifies the five types of heroes:

[1987: p. 269] (2013: p. 169)

།དཔའ་ ༼དགེ་༽ སྣ་ལྔ་ནི། དཔའ་བོའི་དགེ་དགྲ་མགོ་ནོན་པའོ། མཛངས་པའི་དགེ་སྲིད་ཀྱི་མདུན་ས་ཟིན་པ། སྨྲས་པའི་དགེ་ཤགས་ཐེབས་པ། དྲག་པོའི་དགེ་ཕོ་ཁོག་ཆེ་བ། བསགས་པའི་དགེ་གཏོང་ཕོད་ནུས་པའོ།

As regards the five types of hero (dpa’): the quality (dge) of heroes is that they suppress enemies; the quality of the wise is that they rule the political council; the quality of advocates (smras pa) is that they make good arguments (shags); the quality of the powerful is that they are broad-chested men; the quality of accumulators [of wealth] is generosity.

The text continues with the four bka’ (orders), the four rtsis (accounts), the three khams, and the three customs (chos):

[1987: p. 269] (2013: p. 169)

ཆོས་གསུམ་ལ་བཀའ་ཆོས། དབྱང་ཆོས། རྩིས་ཆོས་སོ།

The three customs are: customs of speech (bka’ chos) (teachings), customs of music,7 and customs of astrology.

Then follows the pair and the ruler.

The text then announces the thirty-six laws and institutions. It continues with the six great principles (bka’ gros) and then the six laws (khrims):

[1987: p. 270] (2013: p. 170)

ཁྲིམས་དྲུག་ལ་ནི། གོང་གི་ཁྲི་རྩེ་འབུམ་བཞེར་གྱི་ཁྲིམས་དང་གཅིག་འབུམ་གསེར་ཐང་ཤ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་ཁྲིམས་དང་གཉིས། རྒྱལ་ཁམས་དཔེ་བླང་གི་ཁྲིམས་དང་གསུམ། མདོ་ལོན་ཞུ་བཅད་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་དང་བཞི། ཁབ་སོ་ནན་ཁྲིམས་དང་ལྔ། བཀའ་ལུང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དང་དྲུག་གོ

As regards the six laws: the first is the law of the great Khri rtse ’bum bzher; the second is the law of ‘Bum gser thang sha ba can; the third is the law that takes the kingdom as its model; the fourth is the law about deciding upon a summary of what is offered and received;8 the fifth is the law created at the insistence of the revenue collectors (khab so nan); and the sixth is the proclaimed royal law.

It continues with the six institutions, the six insignia of rank, the six seals, the six emblems of heroism, and then the six royal laws:

[1987: p. 270–71] (2013: p. 170)

དེ་ལ་བཀའ་ལུང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དྲུག་ལ། སྲོག་མི་གཅོད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་སྟོང་ཐང་གསོས་ཐང་བཅད་པ་དང་གཅིག མ་བྱིན་པར་ལེན་པ་ལ་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་བརྒྱ་འཇལ་དང་དཀོན་ཅོག་ལ་བརྒྱད་ཆུ་བ་འཇལ་དང་། སྐྱེ་བོ་ལ་བརྒྱད་འཇལ་དུ་བཅད་པ་དང་གཉིས། འདོད་པས་ལོག་པར་སྤྱད་འཇལ་པ་ལ། བྱི་འཇལ་སྣ་བཅད་པ་དང་མིག་དབྱུང་བར་བྱ་བ་དང་གསུམ། རྫུན་སྨྲས་ཀྱི་དྭགས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་དཀོན་ཅོག་དང་ལྷ་ཀླུ་གཉན་པོ་དཔང་དུ་བཙུགས་ནས་མནའ་བྱ་བ་དང་བཞི། ཁེངས་མི་ལྡོག་པ་དང་བང་སོ་མི་འདྲུ་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་དང་དྲུག་གོ །ཁྲི་རྩེ་འབུམ་བཞེར་ན་ཁྲིམས་བྱུང་ངོ་།།

As regards the six proclaimed royal laws: first is the law concerning the taking of life, which provides for blood money (stong thang) and wound price (gsos thang); the second concerns theft, and provides that for a king the compensation is one hundred-fold, for clerics it is eighty-fold, and for ordinary men it is eight-fold; the third concerns sexual misconduct and provides that the response to adultery is to cut off the nose and pull out the eyes; the fourth concerns doubts about lying and provides for the swearing of oaths taking the Jewels and the spirits—lha, klu, and gnyan—as witnesses; the laws concerning servants not revolting and not digging up tombs, makes six. These are the laws that appear in Khri rtse ’bum bzher.

The text continues with long sections concerning the six institutions, the four horns, civilian districts, workers, rulers, and herdsmen. Then there are shorter sections concerning the eighteen shares of power, and the upper, middle, and lower regiments. Then there is a section concerning the ministerial laws:

[1987: p. 275–76] (2013: p. 173)

བློན་ཁྲིམས་སྣོལ་མ་ནི། མཛད་པ་གསུམ། མི་མཛད་པ་གསུམ། བསྟོད་པ་གསུམ། སྨད་པ་གསུམ། མནར་དུ་མི་གཞུག་པ་གསུམ་ཏེ་བཅོ་ལྔའོ། །མཛད་པ་གསུམ་ནི། ཕྱིའི་དགྲ་བཏུལ་ནས་ནང་བདེ་བར་མཛད་པ་དང་། ནང་གི་ཚིས་བྱས་ནས་འཁོར་འདུ་བར་མཛད་པ་དང་། ལྷ་ཆོས་བྱས་ནས་སངས་རྒྱས་ཐོབ་པར་མཛད་པ་དང་གསུམ་མོ། །མི་མཛད་པ་གསུམ་ནི། ལྷ་ཆོས་ཡ་རབས་ཀྱི་རྐྱེན་ཁེང་པོ་ལ་མི་བསྟན། གསང་སྔགས་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་ནོར་དུ་མི་བཙོང་སྙིང་ལ་བཅངས། ཁེང་པོ་རྗེ་རུ་མི་དབྱུང་། མི་ཁྱད་མེད་པར་འགྲོ་བས་ཁེང་པོའི་བུས་བསྟོད་མི་ཐུབ་པས་སོ་ལ་བཞག་གོ །བསྟོད་པ་གསུམ་ནི། དཔའ་བོ་ལ་སྟག་གིས་མ་བསྟོད་ན། དཔའ་བོ་བྱས་པའི་དོན་མེད། མཛངས་པ་ལ་ཡིག་ཚང་གིས་མ་བསྟོད་ན། མཛངས་པ་ཡི་༼ཡིད་༽ ཞི་འགྲོ། ལེགས་པ་བྱ་དགས་མ་བསྟོད་ན། ལེགས་པ་བྱེད་པའི་རུ་མ་མེད། སྨད་པ་གསུམ་ལ། སྡར་མ་ལ་ཝ་ཞུས་མ་སྨད་ན། དཔའ་བོ་དང་སྡར་མའི་ཤན་མི་ཕྱེད། ངན་པ་ལ་ནན་ཐུར་མ་བྱས་ན་མཛངས་ངན་གྱི་ཤན་མི་ཕྱེད། ཉེས་པ་ལ་ཆད་པ་མ་བཅད་ན་ལང་༼ཤོར༽ རེངས་ལ་འགྲོ། མནར་དུ་མི་གཞུག་པ་གསུམ་ནི། ལུས་སྲོག་བསྐྱེད་པའི་ཕ་མ་མནར་ན་ལ་ཡོགས་འོང་ཞིང་མིས་འཕྱ་བས་མནར་དུ་མི་གཞུག མཆན་གྱི་བུ་ཚ་མནར་ན་དགྲ་ཡང་ཁྲེལ་ནས་འགྲོ་བས་མནར་དུ་མི་གཞུག ཟླ་རོགས་མནར་ན་སོ་ནམ་ཆག་ནས་མཐའ་མ་དབུལ་པོར་འགྲོ་བས་མནར་དུ་མི་གཞུག་གོ །དེ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་ལུགས་བསྟན་པའོ།།

As regards the combined ministerial laws: they were the three deeds, the three non-deeds, the three praises, the three shames, and the three non-harms, making fifteen.

As regards the deeds: by subduing external enemies, ensure interior peace; tend to internal affairs and gather your people around you; undertake religious practices (lha chos) to reach enlightenment; making three.

As regards the three non-deeds: since the divine religion is a quality of nobility, do not teach it to servants; since secret mantras (gsang sngags) are the cause of Buddahood, do not sell them for wealth but cherish them in your heart; do not set servants up as rulers—as there is no [visible] distinction between men, and since one cannot praise (elevate) the son of a servant, establish [visible] differences.

As regards the three praises: if heroes are not rewarded with [the insignia of] tigers, it will be meaningless to act like a hero; if the wise are not rewarded with literary insignia (yig tshang) they will have inactive minds; if those who do good deeds are not rewarded with things that please them, they will not inspire others to do good deeds.

As regards the three shames: if cowards are not shamed with [the insignia] of foxes, then it will not be possible to distinguish between heroes and cowards; if the wicked are not suppressed, it will not be possible to distinguish between the wise and the wicked; if criminals are not punished, then their bad habits (lang shor) will become engrained.

As regards the three non-harms: if you harm the parents who gave you life, then there will be retribution and people will scorn you, so do not allow this harm; if you harm your own child, then hostility and shame will result, so do not allow this harm; if you harm your wife, your merit will decrease and finally you will be impoverished, so do not allow this harm.

This is an account of the way in which the royal laws were created.

The text continues by describing the way in which the religious law (chos khrims) was created. It describes the development of good relations between China, Tibet, Nepal, and Zhang Zhung, the founding of one hundred and eight temples, and the invitations issued to princesses from China, Nepal, and Zhang Zhung. The author refers to the sBa’ bzhed as the source for this passage.

The text continues with further details about the temples that were built.

A later section describes subsequent kings and their activities. The passage on Ralpachan (Ral pa can) includes the following:

[pp.363–64] (2013: 224–27)

དེ་དུས་ཡན་ཆད་དུ་དགྲ་ཐབས་ཟབ་མོས་ཕྱིའི་དགྲ་ཐུལ། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་གསེར་གྱི་གཉའ་ཤིང་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ། སྦོམ་ལ་ལྕི་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དར་གྱི་མདུད་པ་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ་འཇམ་ལ་དམ། མི་ཆོས་སོག་མའི་ཕོན་ཐག་དང་འདྲ་སྟེ་མང་ལ་འདུས། རྗེ་བླ་ན་བཞུགས་པ་ནི་ཐུགས་སྒམ། འབངས་འོག་ན་བཞུགས་པ་རྣམས་ནི་རྗེའི་བཀའ་ཉན་ཅིང་ཁྲིམས་ལ་གནས། འབངས་བན་དྷེ་རྣམས་ ༼ཀྱི་༽ འཚོ་བ་བླ་ནས་སྦྱོར། དགེ་བ་བག་ཕེབས་སུ་སྤྱོད། མི་ཡན་ལ་དགྲ་མེད། རྟ་ཡན་ལ་སྒྲོག་མེད། བ་ཡན་ལ་སྣ་མེད། སྟོད་མངའ་རིས་སྐོར་གསུམ་ནས་གསང་འཇལ། མཐའི་སྒོ་བཞི་ནས་དཔྱའ་ ༼དཔྱར་༽ འབུལ། རོང་ཁ་བརྒྱད་ནས་སྐྱེས་རྫོང་། རྒོད་སྟོད་སྡེ་ཞེ་གཉིས་ཐུལ། ཡུ་མོ་སྡེ་བཅུ་གཉིས་ནི་ཉན། བལ་ཡུལ་ཏ་ལ། ཏི། ཀློང་ཡུལ་བྲག་ར། ལི་ཡུལ་འུ་ཐེན། རྒྱ་ཡུལ་སྟན་བཟང་ཡན་ཆད་མངའ་འོག་ཏུ་འདུས། ཁོད་དང་ཁྲིམས་ཐམས་ཅད་མེས་ཀྱི་ལམ་ ༼ལྟར་༽ སྟོན། ལེགས་དགུ་མཁར་དུ་བརྩིགས། སྙན་དགུ་གཏམ་དུ་སྨྲ། དཔའ་མཛངས་ཀྱི་རུ་འབྱེད། མཁས་བཙུན་གྱི་གྲལ་མཚོལ་ ༼མ་འཆོལ་༽ མི་ཉི་མས་སློང་། ཕྱུགས་ནམ་ཟླས་སྡུད། འབངས་ལྷ་རིས་པ་རྣམས་ནི་དཀོན་ཅོག་གསུམ་དུས་སུ་མཆོད། རྗེའི་མངའ་ཐང་ནམ་མཁའི་མཐའ་དང་མཉམ། འབངས་ཀྱི་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཆུ་བོའི་གཞུང་དང་མཚུངས། བོད་རྗེ་འབངས་སྐྱིད་པའི་གཡུང་དྲུང་ཉི་མ་ཤར་བ་བཞིན་དུ་གྱུར་ནས། མི་ལུགས་མཐར་བྱིན། སྟུག་པོ་བཀོད་པའི་ཞིང་ཁམས་འདྲ་སྟེ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དར་ཞིང་རྒྱས་སོ།

Up until that time, an excellent strategy subdued foreign enemies. The royal law (rgyal khrims) was like a golden yoke, heavy in weight; the religious law (chos khrims) was like a silken knot, binding softly; the people's customs (mi chos) were like a straw rope, with many [strands] bound together. The lord above had an exalted attitude, the people below heard the edicts and followed the law (bka’ nyan cing khrims la gnas). The ordinary monks’ livelihoods were treated as important, virtue was readily practised, travellers had no enemies, wandering horses were not ensnared, and cattle were unfettered. From the three regions of Stod mnga' ris, the secret measure;9 from the four border entrances, duty was offered; from the eight valley mouths gifts were sent. The forty-two wild regions of the west (stod) were tamed; the twelve Yu mo districts were obedient. As far as Nepal, Ta la, Ti, the expanse of Brag ra, Khotan (li yul), ’U then, and China, the well-settled regions were brought together under [one] dominion. All arrangements (khod) and laws (khrims) were demonstrably in accordance with to the ancestors’ ways. Everywhere the forts were well-built and speech was pleasant. The brave [soldiers?] were organized into divisions and ranks of the learned were distinguished. People were uplifted by the sun, animals were brought together by the seasons, people and deities worshipped the Three Jewels at [regular] times. The power of the lord was as extensive as the limits of the sky, and his dominion over the subjects (’bangs kyi chab srid) was like the course of a river. Tibet, its lord, and people had become the joyous swastika of a shining sun. The ways of men (mi lugs) were superseded and, like the Gandavyuha buddha-realm, the holy doctrine flourished and developed.

Footnotes:

- Dotson (2006: 69) considers that thul is an area of measurement. ↩

- Dotson (2009: 208) has ‘rebuke slip’. ↩

- Dotson (2009: 208) suggests this is a synonym for yus bdag, indicating a complainant, but these slips also seem to concern actions by the accused, so the more general ‘parties’ is indicated. ↩

- As Dotson (2009: 209) suggests, the na seem to indicate stages in the law-suit, while the phrase zhal lce may indicate the accompanying order. ↩

- shags kyi mgo rgyangs su, literally, ‘fill up the beginning’ of the claim, suggesting provision of the relevant facts. ↩

- In this sentence (mdo lon zhu gcod kyi zhal lce), ‘what is offered and received’ would seem to be a reference to the evidence. Dotson (2006: 259, 263) suggests ‘the law of mDo lon’ and the equivalent passage in Jo sras reads mdo blon zhus bcad, indicating a law made at the request of a minister, mDo blon (see the extract from Jo sras, p. 2). ↩

- dbyangs for dbyang. ↩

- See note 6 above. ↩

- Reading gsang ʼjal as srang ʼjal would suggest some sort of monetary payment. ↩