Chronicles of the dBa’/sBa clan

dBa’/sBa bzhed

Introduction

This group of texts primarily concerns events which took place under Tri Song Detsen (Khri srong lde btsan) (r.742–c.797), including the Samye (bSam yas) debate of the early 790s. They are written from the point of view of the dBa’ (or sBa) clan, but the authors are unknown.

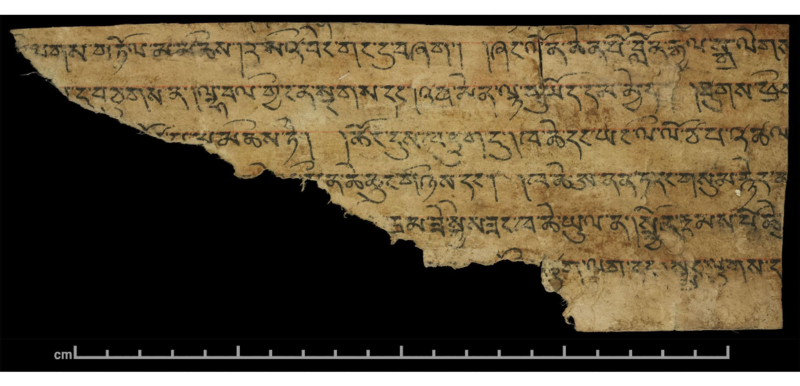

A number of publications exist, containing several different texts. The extracts contained here are from two distinct versions, which have generally come to be known as the dBa’ bzhed and the sBa bzhed, which are the names used here. What seems to be the earliest complete version of the dBa’ bzhed has passages which have been dated to the eleventh century (see Pasang Wangdu and Diemberger 2000). However, the discovery of fragments in the Dunhuang caves containing closely related text suggests that at least the core of the narrative, concerning the events that took place under Tri Song Detsen, dates from no later than the early eleventh century (see van Schaik and Iwao 2008). Whether or not the same is true of the opening section, reproduced here, which describes the creation of law by Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po), is another question.

The text known as the sBa bzhed zhabs brtags ma (the sBa bzhed), primarily concerns events that took place under Tri Song Detsen, including the visit and activities of Padmasambhava. It ends with the activities of Atiśa, meaning that it must have been written after the middle of the eleventh century. Although dealing with similar events, the content is substantially different from that of the dBa' bzhed, including the passages concerning the making of the laws.

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

The following are the sources used for the extracts reproduced here:

- Stein, R.A. 1961. Une chronique ancienne de bSam yas. Paris: Publications de l’Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises [This reproduces a handwritten version of the sBa bzhed, which was created in Lhasa for Hugh Richardson.]

- Pasang Wangdu and Hildegard Diemberger. 2000. dBa’ bzhed: The Royal Narrative Concerning the Bringing of the Buddha’s Doctrine to Tibet. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [This contains photographs of a manuscript held in Lhasa.]

- rBa bzhed phyogs bsgrigs. 2009. Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang [This contains four texts, including the version of the sBa bzhed found in Stein (1961), at pp. 1–79 and a transliteration of the dBa’ bzhed reproduced by Pasang Wangdu and Diemberger (2000), on pp. 237–81.] BBRC: W1KG6259.

References

For a useful discussion of the multiple different versions of the texts, see the blog post by Michael Willis: http://dogankoy.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/notes-arising-from-collation-of-dba.html

Blondeau. 1980. "Analysis of the Biographies of Padma Sambhava according to Tibetan Tradition". In M. Aris and Aung San Suu Kyi (eds) Tibetan Studies in Honour of Hugh Richardson. Warminster: Aris & Philipps, pp. 45–52.

Denwood, Philip. 1990. "Some remarks on the status and dating of the sBa-bzhed". The Tibet Journal XV (6): 135–48.

van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1984. "Miscellanea to a Recent Contribution on the Bsam-yas Debate". Kailash 11/3–4: 149–84.

Macdonald, Ariane. 1971. "Une lecture des P. tib. 1286, 1287, 1038, 1047, et 1290". In Etudes tibétaines dédiées à M. Lalou. Paris: Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient,pp. 283, 288–89, 370–71.

van Schaik, Sam and Kazushi Iwao. 2008. "Two fragments of the Testament of Ba from Dunhuang". Journal of the American Oriental Society 128: 477–87.

Stein, Rolf. 1986. "Tibetica Antiqua IV: La tradition relative au début de bouddhisme au Tibet". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient 75: 169–96.

Sørensen, Per. 1994. The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies: An Annotated Translation of the XIVth Century Tibetan Chronicle. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 633–35.

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1958. Minor Buddhist Texts, II. Rome: Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

dBa'/sBa bzhed extracts

The royal narrative concerning the bringing of the Buddha's doctrine to Tibet

Sangs rgyas kyi chos bod khams su ji ltar byung ba'i bka' mchid kyi yi ge

The text of the dBa’ bzhed used here is the manuscript reproduced in Pasang Wangdu and Diemberger (2000). A transliteration is found in the Beijing edition (2009: 237–81). Folio references and page numbers are to those sources, respectively. The manuscript contains interpolations, which are here indicated by smaller-sized text in brackets.1 The text describes a succession of Tibetan kings, beginning with Lhato Dore Nyentsen (lHa tho do re snyan btsan), followed by Songtsen Gampo (Srong btsan sgam po) (c.600–649), and continuing with later kings. The majority of the text concerns events that took place under Tri Song Detsen.

Extracts

The text begins by stating that it concerns the way in which the holy doctrine (sangs rgyas gyi chos or dam pa’i chos) was introduced into, and established in, Tibet.

[p. 237, fol 1b]

ལྷ་ཐོ་དོ་རེ་སྙན་བཙན་གྱི་སྐུ་རིང་ལ་དབུ་བརྙེས་པ་དེ་ལ་(རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་དྲུག་པ་མ་ཎི་པད་མེ་གསེར་ལས་བྲིས་པ་སྒྲོམ་བུ་བཅུག་ནས་ནམ་མཁའ་ལས་མངའ་བདག་གི་དྲུང་དུ་བབས་པ་ཆོས་དང་། བོན་དུ་ངོ་མ་ཤེས་ཏེ་) དེ་ལ་གཉན་པོ་གསང་བ་ཞེས་མིང་བཏགས་ཏེ་གཡུ་(སྔ་ཟེར་ཏེ་ནས་ཡིན་) མངོན་དང་གསེར་སྐྱེམས་ཀྱིས་མཆོད། ཡུན་བུ་གླ་སྒང་གཉན་གྱི་མཛོད་དུ་སྦས་ཏེ་བཙན་པོ་ཉིད་ཀྱང་དུས་དུས་སུ་ཞལ་ཕྱེ་ཞིང་གཟིགས། ཞལ་ཆེམས་སུའང་ངའི་དབོན་སྲས་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཆེ་ན་ཡང་འདི་ཞལ་ཕྱེ། ཆབ་སྲིད་ཆུང་ནའང་འདི་ཞལ་ཕྱེ་ཤིག་ཅེས་བཀའ་བསྩལ་ཏོ།

As far as the first appearance at the time of Lha tho do re snyan btsan is concerned, (the six syllables of India, Ma ṇi pad me, written in gold and contained in a casket, fell from heaven in front of the king. Without knowing whether this was Buddhist or Bon) this was named ‘the mysterious power’ (gnyan po gsang ba). Then g.yu mngon (called snga, a kind of barley) and a ritual libation was offered to it. While it was in the treasury of Yun bu gla sgang, the king would open it from time to time and study it. In a testament, he proclaimed, ‘May my descendants open it, whether the kingdom prospers or declines’.

[p. 237, fol. 1b]

དབོན་སྲས་ཀྱི་སྐུ་རིང་ལ་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཆེ་རབ་ཏུ་གྱུར་ཏེ། གཉན་པོ་གསང་བ་ཞལ་ཕྱེ་བ་ལས་ཟ་མ་ཏོག་གི་སྙིང་པོ་ཡི་གེ་དྲུག་པ་རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་གསེར་གྱིས་ ... བྲིས་པ་ཅིག་དང་མུ་ཏྲའི་ཕྱག་རྒྱ་(གཙུག་ཏོར་དྲི་མེད་) ཅིག་བྱུང་ངོ་།

During the reign of his descendants, the kingdom expanded greatly and, after the powerful secret had been opened, the za ma tog with six essential syllables, written in gold Indian letters, and the mu tra’i phyag rgya (the gtsug tor dri med) appeared.

[p. 237–38, fol. 1b–2a]

དེ་ནས་བཙན་པོ་ཁྲི་སྲོང་བཙན་གྱི་སྐུ་རིང་ལ་བལ་རྗེའི་བུ་མོ་(ཁྲི་བཙུན་) ཁབ་ཏུ་བཞེས་ནས་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་ར་ས་པེ་ཧར་གླིང་བརྩིགས། གཞན་ཡང་རུ་བཞིའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་(༤བཅུ་རྩ་གཉིས་) བཞེངས་སུ་གསོལ། བྲག་ལྷ་བགྱིས། རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་ཆོས་དང་ཡི་གེའི་དཔེ་ལེན་པར་འཐོན་མི་གསམ་པོ་ར་ལ་བཀའ་སྩལ་ཏེ་བཏང་ནས། ཡིག་མཁན་རྒྱ་གར་ལི་བྱིན་ཞེས་བགྱི་བ་ཞིག་ཀྱང་ཁྲིད་དེ་མཆིས། ཆོས་དཀོན་མཆོག་སྤྲིན་དང་། (པད་མ་དཀར་པོ། རིན་པོ་ཆེ་ཏོག གཟུགས་གྲྭ་ལྔ་དང།) དགེ་བ་བཅུ་བཙལ་ནས་མཆིས་ཏེ། ཆོས་ནི་ཕྱིང་པའི་ཕྱག་མཛོད་དུ་ཕྱག་རྒྱས་སྩལ་ཏེ་བཞག་ནས། ངའི་གདུང་རྒྱུད་ལས་དབོན་སྲས་ཀྱི་མི་རབས་ལྔ་ན་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་ཆོས་རྒྱས་པར་བྱེད་པ་ཅིག་འབྱུང་གིས་དེའི་ཚེ་སྒྲོམ་བུ་འདི་ཁ་ཕྱེ་ཅིག་ཅེས་བཀའ་སྩལ་ཏེ། (ཡི་གེ་ནི་ལི་བྱིན་དང་གསམ་པོ་རས་རྒྱ་ཡིག་བོད་ཡིག་ཏུ་བསྒྱུར།) ཞ་འབྲིང་ནང་པ་བཞི་ལ་བསླབས།

During the reign of Khri srong btsan, after his marriage with the daughter of the king of Nepal (Khri btsun), the Lhasa temple (Ra sa pe har gling) was built. The construction of the (forty two) temples of the Ru bzhi was requested and the Brag lha temple was built. ’Thon mi gsam po ra was sent by royal order [to India] in order to acquire the Indian doctrine and a model for the alphabet. He returned with Li byin, an Indian skilled in reading and writing, and brought with him some texts of the doctrine, such as Chos dkon mchog sprin, (Pad ma dkar po, Rin po che tog,

gZugs (gzugs) grwa lnga), and the ten virtues (dge ba bcu). The texts of the doctrine were given the royal seal and placed in the treasury of Phying pa [castle]. Then [the king] announced, ‘In my lineage, after five generations there will be a descendant who will spread the doctrine of the Buddha and at that time the casket should be opened.’ (As far as the alphabet was concerned, Li byin and gSam po ra transformed the Indian script into the Tibetan script). It was taught to four attendants in charge of the royal household.

[p. 238, fol. 2a]

དེའི་(ཚེ་) རྒྱལ་པོ་ཕོ་བྲང་ན་བཞུགས་ཏེ་དགུང་ལོ་བཞིའི་བར་དུ་ཆབ་སྒོར་ཡང་མ་གཤེགས་(མཚམས་མཛད་) པ་དང་། འབངས་ཀུན་གྱི་མཆིད་ནས་བཙན་པོ་ནི་ཕོ་བྲང་སྒོར་ཡང་མི་གཤེགས་ཏེ་ཅིའི་ཆ་ཡང་མེད་པ་ཞིག་བློན་པོ་ནི་འཛངས་པ་ཞིག་གོ་ཞེས་འབངས་བྱིན་གྱིས་གཡར་ནས་གླེངས་ཞེས་བཙན་པོའི་སྙན་དུ་གདས་ནས། ཞ་འབྲིང་ནང་པ་ཡི་གེ་བསླབ་(པ་) བཞི་དང་མོལ་ཏེ། བཙན་པོས་དགོངས་ནས་ཟླ་བ་བཞིའི་བར་དུ་(སྲོག་གཅོད་ཡང་བའི་ཕྱིར་སྟོང་གསོས། རྐུ་འཕྲོག་ཡང་བའི་ཕྱིར་རྐུ་འཇལ། ལོག་གཡེམ་སྤང་བའི་ཕྱིར་སྣ་མིག་གམ་ཆལ། བརྫུན་མནའ་བའི་ཕྱིར་སྤང་པ་སོགས་) བཀའཁྲིམས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལས་གཞི་བླངས་པ་ཞིག་མཛད་དེ་ཡི་གེ་བྲིས་སོ།།

At that time the king remained in his palace, (in retreat), without even coming to the gate, for four years. All the subjects said, ‘The king does not even come to the gate of the palace; whatever the reason, he seems to have disappeared; there appears to be a minister ruling instead.’ The king heard these rumours from the subjects. He therefore held a discussion with his four attendants—those who had been taught the alphabet in four months—and, on the basis of the ten virtues, he made the law (bka’ khrims) and set it down in writing. (It made provisions for blood money (stong gsos) for the taking of human life, compensation (rku ’jal) for theft and robbery, cutting off noses and removing eyes for sexual misconduct, taking oaths for detecting lying, and so on).

[p. 238–39, fol. 2a–2b]

དེ་ནས་ནང་ཅིག་འབངས་ཀུན་བསོགས་ཏེ་བཀའ་སྩལ་པ། ངས་ཕོ་བྲང་འཕོ་སྐྱས་མ་བྱས་པར་མལ་༡ན་འདུག་སྟེ་བྱ་བ་བསྐྱུངས་ཏེ་འབངས་རྣམས་དལ་ཞིང་སྐྱིད་པར་འདུག་པ་ལས། ཁྱེད་ན་རེ་བཙན་པོ་ནི་ཕོ་བྲང་སྒོར་ཡང་མི་གཤེགས་ཅིའི་ཆ་ཡང་མེད་པ་ཞིག བློན་པོ་ནི་འཛངས་པ་ཞིག་ཟེར་བ་བློན་པོ་འཛངས་པ་ངས་བསྐོས་སམ་ཁྱེད་ཀྱིས་བསྐོས་པ་ཡིན། དེ་ལྟར་འབངས་ཁྱེད་མི་དགའ་ན། ངས་ཟླ་བ་བཞིར་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་པ་ཞིག་ཡོད་ཀྱིས་དེ་བཞིན་དུ་གྱིས་ཤིག དེ་ལྟར་མ་བྱས་ན་ད་ལྟར་རྒྱལ་ཕྲན་བཅུ་༢སྲིད་ཁྱམས་པ་ཡང་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་མེད་པ་ལས་གྱུར་པས། ཕྱི་རྗེས་སུ་ཉེས་པ་མང་བར་འགྱུར་ཞིང་། ངའི་དབོན་སྲས་རྗེ་འབངས་ཁྲིམས་སྲིད་ཀྱང་མེད་པར་འགྱུར་བས་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་བཙན་པར་གྱིས་ཤིག་ཅེས་བཀའ་སྩལ་ཏོ།

One day, the king ordered all the subjects to gather and announced, ‘I have been staying in one place without moving the royal residence. I have avoided dealing with affairs and the subjects have been relaxed and happy. You have noticed that the king has not even come to the gate of the palace and that, whatever the reason, he seems to have disappeared, and that there has been a minister ruling instead. Was the wise minister appointed by you or by me? If you, subjects, do not like this, you must act according to a law (bka’ khrims) which I made in four months. If you do not follow it, [the kingdom] will become like the twelve petty kingdoms, which lost political power because they had no law. After that, crimes will increase and my descendants, king and subjects, will not have a legal government (khrims srid). So you must follow the law carefully.’

[p. 239, fol. 2b]

བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་དང་བཀའ་ནན་གྱིས་རྩིས་མགོ་དང་ཆོས་ལུགས་བཟང་པོ་རིལ་མ་ནོར་བར་སྔ་དྲོ་ཐོག་ཐག་འབངས་འཚོགས་པ་ལ་བཀའ་ཞལ་གྱིས་སྩལ་ཏོ། དེ་ནས་འབངས་ཡོངས་ཀྱིས་གཏང་རག་བཏང་སྟེ། བཙན་པོ་ཁྱོད་ལས་བསྒམ་པ་མི་བཞུགས་པས་མཚན་ཡང་ཁྲི་སྲོང་བཙན་བསྒམ་པོ་ཞེས་བགྱིའོ་ཞེས་འབངས་ཀྱིས་མཚན་གསོལ་ཏོ།

For a whole morning the whole administrative record (rtsis mgo) and all the good customs (chos lugs bzang po) (made) in accordance with the law and the official orders (bka’ nan) were announced to the assembled subjects, without any mistakes. Then all the subjects offered thanks and said, ‘Since no-one is more profound than you, you shall be called Khri srong btsan bsgam po’.

The text continues with an account of the mission sent by Songtsen Gampo to the emperor of China to seek his daughter as a bride, and her bringing a Śākyamuni statue to Tibet. It then continues with the following story.

[pp. 240, fols 3a–3b]

མི་རྣམས་ནི་བཙན་པོ་ཁྲི་སྲོང་བཙན་ཨརྱ་པ་ལོ་ལགས་སོ་ཞེས་མཆི་སྟེ། དེ་ལྟར་ཅི་མངོན་ཞེ་ན། སངས་རྒྱས་མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་ནས་ལོ་བརྒྱ་ན་ལི་ཡུལ་དུ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་འབྱུང་། དེའི་ཚེ་ལིའི་བན་དེ་༢ཀྱིས་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་མཐོང་བར་འཚལ་ཏེ། དགུང་ལོར་མཆོད་པ་དང་བསྙེན་པ་བགྱིས་པ་ལས། འཕགས་པ་འཇམ་དཔལ་བྱོན་ནས་རིགས་ཀྱི་བུ་དག་ཅི་འདོད་ཅེས་གསུང་ནས། བདག་ཅག་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་མཐོང་བར་འཚལ་ལོ་ཞེས་གསོལ་པ་དང་། བཀའ་སྩལ་པ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཡིན་པས་བོད་ཡུལ་དུ་སོང་ཤིག་ཞལ་མཐོང་བར་འགྱུར་རོ་ཞེས་གསུང་ནས། མོད་ལ་གསེག་ཤང་རེ་རེ་ཐོགས་ནས་ཡས་ཀྱིས་མཆིས་ཏེ་བོད་ཡུལ་བཙན་པོའི་ཕོ་བྲང་དུ་མཆིས་ན།

People considered King Khri srong btsan to be Āryā Palo. This can be related as follows. The holy doctrine had arrived in Li (Khotan) one hundred years after the nirvana of the Buddha. At that time two monks of Li longed to see the face of ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs and they were making offerings and propitiations throughout the year. ’Phags pa ’jam dpal appeared and asked, ‘Blessed sons, what do you need?’ They replied, ‘we are longing to see the face of ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs’. ’Phags pa ’jam dpal replied, ‘’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs is the king of Tibet; go to Tibet and you will see his face’. Then, carrying sūtras and monks’ staves they travelled from the upper regions to the royal palace in Tibet.

[p. 240–41, fol. 3b]

བཙན་པོའི་བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་དང་པོ་འཆའ་བའི་དུས་སུ་ཕྱིན་ཏེ་ལ་ལ་ནི་བཀུམ། ལ་ལ་ནི་སྤྱུགས། ལ་ལ་ནི་བཟུང་ནས་ཚེར་ཐགས་སུ་སྩལ། ལ་ལ་ནི་སྣ་མིག་ལ་ཕབ་པ་མཐོང་སྟེ། ལི་བན་དེ་༢ལ་མ་དད་པར་གྱུར་ཏེ་འདི་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཅང་མ་ཡིན་པས་སླར་འདོང་ཞེས་རང་ཡུལ་དུ་འགྲོ་བར་བགྱིས་པ་ལས། བཙན་པོས་དེ་མཁྱེན་ནས་བཀའ་ལུང་སྩལ་ཏེ་ཕོ་བྲང་གི་ཆབ་སྒོ་བཞི་ནས་བན་དེ་༢ ལ་བོས་ནས་བཙན་པོའི་བཀའ་ཞལ་(ནས་) ཕོ་བྲང་གི་ནང་དུ་སྤྱན་སྔར་མཆི་ཞེས་ནང་དུ་བཀུག་ནས་སྤྱན་སྔར་ཕྱག་འཚལ་བ་དང་། ཁྱེད་འདིར་ཅི་ལ་འོངས་ཤེས་བཀས་རྨས་པ་དང་། བདག་ཅག་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་མཐོང་བར་འཚལ་ཏེ་འདིར་མཆིས་པ་ལགས་ཅེས་གསོལ་པ་དང་། བཙན་པོ་བཞེངས་ནས་འདོད་ཞེས་གསུངས་པ་དང་། ལི་བན་དེ་༢ཁྲིད་དེ་གཤེགས་ནས་ཐང་དབེན་པ་ཞིག་ཏུ་བྱོན་ནས་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་སྐུ་བསྟན་པ་དང། དེ་༢དགའ་སྟེ་ཕྱག་འཚལ་བ་དང་། ད་ཁྱེད་ཅི་འདོད་ཅེས་བཀའ་སྩལ་པ་ན་བདག་ཅག་སླར་ལིའི་ཡུལ་དུ་ཕྱིན་པར་འཚལ་ལོ་ཞེས་གསོལ་པ་དང་། བཙན་པོའི་ཞབས་ལ་བཟུང་སྟེ་ངུས་ནས་ཕོ་བྲང་དུ་གཉིད་ལོག་སྟེ་འདུག་པ་དང་ལྡན་པ་ལ་ཉི་མ་དྲོ་བགྱིད་དེ་སད་པ་དང་འཕགས་པ་ནི་མི་བཞུགས་བན་དེ་༢ནི་ལི་ཡུལ་ན་མཆིས་ནས་གདའ་།

At this time the first law (bka’ khrims) of the king was being enforced. They saw some people being executed, some sent into exile, some imprisoned inside an enclosure of thorns, others had their noses cut off or their eyes removed. The two monks of Li lost their faith and said, ‘this cannot be ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs; let us go back’. They were about to set off for their country when the king learned of them. An order was issued [for attendants] to go out from the four gates of the palace to summon the two monks. After they arrived, they prostrated before the king and he asked, ‘Why have you come here?’ They replied, ‘We came here because we were longing to see the face of ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs.’ The king stood up and said, ‘Let us go’. He took the two monks to a wide, lonely plain and he showed them the form of ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs. The two monks were delighted and prostrated. Then he asked them, ‘Now what do you wish to do?’ They replied, ‘We beg you to let us return to Li.’ They clutched the feet of the king and cried. Afterwards they fell asleep in the palace. A warm sunshine woke them up. ’Phags pa had disappeared and the two monks were back in Li.

[p. 241, fol. 3b-4a]

སྔར་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་མ་ལགས་སྙམ་ནས་སླར་ལི་ཡུལ་དུ་འགྲོ་བ་འབའ་ཞིག་སེམས་པ་བལྟས་ནས་དངོས་གྲུབ་གཞན་མ་སྤོབས་པ་ལས་། ཐེ་ཚོམ་མ་མཆིས་པར་འཕགས་པ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ལགས་ངེས་ཟེར་རོ། ལུང་བསྟན་ཆེན་པོ་ལས་ཀྱང་ལེགས་པར་འབྱུང་ངོ་།

They said that before, when they had thought that it was not ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs and they were clinging to the idea of returning to Li, they were not able to obtain supernatural realization. However, the king was ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs, beyond any doubt. This is reported from the great prophecy of Li yul.

The text continues with short accounts of the activities of the kings Dusong (‘Dus srong) and Tri Detsugten (Khri lde gtsug btsan), before moving on to the reign of Tri Song Detsen, which forms the major part of the text.

There is considerable opposition to the king’s attempts to support Buddhism in Tibet, but he is supported by gSas snang of the dBa’ clan.

[p. 258, fol. 15a]

དེ་ནས་གསས་སྣང་གིས་བླའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་མ་བརྩིགས་པར་གླག་གི་ལྷ་ཁང་བཞེངས་སུ་གསོལ། དབའ་ཕ་ཚན་བོན་བཞག་ནས་ཆོས་བགྱིད་དུ་སྩལ། དབའ་ལྷ་གཟིགས་ཀྱིས་གྲོགས་པོ་མྱང་རོས་ཀོང་གི་དགེ་བའི་བཤེས་གཉེན་བྱས། ཆོས་བསླབ(ས)་ཁྲིམས་ལྔ་ཕོག རོས་གོང་གིས་ཀྱང་ཕུ་ནུ་བོའི་དགེ་བའི་བཤེས་གཉེན་བྱས་ཏེ་དཀར་པོར་བསྒྱུར་རོ། དེ་ནས་ཡོས་བུའི་ལོ་ལ་བསམ་ཡས་རྩིག་པར་བཅད་དེ།

Then, as gSas snang had not built the bLa temple he commissioned the gLag temple. [He] asked the male members of the dBa’ clan to abandon Bön and adopt the practice of Buddhism (chos). dBa’ Lha gzigs became the spiritual guide of his friend Myang Ros Kong. He gave [him] the five Buddhist precepts (chos bslab khrims). Ros Khong, in turn, became spiritual guide of his male relatives and made them virtuous. Then, in the male hare year [763 or 775] they decided to build bSam yas [monastery].

Following the great debate concerning Buddhism and Bon and the building of Samye monastery, members of ministerial families are sent to India to learn the language of the doctrine. A great consecration of the Samye temple is held, at which one hundred people take monastic vows.

[p. 262, fol. 17b]

བཀའ་ཤོག་ཆེན་པོ་བཏང་། སླན་ཆད་ཆགས་(ཆབ་) འོག་གི་འབངས་ལ་ཕོ་མིག་མི་དབྱུང་། མོ་སྣ་མི་གཅད་པར་གནང་། འབངས་ཕྱོགས་སུ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་བཀའ་(དྲིན་) ཆེན་པོ་སྩལ་བར་བཀས་གནང་། བློན་ཆེ་མན་ཆད་སྣ་ལ་གཏོགས་པ་འབངས་རིལ་པོས་(གྲོས་འཚལ་ཆོས་གཙིགས་མཛད་དེ་རྡོ་རིངས་བཙུགས།)

A great bka’ shog was promulgated: henceforth, among his subjects, men’s eyes were not to be put out, women’s noses were not to be cut, and the great (kindness) of religious doctrine was to be bestowed on the subjects. Everyone, from the higher and lesser ministers to the subjects, (was consulted, edicts (chos gtsigs) were recorded, and a pillar was erected).

The text continues by recording the material support to be provided for the sangha and their institutions.

The text announces its end with the death of Yeshe Wangpo (Ye shes dbang po), the first abbot of Samye, but continues with a short paragraph on Tri Tsug Detsen (Khri gtsug lde btsan), or Ralpachan. Indian scholars were invited, translations were made, and one hundred and eight temples were completed.

[p. 274, fol. 25b]

ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དར་གྱི་མདུད་པའང་བསྐྱར་ནས་བསྡམས་ཏེ་ལྷ་ཆོས་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་པོ་།

The religious law (chos khrims) was tied again, like a silken knot, and the holy doctrine (lha chos) was securely established.

This is the conclusion of the main part of the text. It continues, in this manuscript, in a different hand, with events under subsequent kings.

Under the young King Muné Tsenpo (Mu ne btsan po) there is a debate among religious leaders concerning funerary rituals. A minister on the side of the Bonpos gives an account of the past and the establishment of a powerful kingdom. In response, Vairocana (Be be ro tsa na) addresses the king:

[p. 277, fol. 28a]

ཨུམ་བྱང་ཆུབ་སེམས་དཔའི་གདུང་རྒྱུད། རིགས་གསུམ་མགོན་པོའི་སྤྲུལ་པ། ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེན་པོའི་མངའ་བདག མི་རྗེ་ལྷའི་དབོན་སྲས། རིན་པོ་ཆེ་གསེར་གྱི་གཉའ་ཤིང་ལྟ་བུ་དབུ་ལ་བཞུགས་ལགས།

‘From the lineage of the bodhisattvas, emanation of the three protectors, lord of great compassion, you are the lord of the people and the descendant of the gods. You will remain at the top, like a precious golden yoke.’

Footnotes:

- Occasional edits are marked as normal-sized text, within brackets. ↩

The supplemented testament of sBa on the activities concerning sūtra and tantra during the period of Emperor Khri srong lde btsan and learned master Padma

bTsan po Khri srong lde btsan dang mkhan po slob dpon Pad ma'i dus mdo sngags so sor mdzad pa'i sba bzhed zhabs btags ma

The narrative begins shortly before the birth of Tri Song Detsen and recounts numerous struggles between those promoting and opposing the Buddhist religion and its monuments. The activities of gSal snang, minister of the sBa clan and supporter of Buddhism, are prominent. Śāntarakṣita and Padmasambhava are invited to Tibet. After the defeat of the Bönpo, the construction of the temple of Samye (bSam yas) is initiated. On completion of the temple the first Tibetan monks are ordained. Although some ministers object to the new ordinations, the king promises to provide for the needs of the monks. Two queens and 300 people adopt the religion. At this point the king makes laws. He elevates the monks above the laity. The text continues with political and diplomatic events, which include further opposition to Buddhism, and it recounts the complicated events that follow the death of the king.

Extracts

(The Tibetan text and page numbers are reproduced from the Beijing edition (2009: 1–79)).

During the infancy of Tri Song Detsen and after the death of his father, there are conflicts over the new religion.

[p. 6-7]

རྒྱལ་བུ་སྐུ་ནར་མ་སོན་པས། བློན་ནག་པོ་ལ་དགའ་བས་ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་བཅས་ནས་ཆོས་གཤིག

As the prince had fallen ill, malevolent ministers established minor laws and destroyed the dharma.

[p. 8]

དེའི་དུས་སུ་ཡུལ་ངན་ཆེན་མོ་བྱུང་ནས། འབངས་གུམ་པ་ལ་ཚེ་བགྱིར་མ་གནང་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་བཅས་པའི་འོག་ཏུ་བ་ལམ་རླགས་ན་སྦ་གསལ་སྣང་གི་བུ་ཚ་མིང་སྲིང་གཅིག་དུས་གཅིག་ལ་གུམ།

At that time, great calamity befell the country. As for the death of the subjects, in the destructive path under the minor laws—which did not preserve life—the children (brother and sister) of sBa gsal gnang died at the same time.

Three translators are employed by Tri Song Detsen and they are threatened by the ministers sTag ra and Zhang ma zhang. They say:

[p. 10]

ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་ལས་ཆོས་བྱས་ཕོ་རང་དུ་གཏན་སྤྱུག་པ་མ་ཐོས་སམ།

Have you not heard that Buddhist practitioners and bachelors are to be completely banished under the minor laws?

The Bönpo have been defeated and it is decided to limit their activities and to encourage Buddhism. The statue of Sakyamuni is brought back to the Ra mo che and the foundations of Samye are laid.

[p. 25]

ཡོས་བུ་ལོའི་དཔྱིད་བསམ་ཡས་ཀྱི་རྨང་འདིངས་པར་ཆད་ཙ་ན། གསལ་སྣང་གིས་སྔོན་དུ་གླག་མདའི་ལྷ་ཁང་རྩིགས་ནས་སྦ་བ་ཚན་ཆོས་ལ་བཀོད། འབའ་ལྷ་གཟིགས་ཀྱིས་མྱང་རོས་ཀོང་ལ་དགེ་བའི་བཤེས་གཉེན་བྱས། ཁྲིམས་རྔ་༼ལྔ་༽ ཕོག་མྱང་རིགས་དཀར་པོར་བཏང་།

In the spring of the male hare year [763 or 775], they decided to lay the foundations of Samye. First, gSal snang built the gLag mda’ temple, and the sBa clan were established in the dharma. ’Ba’ Lha gzigs became spiritual guide of Myang Ro Kong. He bestowed the five rules1 and guided the Myang family towards virtue.

There is a meeting of the king, with his ministers, in order to discuss the construction of Samye monastery, which is opposed by some.

[p. 26]

རྗེའི་བཀའ་གཉན་པས། བཀའ་ཁྲིམས་དང་བཀའ་ནན་དྲགས་ཏུ་གསལ་བར་འདེམ་ཀ་བོར་བ་སོགས་པ་ལྐོག་ཏུ་ཆད་ནས། བོད་འབངས་ཀུན་ཚོགས་ཏེ་བཀའ་སྩལ་པ། འཛམ་གླིང་ན་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་མི་ཆེ། བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ང་ལས་ཆེ་བ་ནི་སྔར་མ་བྱུང་། ང་ལས་ཕྱག་རིས་མེད་པ། ཕྱག་རི་ཞིག་བྱེད་པས། ཁྱོད་བོད་འབངས་འཛངས་པ་རྣམས་གླེང་ཅེས་པ་གསུངས། བློན་པོ་ཁྲི་བཟང་ལངས་ནས། རྗེའི་བཀའ་སྩལ་ནི་བདུད་པས་གཉན༼ཉན༽། །ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་ལ་རྩེ་ནི་གུང་ལས་མཐོ། ཕྱག་རྗེས་གང་མཛད་པ་བཀའ་ལུང་ཞུའོ་མཆི།

In a stern speech, the lord said, ‘The firm and explicit edicts and commands (bka’ khrims dang bka’ nan), which eliminate choice, have been secretly ignored. All the Tibetan people have been gathered and given orders (bka’ stsal). The kings of Tibet are great men in this world, but there has never been a king of Tibet greater than me. Mine are the only [important] written documents (phyag ris). Since I have written a document, you—the learned people of Tibet—should discuss it’. Minister Khri bzang got up and said, ‘The order (bka’ stsal) of the lord is heard2 by the demons and the peak of the law is higher than the heavens. Whatever the lord writes, please proclaim it orally (bka’ lung)’.

The text describes the layout of Samye.

[p. 34]

དང་པོ་རྣམ་དག་ཁྲིམས་ཁང་གླིང་ཟླ་གམ་དུ་བྱས་ཏེ།

First, a complete law building was built in the semi-circular area.

After the consecration of Samye and the promotion of teachings, the first monks are ordained, although some ministers object. The king promises to support the monasteries. Two queens and three hundred people take vows.

[p.45]

བཀའ་ཤོ་ཆེན་པོ་བྱུང་ཆོས་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས། དེ་ནས་ཕོ་མིག་མི་དབྱུང་བ་དང་། མོ་སྣ་མི་བཅད་པ། མཚང་ཅན་མི་ཀུམ་པ། སྐྱེ་བོ་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱིས་རྗེའི་བཀའ་ཉན་པ། རྗེ་འབངས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱིས་རབ་ཏུ་བྱུང་བ་དབུར་ཕྱུང་ལ་ཕྱག་དང་མཆོད་གནས་བྱ་བ། དེ་ལྟར་བྱ་བའི་ཆེད་དུ་བཙན་པོ་ཡབ་སྲས་དང་། སྣ་ཆེན་པོ་མ་གཏོགས་པས་བྲོ་བོར་རོ།།

[Khri srong lde btsan] made a great legal edict (bka’ sho) and religious laws (chos kyi khrims), according to which men’s eyes were not to be put out, women’s noses were not to be cut, and wrong-doers were not to be killed. All people were to be obedient to the king. Those among the lords and subjects who were ordained as monks were to be placed at the head to be venerated and offerings were to be made [to them]. The men of the king’s family and the high ministers took an oath that they would ensure that these things happened.

After Tri Song Detsen dies, his youngest son is considered to be too young to govern, so interim measures are put in place.

[p. 59]

བློན་འཛངས་པ་བསྐོས་ལ་ཁྲིམས་བུ་ཆུང་བཅའོ་མཆི།

A wise minister was appointed and told to establish the minor laws.

There is further discontent under the later king, Ralpachan (Khri gtsug lde btsan)

[p. 66–67]

དཀོན་མཆོག་བརྒྱད་ཅུ་འཇལ་བཅད་པ་ལ་སོགས་པའི་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མཛད་པས། ཞང་བློན་ནག་པོ་ལ་དགའ་པ་རྣམས་གྲོས་བྱས་ནས་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་གཤིག་པའི་ལྐོག་གྲོས་བྱས་ནས། དེ་ལ་སྔོན་དུ་བཙན་པོ་མ་སྐྲོངས་ན་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་མི་ཤིག་ཟེར།

The religious law (chos khrims) was created in accordance with the decisions of the eighty rare and supreme ones (dkon mchog). The Zhang ministers, who were inclined to evil, conferred and had a secret discussion about destroying the religious law. ‘For that to happen’, they said, ‘we must kill the emperor, or we will not destroy the religious law.’