The Mirror of the Two Laws

Khrims gnyis gsal ba'i me long

Source and Dating

The source of this transliteration and translation is the handwritten compilation known as the Tibetan Legal Materials, currently held at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives at Dharamsala. This is the earliest known version of this text. It must date from at least the mid seventeenth-century, given the dates of the other texts included in the compilation. Modern printed editions differ in small, and generally similar, ways from the text presented here. Many of the differences appear to be transcription errors.

Historical Context

In its colophon, the text describes itself as the Khrims gnyis lta ba'i me long, the Mirror of the Two Laws, but the author(s) and the date and context of its creation are not given. Pejorative references to Mongol laws, in the section on killing, indicate that the text was written after the end of the Mongols' domination of Tibet in 1368. The colophon also refers to edicts by the Phakmodru (Phag mo 'gru) leader, Jangchub Gyaltsen (Ta'i si tu Byang chub rgyal mtshan), indicating that it was written by or for someone of this lineage, although not Jangchub Gyaltsen, himself, who died in 1364.

Khrims gnyis lta ba’i me long, LTWA, p. 19.

Further Reading

For further analysis of the text, see:

- Manson, Charles, and Fernanda Pirie. 2023. "The Earliest Tibetan Legal Treatise: The Khrims gnyis lta ba’i me long". In A Life in Tibetan Studies: Festschrift for Dieter Schuh at the Occasion of His 80th Birthday, edited by Christoph Cüppers, Karl-Heinz Everding, and Peter Schwieger, 483–522. Lumbini: LIRI.

- Pirie, Fernanda. 2020b. "The Making of Tibetan Law: The Khrims gnyis lta ba’i me long". In On a Day of a Month of a Fire Bird Year, edited by Jeannine Bischoff, Petra H. Maurer, and Charles Ramble, 599–617. Lumbini: LIRI.

Sources

Khrims gnyis lta ba’i me long. Reproduced in Tibetan Legal Materials. 1985. Dharamsala: The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, pp. 3–38. [BDRC: W23704]

———. Bod kyi snga rabs khrims srol yig cha bdams bsgrigs. 1989. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, 46–81. [Reprinted in 2011, 49–86].

———. sNga rabs bod kyi srid khrims. 2004. bSod nams tshe ring (ed.) Beijing: Mi rigs, dpe skrun khang. [Reprinted in 2010, 130–63].

———. sNga rabs bod kyi srid khrims gsal ba’i me long. 2014. bSod nams tshe ring (ed.) Beijing: Mi rigs, dpe skrun khang, 190–226.

References

Goldstein, Melvyn. 2001. New Tibetan-English Dictionary of Modern Tibetan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jäschke, H. 1881. A Tibetan-English Dictionary. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Rangjung Yeshe Wiki, Dharma Dictionary: http://rywiki.tsadra.org/index.php?title=Main_Page&oldid=449112

Tibetan and Himalayan Library, Tibetan Dictionary Project: http://www.thlib.org/reference/dictionaries/tibetan-dictionary/

The translation

This, very preliminary, translation has been prepared by Fernanda Pirie and Charles Manson. The transcription follows the manuscript copy known as Tibetan Legal Materials. Alternative readings are indicated in round brackets; the page numbers corresponding to the manuscript are indicated in square brackets. Occasionally these are suggested by later editions of the text. The translators received invaluable advice from Professor Dieter Schuh, who devoted several days to the patient examination of the more difficult parts of the text. The late Tsering Gonkatsang, University of Oxford, was also generous with his advice on knotty grammatical problems. Yannick Laurent spent many hours on the transliteration. The translators are grateful to all three. Errors remain their own.

A great many uncertainties remain about the translation, which should be regarded as a first draft, rather than a definitive version. The translators hope that it will, nevertheless, be useful to other scholars and would welcome comments and corrections.

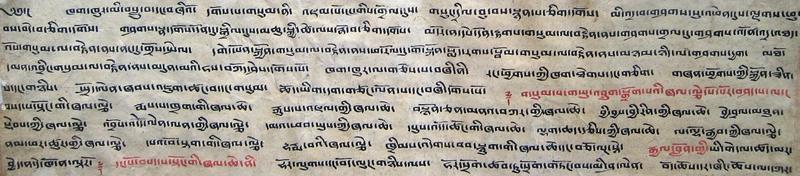

Manuscript facsimile

Jump to:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Colophon

(To see a footnote's contents, hover over it or click it)

༄༅ ། བརྒྱད་ཁྲི་བཞི་སྟོང་དམ་ཆོས་ཕུང་པ་ཆེ།

ལུང་རྟོགས་རྒྱ་མཚོའི་དབུས་ན་ལྷུན་ཆགས་ཤིང་།

ཕུན་ཚོགས་རིན་ཆེན་ལས་གྲུབ་བང་རིམ་མཐོ།

སྡེ་སྣོད་ཉི་ཟླའི་རྣ་ཆས་སྤ་དེར་འདུད།

ཇི་ལྟ་ཇི་སྙེད་ནང་གི་ཡེ་ཤེས་ཏེ།

རིག་གྲོལ་སྨྲ་བ་ཕྱིར་མི་ལྡོག་པའི་ཚོགས།

བླ་མེད་ཡོན་ཏན་ཀུན་ལྡན་དཔལ་གྱི་གཞི།

འཕགས་མཆོག་དགེ་འདུན་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་དགེ་ལེགས་སྩོལ།

ཞེས་དཔལ་མཆོག་གི་རྒྱུད་དང་། རྡོ་རྗེ་གུར་དང་། སངས་རྒྱས་མཉམ་སྦྱོར་སོགས་ནས་གསུང་པའི་དཀོན་མཆོག་གསུམ་གྱི་ཤིས་པ་མརྗིད(བརྗིད)་པའི་ཚིགས་སུ་བཅད་པ་སྔོན་དུ་བཏང་ནས། དེ་ཡང་།

The great collection of the holy doctrine in 84,000 [texts] [is]

The majestic Mount Meru, in the midst of an ocean of transmission and realization,

With high terraces made of the most precious jewels,

To the collection of (piṭaka) scriptures ornamented with sun and moon, I bow.

Whatever [the texts] are, and however many there may be, the wisdom within them

Expounds awareness and liberation; consequently the multitude of non-returners

Endowed with all peerless qualities, will form the basis of the glorious ones,

The Noble Sangha, who bestow wondrous virtue.

These are presented as preliminary verses on the splendid goodness of the Three Jewels, quoted from the dPal mchog gi rgyud,1 the rDo rje gur,2 and the Sangs rgyas mnyam sbyor, and so forth.

དང་པོ་ནི།

Firstly

བཅོམ་ལྡན་ལས་(འདས)་གཉན་ཡོད་ན་རྒྱལ་བུ་རྒྱལ་བྱེད་ཀྱི་ཚལ། མགོན་མེད་ཟས་སྦྱིན་གྱི་ཀུན་དགའ་ར་བ་ན་བཞགས་པའི་དུས་སུ། འཇིག་རྟེན་ན་གླེན་པ་གཏི་མུག་ཅན། མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ལས་རྣམས་ [4] བག་མེད་དུ་སྤྱོད་པ། སྲོག་གཅོད་པ། མ་བྱིན་པ་ལེན་པ། འདོད་པ་ལ་ལོག་པར་དབྱེན་པ། རྫུན་དུ་སྨྲ་བ། ཁྲ་མ་དང་། ཞེ་གཅོད་པའི་ཚིག་སྨྲ་བ། འདོད་ཆགས་དང་། ཞེ་སྡང་ཆེ་བ། ངན་པར་ལྟ་བ་ལེན་པ། མང་དུ་སྒོམ(གོམས)་པར་བྱས་པས། ཆུང་ངུ་ནི་དུད་འགྲོར་སྐྱེས། འབྲིང་དུ་བྱས་པ་ནི་ཡི་དྭགས་སུ་སྐྱེས། ཤས་ཆེར་བྱས་པ་ནི་སེམས་ཅན་དམྱལ་བའི་འཇིག་རྟེན་དུ་སྐྱེས་ཏེ། སྡུག་བསྔལ་རྣམ་པ་སྣ་ཚོགས་ཉོང(མྱོང)་སྟེ་སེམས་ཅན་དམྱལ་བའི་བསྲུང་མས་འཁྲིད་ནས། ལ་ལ་ནི་མཚོན་གྱི་དམྱལ་ཞིང་གཏུབ། ལ་ལ་ནི་མེའི་ཕན་ཚུན་གྲས་ཁམ་ཚད་བཅད། ལ་ལ་ནི་གཏུན་གྱི་ནང་དུ་བརྡུང་། ལ་ལ་ནི་རང་འཐག་ལ་འཐག ལ་ལ་ནི་རལ་གྲི་ལ་འཛེག །ལ་ལ་ནི་མེའི་ཤིང་རྟ་དང་། ཟངས་ཁོལ་མ་དང་ཆབ་དྲོན་མོ་དང་། འདམ་སྐྱུག་གི་ནང་དུ་བཀོལ་བ་སོགས་ཏེ། སྡུག་བསྔལ་ཤིན་ཏུ་མི་བཟོད་པ་རྣམ་པ་སྣ་ཚོགས་ཉོང་བར་འགྱུར་ཞིང་།

In the auspicious time during which the Buddha was staying in gNyan yod (Śrāvastī) in the forest of Prince Jeta in the mGon med zas sbyin gyi kun dga’ ra ba,3 [he taught that] in this world, because ignorant and stupid people have become used to indulging heedlessly in the ten non-virtuous actions, such as killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, telling lies, slander, speaking hurtful words, avarice, anger, adhering to wrong views, then at the very least they have been reborn as animals. For more serious actions, they have been reborn as hungry ghosts (preta) and for very severe actions, they have been reborn in an infernal world. Experiencing different types of suffering, the sentient beings were conducted by the guardians of hell. Some were pierced in the hell of weapons; some were bitten by fiery beings (me’i phan tshun gras kham tshad bcad);4 some were crushed with stone clubs; some were ground in a rotating mill; some encountered swords, some a chariot of fire; or they were boiled in a cauldron of boiling water or mud of vomit, and so on. They will experience a multitude of extreme and unbearable suffering.

ཚེ་འདིར་ཡང་། རིན་ཆེན་འཕྲེང་བ་ལས་སྲོག་བཅད་པས་ནི་ཚེ་ཐུང་འགྱུར།

རྣམ་པར་འཚེ་བས་གནོད་པ་མང་།

མ་བྱིན་ལེན་གྱི་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་འཕོང་།

བྱི་བོ་བྱས་པས་དགྲ་དང་བཅས།

རྫུན་དུ་སྨྲ་བས་བཀུར(སྐུར)་བ་མང་།

ཕྲ་མ་ཡིས་ནི་ཤེས་(བཤེས)་དང་བྲལ།

ཚིག་རྩུབ་ཡིས་ནི་མི་སྙན་ཐོས།

ངག་འཁྱལ་ཡིས་ནི་ངག་མི་བཙུན།

བརྣབ་སེམས་ཡིད་ལ་རེ་བ་འཇོམས།

གནོད་སེམས་འཇིག [5] པ་བྱིན་པར་བྱེད།

ལོག་པར་བལྟ་བ་ལྟ་ངན་ཉིད།

ཅེས། མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་རྣམ་སྨིན་བཟོད་གླག་(གླགས)་མེད་པ་གཟིགས་ནས། དེ་དག་གི་གཉེན་པོར་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་མདོ་གསུང་ཏེ། མི་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་སྤང་གི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

Furthermore, in this life, to quote from the Rin chen ’phreng ba,5

‘Killing will lead to a short life;

Causing harm leads to further harm;

Stealing results in complete loss of wealth;

Sexual misconduct creates enemies;

Telling lies leads to much denigration;

Slander leaves one without friends;

Those who use harsh words hear unpleasant things;

Those who gossip have ineffective speech;

With covetousness, one destroys hope;

A harmful attitude generates fear;

To see things wrongly [leads to] negative views.’

[The Buddha], having seen6 the unbearable consequences of the ten non-virtues, taught the sutrās on the ten virtues, as a countermeasure.

དཔལ་མགོན་འཕག་པ་ཀླུ་སྒྲུབ་ཀྱིས་ཀྱང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་གམས་(གདམས)་པ་རིན་ཆེན་འཕྲེང་བ། བློན་པོ་ལ་གདམས་པ་ཤེས་རབ་རྒྱལ་བ(བརྒྱ་པ)་མི་དམངས་ལ་གདམ་པ་སྐྱེ་བོ་གསོ་བའི་ཐིགས་པ་སྟེ། མི་དགེ་བཅུ་སྤང་བའི་བསྟན་བཅོས་གསུམ་མཛད།

The great protector, the noble protector, Nāgārjuna, wrote three śastras on rejecting the ten non-virtues: his advice to the king, called the Precious Garland (Rin chen ’phreng ba) (Ratnāvalī); the advice to ministers, called the Hundred Wise Sayings (Shes rab brgya pa) (Prajñāśataka); and the advice for ordinary people, called the Drop of Nourishment for the People (Skye bo gso ba’i thigs pa) (Jantuposanabindu).

དེ་དག་གི་རྗེས་སུ་འགྲེང་ནས་སྔོན་གྱི་ཆོས་རྒྱལ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་པའི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་འདི་ལྟར་སྣང་སྟེ།

Next, the history of the way in which previous dharma kings made their laws.

སྲོག་བཅད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on killing

ཤན་པ་དཀར་རུ་རྩེ་དང་། དམར་རུ་རྩེ་གཉིས་ཡོད་པས། ཁོང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ལུག་རེ་དང་། ཕག་པ་རེ་གསོད་པར་བྱས་པས། ཕག་པས་སྐད་ངན་བཏོན་པས། དམར་རུ་རྩེས་ལུག་གི་མིག་ལ་ས་བཏབ་ནས་བསད། ཕག་པའི་ལྕེ་བཅད་པས། དཀར་རུ་རྩེས་མ་ཕོད་སྟེ་བཏང་པས། ནགས་ཀྱི་ཁྲོད་དུ་བྲོས་ནས་ཕྱིན་པས། ཟ་རྒྱུ(རུ)མེད་པས་ལྟོགས་ནས་སྔོ་ཅིག་ཟོས་པས།དེའི་ནུས་པས་ནགས་ནས་རིང་ཁ་ཅིག་ཏུ་འཕུར་སོང་། དེ་རྔོན་པས་མཐོང་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་སྨྲས་པས། རྒྱལ་པོ་ན་རེ་འཁྲིད་ཤོག་གསུངས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་སྤྱན་སྔར་ཁྲིད་ཕྱིན་ནོ། རྒྱལ་པོ་ན་རེ་ཁྱོད་ལ་ཡོན་ཏན་ཅི་ཡོད་གསུངས། ཡོན་ཏན་ཅིག་ཀྱང་མ་མཆིས་ཏེ། ལྟོགས་ནས་སྔོ་ཅིག་ཟོས་ནས་བྱུང་བ་ཡིན་བྱས་པས།དེར་རྒྱལ་པོ་ངོ་མཚར་སྐྱེས་ནས། ཀ་རུ་རྩེ་ལ་བྱ་དགའ་ཆེན་པོ་བྱིན་ནོ།

There were two butchers, dKar ru rtse and the dMar ru rtse. Each had a sheep and a pig to be slaughtered. The pig let out an anguished cry. dMar ru rtse killed his sheep after throwing dust into its eyes and cutting the tongue of his pig. dKar ru rtse did not dare [to do the same] and let [his animals] go. He ran away into the middle of a wood. With nothing to eat, and growing hungry, he ate a plant. As a result of its power, he flew far away from the forest.

A hunter saw him and told the king. The king said, ‘Bring him to me’. When he had been led into the presence of the king, the king asked him, ‘What special qualities do you have?’ ‘I have no special qualities, I ate a plant when I was hungry and it just happened’. Then the king was struck with wonder and gave a great reward to dKar ru rtse.

དེའི་ཚེ་ལྷ་ཚངས་པས་སྨྲས་པ།

སྲོག་བཅོད་སྡིག་པ་བྱས་པས་ནི།

རྣམ་སྨིན་སྔོན་(མངོན་) དུ་གནང་བ་(སྣང་བ་) ནི།

དམར་རུ་རྩེ་ནི་དམྱལ་བར་ལྷུང་།

དཀར་རུ་རྩེ་ནི་མཐོ་རིས་ཐོབ།

དགེ་སྡིག་ལས་འབྲས་དེ་འདྲ་བ།

དངོས་སུ་སྣང་དེ་ཡ་ [6] མཚན་ཆེ།

ཞེས་སྲོག་གཅོད་སྤོང་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

In that regard, Brahma said,

‘In the case of sinful killing,

The karmic consequences are evident.

dMar ru rtse will fall into hell

And dKar ru rtse will reach a higher realm.

These are the consequences of virtue and sin.

This is a remarkable reality.’

In this way, the law on rejecting the taking of life was established.

མ་བྱིན་ལེན་བྱས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on stealing

རྐུན་མ་དགའ་བོ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། རྐུན་མ་མངས་པོ་དང་བཅས་ཁྱིམ་བདག་ཅིག་གི་མཛོད་རུ་རྐུ་རུ་ཕྱིན་པས། ཟླ་བོ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་ནོར་མང་པོ་འཁྱེར་སོང་བས། དགའ་བོ་བསམ་པ་སྐྱེས་ཏེ། ཁྲིམ་བདག་གི་(གིས)་དཀོན་མཆོག་ལ་དངོས་པོའི་ནོར་ལ། ང་ཇི་ལྟར་འཛིན་ཆགས་ཀྱི་རྐུ་བ་ར་སྙམ་ནས། གད་མོ་ཆེན་པོ་ཤོར་བ་དང་ཁྱིམ་བདག་གིས་ཚོར་བས་ཁོ་ལ་ཅི་ཡང་མ་བྱས།གཞན་དེད་པས། རྐུན་མ་དགའ་བོ་ལ་གཞན་ཚོས་ལེ་ལན་དེད་པའི་དུས་སུ། ཤིང་གི་ལྷ་མོ་འོད་འཆང་མས་ལུང་བསྟན་པས། ཁྱིམ་བདག་གིས་གསེར་གྱི་གཏེར་རྙེད་དེ་ཕྱུག་པོར་གྱུར། དེའི་ཚེ་ལྷ་དབང་པོ་བརྒྱ་བྱིན་གྱིས་སྨྲས་པ།

དགེ་བའི་བསོད་ནམས་མཐུ་ཡིས་ནི།

དགའ་བོ་ཁྱིམ་བདག་གསེར་དང་ལྡན།

རྐུན་མ་དགའ་བོ་མཐོ་རིགས་(རིས)་སྐྱེས།

ཟླ་བོ་གཞན་མ་ངན་སོང་ལྷུངས།

ཨེ་མ་ཤིན་ཏུ་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

མ་བྱིན་ལེན་སྤོང་སྦྱིན་པ་ཐོང་།

ཞེས་མ་བྱིན་ལེན་སྤངས་ནས་སྦྱིན་པ་གཏོང་བའི་ཁྲིམ་(ཁྲིམས)་བཅས་སོ།།

A thief known as dGa’ bo, along with a thief known as Mangs po, went to steal from the treasure chest of one householder. Their assistants had come to carry away many valuables. dGa’ bo thought, ‘I realize that I am stealing the householder’s precious jewels and material wealth out of avarice’, and he let out a great laugh. Having heard him, the householder did not do anything at all to him. He drove the others away. When the others blamed the theft on dGa’ bo, the tree goddess ’Od ‘chang ma, made a prophecy that the householder would discover a treasure of gold and become rich.

In that regard, Indra (lHa dbang po brgya byin) said,

‘By the power of virtuous merit,

dGa’ bo [is] the householder with gold,

The thief dGa’ bo was reborn into a superior realm,

The other assistant descended into the lower realms,

Aha! This is amazing.

Reject theft and give generously’.

In this way, by rejecting theft, the law of giving generously was established.

འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།།

The law on sexual misconduct

སྨད་འཚོང་མ་དགའ་བྱིན་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་དང་། གསལ་བའི་འོད་ཅེས་བྱ་བ་༢་ཡོད་པ་ལས། གསལ་བའི་འོད་ན་རེ། འདི་ལྟར་ངོ་ཚ་ཀྱུག་(སྐྱུག)་བྲོ། སྡིག་པ་ཆེ་ལ་ཚིམས་པ་མེད། འདི་འདྲ་བའི་ལས་བྱེད་པ་ཟེར་ནས། སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་དྲུང་དུ་ཕྱིན་ནས། ཚངས་སྤྱོད་ཀྱི་སྡོམ་པ་བླངས་ནས་བསྲུངས་པས། ལྷའི་བུ་མོ་རིན་ཆེན་འོད་ཅེས་བྱ་བར་སྐྱེས་སོ།སྨད་འཚོང་མ་དགའ་བྱིན་འདོད་པ་ལ་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཆེ་སྟེ། མཉམ་པོར་དགའ་བ་ལ་རིན་ཁོང་གི་སྟེར། འདི་ལས་ལྷག་པ་གང་ན་ཡོད་སྙམ་ནས། འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱད་པས། ཡི་དྭགས་ཀྱི་མངལ་འདམ་སྐྱུག་པའི་གནས་སུ་སྐྱེས་སོ།

དེའི་ཚེ་ལྷའི་བུ་རིན་ཆེན་བཟང་པོས་ཚིགས་སུ་བཅད་དེ་སྨྲས་པས།

འཁོར་བའི་འདོད་ཆགས་གསལ་འོད་ཀྱིས། [7]

སྤངས་པས་འོད་གསལ་ལྷ་རུ་སྐྱེས།

སྤྱད་པས་དགའ་སྦྱིན(བྱིན)་དམྱལ་བར་ལྷུང།

འདི་ཡང་ཡ་མཚན་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

འདོད་ལོག་སྤོང་ལ་ཚངས་སྤྱོད་བསྲུངས།

ཞེས། འདོད་ལོག་སྤངས་ནས་ཚངས་སྤྱོད་སྡོམ་པ་བསྲུང་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

There were two prostitutes, known as dGa’ byin and gSal ba’i ʼod. gSal ba’i ʼod said, ‘By acting like this I experience great shame. I am not satisfied with this great sin, which will have (karmic) consequences’. Having gone to the Buddha, and taken vows of pure conduct and kept them, she was born as a the daughter of a god, known as Rin chen ʼod.

The prostitute dGa’ byin had great (sexual) desire. Equally, she was happy with a man's gift of money. She thought, ‘What is better than this?’ and she committed sexual misconduct. She was reborn in the swamp of vomit that is the womb of a hungry ghost.

Regarding that, lHa’i bu Rin chen bzang po spoke these verses:

‘By rejecting worldly (sexual) desire,

gSal ʼod was born as a luminous deity (’od gsal).

By practising (sexual desire), dGa’ byin descended into hell.

This is very amazing.

To reject sexual misconduct, pure conduct should be practised’.

In this way, by rejecting sexual misconduct, the law on observing pure conduct was established.

རྫུན་སྨྲས་བའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on lying

རྒྱ་གར་ལ་སྡང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་འཆར་བྱེད་ཅེས་བྱ་བ་ལ། ཁོལ་པོ་བྲམ་ཟེ་རྫུན་མེད་ཅེས་པ་དང་། རིགས་ངན་རྫུན་པོ་ཆེ་བྱ་བ་གཉིས་ཡོད་པ་ལས། དེ་གཉིས་ལ་མ་ཧེ་སྟོང་གི་ཁྱུ་མཆོག་སྟག་རིས་བྱ་བ། རྩྭ་ཡི་ཕུད་ཟ། ཆུ་ཡི་ཕུད་འཐུང་། འགྲོ་ན་ལམ་འདྲེན། ལྡོག་ན་མཇུག་སྡུད་པ་ལ་ཁ་མཐོན་པོར་བསྡད་ནས།གཅན་གཟན་གྱི་བྱ་ར་བྱེད་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པས། རྫི་བོ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་དེ་བསད་ནས་བཟོས་པས། དེར་རིགས་ངན་ན་རེ། བྲམ་ཟེ་ལ། འུ་ཅག་གཉིས་ལ་རྒྱལ་པོས་ཆད་པ་ཡོང་བས། ཁྱུ་མཆོག་སྟག་རིས་གཡང་ལ་ལྷུང་ནས་ཤི་བྱས་པ་གྲག་ཟེར། བྲམ་ཟེ་ན་རེ། ངས་སྐྱེས་ནས་རྫུན་བྱེད་མ་ཉོང(མྱོང)་བས། ད་རེས་ཡང་མི་ཤེས་ལས་ཆེ་བྱས་པས།རྫུན་མ་ཤེས་ན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཆད་པས་གསོད་དུ་འོང་བས་ཅིས་ཀྱང་སྨྲོས་ཤིག་ཟེར་ནས། རྫུན་བྱ་བར་ཆད་དོ། དེར་བྲམ་ཟེས་རྫུན་ཤེས་སམ་མི་ཤེས་ལྟས་པས། མི་ཤེས་པར་འདུག་ནས། དྲང་སྲོང་སྨྲ་མཉམ་ཡོད་ཙ་ན། དེར་རྒྱལ་པོ་དང་འཕྲད་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་ན་རེ། མ་ཧེ་སྟོང་ཁྱུ་ཚང་ངམ། ཁྱུ་མཆོག་སྟག་རིས་འཚོ་འམ་བྱས་པས།བྲམ་ཟེས་རྫུན་མ་ཤེས་ནས། ཁྱུ་མཆོག་སྟག་རིས་ངེད་ཀྱིས་བསད་བྱས་པས། འ་ཡི་ཟེར་ནས། བྲམ་ཟེ་ལ་བྱ་དགའ་ཆེན་པོ་བྱིན། རིགས་ངན་གྱི་ལྕེ་བཅད་དོ།

In India, there was a fierce king, known as ‘Char byed,7 who had two servants: a Brahmin called rDzun med and a low-class man named rDzun po che. The two of them had [care of], a buffalo who was the leader of a thousand-strong herd, called Khyu mchog sTag ris, who ate the best grass and drank the freshest water, and when he went he led the way, and when he returned he brought up the rear. When sitting on a high ridge, he kept watch for wild animals. The two herders killed and ate [the buffalo]. Then the low-class [servant] said to the Brahmin, ‘The king is going to punish the two of us. Let us tell him that Khyu mchog stag ris fell off a cliff and died’. The Brahmin said, ‘Since I was born, I have never lied, and I probably do not know how to, even now, and if I cannot lie, the king will punish us with death. But in any event, something must be said.’ He decided that he would lie [but], having tried to see if he could lie or not, and realising that he could not, the Brahmin spoke truthfully, like a sage (drang song). When they met the king, the king said, ‘Is the herd of a thousand buffaloes complete? Have you looked after Khyu mchog stag ris?’ Since the Brahmin could not lie, he said, ‘We killed Khyu mchog stag ris, alas’. The Brahmin was given a great reward and the low-class [servant] had his tongue cut.

དེའི་ཚེ་ལྷ་དབང་ཕྱུག་ཆེན་པོས་སྨྲས་པ།

རྫུན་ལས་ཟློག་ནས་བདེན་པར་སྨྲས།

བྲམ་ཟེ་དེས་ནི་བྱ་དགའ་ཐོབ།

རིགས་ངན་ལྕེ་བཅད་ངན་སོང་ལྷུང་།

ཨེ་མ་ངོ་མཚར་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཆེ།

ཞེས། རྫུན་སྤངས་བདེན་པར་སྨྲ་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ། [8]

Regarding that, Shiva (Lha dbang phyug chen po) said:

By refusing to lie and speaking the truth,

The brahmin received a reward,

The low-class [servant] had his tongue cut and fell into lower realms,

The amazing thing is utterly true,

In this way, the law for rejecting falsehood and speaking the truth was established.

ཚིག་རྩུབ་སྨྲ་བའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on harsh speech

རྒྱལ་པོ་ས་རྒྱལ་གྱི་འཁོར་ན། ཁྱིམ་བདག་ནག་པོ་བརྩེགས་པ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། དུས་རྟག་ཏུ་ཚིག་རྩུབ་མོ་སྨྲ་བ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལས། བྲམ་ཟེ་པདྨའི་ངང་ཚུལ་བྱ་བ། ཐམས་ཅད་ལ་ངག་འཇམ་དང་ཞི་དུལ་དུ་སྨྲ་བ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་དེས། ནག་པོ་བརྩེགས་པ་ལ་དེ་སྐད་མ་ཟེར། མཚོན་གྱི་རྨ་ནི་འཚོ་བ་ཡིན། ཚིག་གི་རྨ་ནི་འཚོར་བ་མི་བཏབ།བྱ་བ་ཡིན་བྱས་པས། ཁོ་ན་རེ། ཚིག་རྩུབ་ནི་ཁས་དྲག་གི་དཔའ་རྟགས་ཡིན། ཀུ་ཐོ(ཅོ)་ཅན་གྱི་ཁས་མནོན་ཡིན་པས། ང་ལ་སུས་ཟློག་མི་ནུས་པ་ཡིན་ཟེར་ནས། ཚིག་རྩུབ་མོ་དང་ཁ་ཞེའི་ཚིག་སྨྲ་བས། ཡུལ་མི་ཐམས་ཅད་གྲོས་བྱས་ནས། ནག་པོ་བརྩེགས་ཀྱི་ནོར་ཐམས་ཅད་ཕྲོགས་ནས་བྲམ་ཟེ་པད་མའི་ངང་ཚུལ་ལ་བྱིན་པས།

In the retinue of King Sa rgyal8 there was one householder called Nag po brtsegs pa, who always spoke harshly. There was [also] a brahmin, called Padma’i ngang tshul, who spoke gently and calmly to everyone. He said to Nag po brtsegs pa: ‘Do not talk like that; it is said that a knife wound can be survived, but a verbal wound cannot’. [Nag po brtsegs pa] said: ‘Harsh speech is the talk of a hero and silences frivolous chatterers; no one can contradict me’. Because his speech was harsh and hurtful, all the people of the area consulted among themselves. They seized all of Nag po brtsegs pa’s wealth and gave it to the brahmin Padma’i ngang tshul.

དེའི་ཚེ་དྲི་ཟའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡུལ་འཁོར་སྐྱོང་གིས་སྨྲས་པ།

ཚིག་རྩུབ་ཞེར་འདེབས་སྨྲས་པ་ཡིས།

ཁྱིམ་བདག་ཆེན་པོ་ནོར་དང་བྲལ།

ངག་འཇམ་ཀུན་གྱི་ཡིད་དང་མཐུན།

བྲམ་ཟེས་ནོར་ཐོབ་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

ཞེས་ཚིག་རྩུབ་སྤངས་ལ། ངག་འཇམ་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

In this regard, Dri za’i rgyal po Yul ’khor skyong (King of Gandharvas) said:

Because of his harsh and hurtful speech,

A great householder was separated from his wealth.

Gentle speech is harmonious with everyone’s feelings.

It is wonderful that the Brahmin gained the wealth.

In this way, to eliminate harsh speech, the law on speaking gently was established.

ངག་འཁྱལ་སྨྲ་བའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on gossip

གྲོང་ཁྱེར་སེར་སྐྱ་ན། མགར་བ་མུ་ཅོར་སྨྲ་བ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། ངག་འཁྱལ་ཅི་མིན་སྨྲ་བ་ཡོད་སྐད་པ་ལ། འབའ་རོ་གྲགས་པ་སང(སེང)་གེ་བ་བྱ་བ་དོན་དང་འབྲེལ་བའི་གཏམ་སྨྲ་བ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པས། མགར་ཚང་དུ་དགེ་སློང་ཉི་མ་འོད་ཅེས་བྱ་བས་བཟོ་འཆོས་པ་ལྟར་ཕྱིན་པས། མགར་བས་ངག་འཁྱལ་ཅི་མིན་སྨྲ་བས། འབའ་རོ་ན་རེ།མགར་བ་འདི་དོན་མེད་པའི་བབ་ཅོལ་དེ་ཙམ་མ་སྨྲ། དགེ་སློང་ཁམས་ཟློག གྲང(བྲང)་ཁང་དུ་གཤེགས་འཚལ་བྱས་པས། དགེ་སློང་ངག་འཁྱལ་ཉན་ཉན་ནས། ཆོས་དོན་ཡོལ(ཡེ)་ནས་མ་ཐོས་པས། ཁམས་འཁྲུགས་ནས་འགྱེལ་བས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཞལ་ནས་ངའི་མཆོད་གནས་འདིས་ཅི་ཉེས་བྱས་པས། འབའ་རོས་གོང་གི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་སྙད(བསྙད)་པས།དེར་རྒྱལ་པོས་འབའ་རོ་གྲགས་པ་སེང་གེ་ལ་བྱ་དགའ་བྱིན། མགར་བ་མུ་ཅོར་ [9] སྨྲ་བའི་ལྕེ་བཅས་པས།

In the town of Kapila, it is said, there was a blacksmith called Mu cor who was unrivalled as a gossip. Another, called ’Ba’ ro grags pa seng ge, spoke meaningfully. A monk, called Nyima ’od, went to the blacksmith’s shop to see about having some work done. The blacksmith engaged in excessively idle chatter. ’Ba’ ro said, ‘Do not speak like this blacksmith, with his nonsense and mindless prattle. It is unhealthy for a monk. You should go to your residence’. Having listened at length to the idle chatter, and since he was not listening to any religious matters, the monk became upset and collapsed. The king asked what had harmed his monk. ’Ba’ ro related the above story. Then the king gave ’Ba’ ro grags pa seng ge a reward and had the chattering tongue of the blacksmith Mu cor cut.

དེའི་ཚེ་ལྷའི་བུ་དྲང་སྲོང་སྐར་མདའ་གདོང་གིས་ཚིགས་སུ་བཅད་དེ་སྨྲས་པ། ངག་འཁྱལ་བ་ནི་སྨྱོན་པ་འདྲ། མུ་ཅོར་སྨྲ་བ་ལྕེ་དང་བྲལ། འབའ་རོ་ཡིས་ན་བྱ་དགའ་ཐོབ། ཨེ་མ་ངོ་མཚར་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཆེ། ཞེས་ངག་འཁྱལ་སྤངས་ལ་དོན་དང་ལྡན་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

In this regard, Lha’i bu drang srong9 skar mda’ mdong10 said these words:

Those who engage in idle chatter are like mad men.

Mu cor lost his tongue.

’Ba’ ro was given a reward

This is amazing.

In this way, to eliminate gossip, the law for engaging in meaningful speech was established.

ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་བྱས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on slander

ཡུལ་མ་ག་དྷའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་གཟུགས་ཅན་སྙིང་པོ་དང་། འབའ་རོ་ཡུལ་དཔོན་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། འབྱོར་པ་དང་ལྡན་པ་ཤིན་ཏུ་མཛའ་བ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལས། དེའི་བར་དུ་ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་མཁན་དྲི་མེད་ཅེས་བྱ་བས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་དྲུང་དུ་ཕྱིན་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་ལས་ང་བཟང་། ནོར་ཡང་ང་མང་འཁོར་ཡང་ང་མང་། འཁོར་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ལྟོས་ན་ང་དྲག་གོ་ཞེས་བྱ་བའི་ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་སྐྱལ(བསྐྱལ)་ལོ།འབའ་རོའི་དྲུང་དུ་ཕྱིན་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་ན་རེ། འབའ་རོའི་ཡུལ་གྱི་དཔོན་པོ་ང་ཡིན། ངའི་ཁོལ་པོ་ཡིན་ཏེ། ངས་སྨྲ་བ་ལ་མི་ཉན་ན་སྲོག་དང་འབྲེལ(བྲལ)། ནོར་འཕྲོག་ཟེར་བའི་ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་སྐྱལ(བསྐྱལ)་ལོ། འབའ་རོ་དང་རྒྱལ་པོ་གཉིས་འཁྲུག་པ་བྱེད་པར་ཐུག་པ་ལ། བྲམ་ཟེ་ཛམྦྷ་ལ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ཐམས་ཅད་སྡུམ་པ་ལ་མཁས་པས་སྡུམ་བྱས་ཏེ།རྒྱལ་པོས་ཡུལ་བདེ་བ་ལ་བཀོད། དེ་ནས་རྒྱལ་པོ་དང་འབའ་རོ་གཉིས་སོ་སོར་ལོ་རྒྱུས་བྱས་པས། ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་མཁན་གྱི་ཕྲ་མ་ཡིན་པ་རིག་ནས། ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་མཁན་གྱི་ལྕེ་བཅད། བྲམ་ཟེ་ཛམ་ལས་སྡུམ་བྱས་པའི་རྔན་པར། གཉིས་ཀར་གྱིས་གསེར་སྲང་བརྒྱ་བརྒྱ་བྱིན་ནོ།

The king of Ma ga dha, gZugs can snying po,11 and [a man] known as the governor (yul dpon) of ʼBa’ ro, were wealthy and extremely good friends. Between them came a troublemaker known as Dri med. He went to the king and said, divisively, ‘[’Ba’ ro says that] 'I am superior to the king: I have more wealth and a larger retinue. Compared to the royal retinue, mine is superior’. Then he went to ’Ba’ ro and said, divisively, ‘The king says that I am the governor of ’Ba’ ro; [you are] my servant; if you do not obey my orders I will put you to death and seize your wealth’. ’Ba’ ro and the king were on the point of starting a war. Then the brahmin Dzambhala (Jambala),who was skilled in mediating all cases, conciliated between them. The king brought peace to his land. Then the king and ’Ba’ ro each related his story. Having realised the divisive nature of the troublemaker’s words, they had his tongue cut. In order to reward the brahmin Dzamla, who had reconciled them, each gave him one hundred gold srang.

དེའི་ཚེ་མིའམ་ཅིའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལྗོན་པས་སྨྲས་པ།

ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མས་གཞན་འབྱེད་རྣམ་སྨིན་ནི།

ལྕེ་བཅད་ངན་སོང་གནས་སུ་ལྷུང་།

བྲམ་ཟེ་ཛམ་ལའི་སྡུམ་ཀྱི(གྱིས)་ནི།

གསེར་སྲང་ཉིས་བརྒྱའི་བྱ་དགའ་ཐོབ།

རྣམ་སྨིན་འཕྲལ་འབྱུང་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

ཞེས་ཁྲ(ཕྲ)་མ་སྤངས་ལ་མི་མཛའ་སྡུམ་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

In this respect, Mi’am ci’i rgyal po Ljon pa (the Kinnara king) said:

The result of dividing others through slander,

Is that your tongue will be cut and you will fall into a lower realm.

The brahmin Dzamla, who mediated

Received a reward of two hundred gold srang.

This immediate result is wonderful.

In this way, to eliminate slander, the law on friendly and conciliatory speech was established.

བརྣབ་སེམས་བྱས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on covetousness

ལྷོ་ཕྱོགས་སི་ཏའི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ན། ཁྱིམ་བདག་འོད་གསལ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། ནོར་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཕྱུག་པ། རང་གི་ནོར་ལ་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཆགས་པ། གཞན་གྱི་ནོར་ལ་ཁེ་དང་རྒྱུ་འོག་གི་འབྲེལ་པ(བ)། ཡིད་ཀྱིས་འཕྲོག་པ། [10] བརྣམ་སེམས་དང་བཅས་པ། ལྷག་པར་ཡང་དཀོན་མཆོག་གི་ནོར་ལ་བརྣབ་སེམས་དང་བཅས་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལ། ཡང་ལི་ཙ་བྱི་དྲི་མ་མེད་པར་གྲགས་པ།ནོར་གྱི་ཆགས་པ་དང་བྲལ་བ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པས། ཁྱིམ་བདག་འོད་གསལ་ལ་སྨྲས་པ། ཁྱོད་ལ་ཅི་ཙམ་པའི་ནོར་ཡོད་བཞིན་དུ། གཞན་གྱི་ནོར་ལ་ཆགས་སེམས་ཀྱི་བརྣབ་སེམས་བྱེད་དམ་དེ་མ(མི)་ལེགས། ལྷག་པར་དཀོན་མཆོག་གི་ནོར་ལ་བརྣབ་སེམས་དང་། འཇིག་རྟེན་འདིར་ཡང་བཀྲ་མི་ཤིས། ཕྱི་མ་ཡང་ངན་སོང་དུ་འགྲོ་བ་ན་ནོར་གྱི་ཞེན་པ་བྱ་བ་མི་དབུལ་པོ་ལ་ཡོང་བ་ཡིན་པ་དང་།ཕྱུག་པོ་ལ་ནོར་དེ་ཙམ་པས་ཆོག་མོད་བྱས་པས། ལན་དུ་དེ་ལས་ཀྱང་མི་ལྟོགས་ལ་ནོར་གྱི་ཟླ་མེད་པས་ཅི་བྱེད། ཕྱུག་པོ་ལ་ནོར་གྱི་ཟླ་བོ་ཡོད་པས་སླར་ཀྱི་རྐྱེན་ནོར་ལ་དགོས་པ་ཡིན། ནོར་ལ་ཆོག་ཅི་ཡོད། དཀོན་མཆོག་གི་ནོར་ལ་མི་རུང་བ་ཅི་ཡང་མི་ཡོང་། དེ་སྐད་ཟེར་ཞིང་ཞེ་འདོད་བརྣབ་སེམས་བྱེད་པ་ཞིག་ཡོད་པ་ལས།དེར་གློ་བུར་དུ་འོད་གསལ་གྱི་ནོར་ཐམས་ཅད་མིས་ཕྲོགས། ཁོ་རང་གི་སྙིང་གནོད་སྦྱིན་བི་ན་ཡ་ཀས་དངོས་སུ་བཏོན་ནས་ཤི་སྐད། ཚེ་ཕྱི་མ་ཡང་ཡི་དྭགས་སུ་སྐྱེས་སྐད་དོ། ལི་ཙ་བྱི་ལ་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ཀྱི་མིས་བསྙེན་བཀུར་མང་དུ་བྱས་ནས། ནོར་ཟས་སོགས་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་མང་དུ་བྱུང་ངོ་།

In the southern kingdom of Si ta, there was a householder called ’Od gsal. He was extremely rich and loved his wealth excessively. He was infatuated with the idea of obtaining profit and property from other people’s wealth. Being exceptionally avaricious, he even coveted the wealth of the Three Jewels. There was a nobleman, Li tsa byi, who was known for his purity and who had no desire for wealth. He said to the householder ’Od gsal, ‘You are already so wealthy, does your avarice make you covet the wealth of other people? That is not good. To covet the most precious treasure brings misfortune in this world. Later, when people go to the lower realms, those who are attached to wealth will become poor people. So being wealthy is adequate, indeed.’In response, being a truly avaricious person, [’Od gsal] said: ‘For a hungry person, since he has no wealthy companions, what can he do? Since a rich person has wealthy companions, he needs sources of wealth repeatedly. What is sufficient wealth?As for the wealth of the Three Jewels, it is not at all inappropriate’. Suddenly, people seized all of ʼOd gsal’s wealth. It is said that the demon (yakṣa) Bi na ya ka actually plucked out his heart, and he died. In the next life, it is said, he was born as a hungry ghost. The people of that kingdom had great respect for Li tsa byi and he received a great deal of material wealth‘.

སའི་ལྷ་མོ་བསྟན་མས་སྨྲས་པ།

ཆོག་ཤེས་མེད་པའི་ནོར་འདོད་ནི།

འདིར་སྡུག་ཕྱི་མ་ངན་སོང་ལྷུང་།

ཆགས་ཞེན་མེད་པའི་ལི་ཙ་བྱི།

བདེ་ལ་ཕྱུག་པ་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

ཞེས་པ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས། བརྣབ་སེམས་སྤངས་ནས་ཆགས་པ་སྐྱུང་བའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

Sa’i lha mo bstan ma said:

Those who have an insatiable desire for wealth

Suffer now and later fall into the lower realms.

Li tsa byi, who was without desire,

Was rich in happiness. How very wonderful.

On this basis, by eliminate avarice, the law on reducing attachment was established.

གནོད་སེམས་བྱེད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on malevolence

སིངྒ་ལའི་རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ན། གྱད་ཟླ་བ་བཟང་པོ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། ཐམས་ཅད་བརྡུང་ཅིང་འཐེན་འཕྲོག་བྱེད་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་གསེར་གཟུང་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། བྱང་ཆུབ་ཀྱི་སེམས་དང་ལྡན་པ། ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱི་སྐྱབས་བྱེད་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལ། ཟླ་བ་བཟང་པོ་ནི་ཀུན་གྱི་མཐོང་སར་གཤིན་རྗེ་ཆོས་རྒྱལ་གྱིས་མངོན་གསུམ(སུམ)་དུ་འཁྲིད་ནས་དམྱལ་བར་སྐྱེས་སྐད།རྒྱལ་པོ་གསེར་ [11] གཟུང་ནི་མངོན་སུམ་དུ་ལྷ་རུ་སྤྱན་དྲངས་སོ་སྐད།

In the kingdom of Singa la, a strong man, Zla ba bzang po, was beating and robbing everyone. The king, gSer gzung, had an enlightened mind and protected everyone. In the sight of everyone, Zla ba bzang po was led away by the Lord of Death, and reborn in a hell realm, so it is said. The king, gSer gzung, was invited to [the realm of] the gods, so it is said.

དེ་ལ་རྣམ་ཐོས་སྲས་ཀྱིས་སྨྲས་པ།

ཀུན་ལ་གནོད་ཅིང་གནོད་སེམས་ལྡན་པ་ཡིས།

གྱད་ནི་མངོན་སུམ་གཤིན་རྗེས་ཁྲིད།

བྱང་སེམས་ལྡན་པའི་གསེར་གཟུང་ནི།

ལྷ་ཡི་གནས་དྲངས་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

ཞེས་པ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས། གནོད་སེམས་སྤངས་ལ་བྱང་སེམས་དང་ལྡན་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

In that regard, rNam thos sras12 said:

The strong man with a malevolent mind, who harmed everyone,

Was actually led away by the Lord of Death.

gSer gzung, with the enlightened mind,

Was invited to the realm of the gods. How amazing.

On that basis, to eliminate malevolence, the law on having an enlightened mind was established.

ལོག་རྟ(ལྟ)་བྱས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ནི།

The law on wrong views

མུ་སྟེགས་ཀྱི་སྟོན་པ་འོད་སྲུང་རྫོགས་བྱེད། ཅེས་བྱ་བ་ན་རེ། རྟག་ཆད་གཉིས་ལ་འཆད་པ་སྡིག་པ་ཆེ། ཚེ་སྔ་ཕྱི་མེད་པས་དགེ་སྡིག་མེད། ལས་ལ་རྒྱུ་འབྲས་མེད་ཅིང་དཀོན་མཆོག་གསུམ་རྫུན་ཡིན་ཟེར་ནས། རང་ཡང་དེ་ལྟར་བྱེད་ཅིང་། གཞན་ལ་ཡང་དེ་ལྟར་སྟོན་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལ། དགེ་སློང་སེང་གེ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ།ཚེ་སྔ་ཕྱིའི་རྒྱུ་འབྲས་ལ་ཡིད་ཆེས་ནས། དཀོན་ཅོག་གསུམ་ལ་དད་པ་དང་གུས་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལས། གོང་གི་རྣམ་སྨིན་གྱིས་འོད་སྲུང་རྫོགས་བྱེད་ནི་མནར་མེད་པའི་སེམས་ཅན་དམྱལ་བར་སྐྱེས། དགེ་སློང་སེང་གེ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ནི། ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་བདེ་བ་ཅན་གྱི་ཞིང་ཁམས་སུ་སྐྱེས་སོ།

’Od srung rdzogs byed, a heretical teacher, said this: ‘To explain eternalism and nihilism is a great sin. Without past and future lives, there is no virtue and vice. There is no karmic cause and effect and it is wrong to speak of the Three Jewels’. He acted like that himself and taught it to others. A monk, known as Seng ge, believed in the cause and effect of past and future lives, and had respect and devotion to the Three Jewels. The result of this was that ’Od srung rdzogs byed was reborn asa hell being in the mnar med infernal realms, while the monk Seng ge was reborn in the blissful western realm.13

བྱང་ཆུབ་སེམས་དཔའ་རྡོ་རྗེ་སྙིང་པོས། ཚིགས་སུ་བཅད་དེ་འདི་སྐད་ཅེས་སྨྲས་སོ།

རྫུ་འཕྲུལ་ལྡན་པའི་འོད་སྲུངས་ནི།

མངོན་གསུམ་མནར་མེད་གནས་སུ་ལྷུང་།

ལོག་པར་ལྟ་བ་སྙིང་རེ་རྗེ།

སེང་གེ་ཡང་དག་དོན་དང་ལྡན།

ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་བདེ་བ་ཅན་དུ་སྐྱེས།

ཡ་མཚན་ཆེ་ལ་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ།

ཞེས་པ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་ལོག་ལྟ་སྤངས་ལ་ཡང་དག་པར་བལྟ་བ་ལྡན་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ།

The bodhisattva Rdo rje snying po said this verse:

’Od srungs, with the magical powers,

Actually descended into one of the infernal realms.

His wrong views are pitiable.

Seng ge, with his correct views,

Was reborn in the blissful Western realm.

This is amazing.

On this basis, to eliminate wrong views, the law on holding correct views was established.

དེས་ན་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་གཉིས་མིང་འདོགས་དང་སྤོང་བྱེད་སྒོ་ནས་འགལ་ཀྱང་། སྤང་བྱའི་སྒོ་ནས་མི་འགལ་བས་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་རྣམ་དག་ཅིག་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་ཁོ་ནར་འདུག་གོ། ༒

Even though the religious and royal laws are contrary (different) in terms of their names and methods of abandoning [non-virtue], because they are not contrary in terms of what ought to be abandoned, the proper royal laws are just like the religious laws.

གཉིས་པ་

Second

རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་མ་བཅས་ཀྱི་ཕན་ཡོན་དང་ཉེས་དམིགས་བཤད་པ་ནི།

An explanation of the good and bad effects (phan yon dang nyes dmigs) of applying or not applying royal law

ཡིད་འཕྲོག་མའི་གཏམ་རྒྱུད་ལས། བྱང་ཕྱོགས་ལྔ་ལྡན་སྐྱིད་ཅིང་རྒྱག་པ་དེ་རྒྱལ་པོས་རྒྱལ་སྲིད་ཆོས་བཞིན་སྤྱད་པ་དང་། འབངས་འཁོར་གཡོག་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་ [12] རྒྱལ་པོའི་བཀའ་ལ་ཉན་པས་ཡིན། ལྷོ་ཕྱོགས་ལྔ་ལྡན་སྡུག་ཅིང་འཕོངས་པ་དེ། རྒྱལ་པོས་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ཆོས་བཞིན་མ་སྤྱད་པ་དང་། འབངས་འཁོར་ཡོག་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་རྒྱལ་པོའི་བཀའ་ལ་མ་ཉན་པས།སྡུག་ཅིང་འཕོངས་པ་ཡིན་ཞེས་པ་དང་།

In the Yig ’phrog ma’i gtam rgyud,14 it is said:

In the north, at the time of the skyid cing rgyag pa, one of the five-fold areas [characterized by happiness], the king enacted his government in accordance with the dharma (chos bzhin), and the people and servants obeyed his orders. In the south, at the time of the sdug cing ʼphongs pa, another of the five-fold areas [characterized by unhappiness], the king did not enact the laws in accordance with the dharma, the people and servants did not obey his orders, and there was unhappiness and misfortune.

བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་ཀྱི་མདོ་ལས་ཀྱང་། ཉེས་ལ་ཉེས་པ་མ་བཅད་ན། དེའི་ཉེས་པ་ཡུལ་གྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་སྨིན་པར་འགྱུར་ཞེས་པ་དང་། མཁས་པ་གཞན་གྱི་ཇུས་ལ་གནོད་པའི་མི་དེ་ལ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་བརྡ་འདེད་མ་བྱས་ན། ཕྱིས་ངན་བྱེད་སྙིང་ཁམས་བསྐྱེད་ཅེས་བྱ་བ་གསུངས་གདའ་བས།

In a sutra of the Buddha, it is said:

If a bad person is not stopped, he will become the king of the land.

And, as for the actions of wise people towards others, if a person’s harm is not subject to a legal process (khrims kyi brda ʼded), later an evil-doing disposition will develop.

ཁྲིམས་བདག་དང་བར་མི་བྱེད་པ་དག་གིས། དབྱེ་བ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་མཉམ་ཉིད་ཁོང་ཡོན་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ། གཡོ་སྒྱུ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་ཞལ་ཆེ་སྣག་བུམ་མ། ཉེས་པ་སྤང་ཞིང་དྲང་པོ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་ཞལ་ཆེ་ཡིད་ཀྱི་རི་མོ། འགྲིག་པ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་མཛངས་པ་འཕྲུལ་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེའི་སྒོ་ནས་ཁྲིམས་དང་ཁ་མཆུ་བཅད་པས་བསོད་ནམས་ཆེན་པོ་ཐོབ།

Judges and mediators and their activities:

The principle (gtso bor ʼdon pa) of distinguishing (dbye ba), is the rule (zhal lce) concerning impartiality and gifts;

The principle of deceit (g.yo sgu), is the rule of the ink-pots;

The principle of truth and rejecting what is wrong is the rule which creates a mental picture;

The principle of suitability is the rule of wisdom;

If they act according to these principles, decided cases and arguments (khrims dang kha mchu) will be very meritorious.

སྔོན་གྱི་སྣ་བོ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། ཕུ་རུ་བསམ་གཏན་སྒོམ་པ་དང་། མདའ་རུ་མི་མཛའ་སྡུམ་པ་གཉིས་ཁྱད་མེད་དུ་གསུང་གདའ།

Former leaders (those who set examples) have said that to practise meditation in the upper parts and to reconcile enemies in the lower parts, these are no different.

ཡབ་ལྷ་དྲི་བཟང་ན་རེ། དྲང་པོ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་ཞལ་ལྕེ་ཡིད་ཀྱི་རི་མོ། འགྲིག་པ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་མཛངས་པ་འཕྲུལ་གྱི་ཞལ་བཅེ(ལྕེ)། འབྱེད་པ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་མཉམ་ཉིད་ཁོང་ཡོན་གྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། གཡོ་སྒྱུ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་ཞལ་ཆེ་སྣག་བུམ་མ། འདི་བཞིར་ཐམས་ཅད་འདུས་ཟེར་རོ།།

According to Yab lha dri bzang15 it is said that:

The main principle of truth, being the rule which creates a mental picture,

The main principle of suitability, being the rule of manifesting wisdom,

The main principle of distinguishing, being the rule concerning impartiality and gifts,

The main principle of deceit, being the rule of the ink-pot.

This summarizes the four.

༈ གསུམ་པ།

Third

བོད་དུ་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ནམ་གྱི་དུས་སུ་བྱུང་བཤད་པ་ནི།

An explanation of the time at which the royal law appeared in Tibet

སྔོན་གྱིས་དུས་ན་བོད་ཡུལ་མུན་པའི་རྨག(སྨག)་རུམ་དང་འདྲ་བ་འདིར། རྒྱལ་ཕྲན་བཅུ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་སོ། ཁང་པ་ཐམས་ཅད་རི་ཁྱིམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས། ལས་སུ་རྔོན་པ་བྱེད། ཟས་སུ་ཤ་ཟ་ཁྲག་འཐུང་། གོས་སུ་ལྤག་པ་གྱོན། དགེ་སྡིག་ངོ་མི་ཤེས་པ་ལ། སྤྲུལ་པའི་ཆོས་རྒྱལ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ་དེ་ཉིད་ཀྱིས་བོད་འབངས་བདེ་ལ་བཀོད་པའི་ཕྱིར།ཆོས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལ་བརྟེན་པའི་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་བཅའ་བ། འདོད་ཡོན་ལྔ་སྤེལ་བ། ཕན་ཚུན་དུ་ [13] སྐྱེས་བསྐུར་བ།

In an earlier time, Tibet was a land of darkness and obscurity and the twelve petty kingdoms [each] had law. All the houses were like mountain huts, the work was hunting, for food people ate meat and drank blood, they wore skins, and they were unable to distinguish good from bad. So, in order to establish the happiness of the Tibetan subjects, the emanation religious king, Srong btsan sgam po, drew up royal laws on the basis of the ten virtues of the religion (chos); he increased the five desirable qualities and bestowed blessings on all.

མངའ་འོག་གི་འབངས་རྣམས་ལ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་བཀའ་བསྒོ་བ་ལ། བོད་ན་ཡི་གེ་མེད་པས། བློན་པོ་དབང་པོ་རྣོ་བ་བདུན་རྒྱ་གར་ལ་ཡི་གེ་སློབ་ཏུ་བཏང་བས། མཐའ་འདྲེ་རྣམས་དང་ཐུག་ནས་ལོག་པས། དེ་ནས་ཐུན་མི(ཐོན་མི)་ཨ་ནུའི་བུ། ཐོན་མི་སམྦྷོ་ཊ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ། དབང་པོ་རྣོ་བ། ཡིད་ཞུང(གཞུངས)་བ། ཡོན་ཏན་དུ་མ་དང་ལྡན་པ་ཅིག་ཡོད་པ་ལས།སྐུ་ནོར་རྫས་གསུམ་ལ་མ་གཟིགས་པར་གསེར་མང་པོ་སྐུར་ནས་རྒྱ་གར་ལ་ཡི་གེ་སློབ་ཏུ་བཏང་ངོ་།

In order to instruct the subjects under his power in the true doctrine, and because there was no writing in Tibet, he sent seven clever ministers to India to learn how to write. However, meeting demons at the border, they turned back. Then the son ofThun mi (Thon mi) A nu, known as Thon mi Sambhota, who had sharper intelligence, a more acute mind, and better qualities than anyone else, and unsurpassed qualities of body, wealth, and accoutrements, was sent to India to learn how to write, carrying a large quantity of gold.

བློན་པོ་དེས་ཀྱང་ལུས་སྲོག་ལ་མ་གཟིགས་པར་རྒྱ་གར་ལྷོ་ཕྱོགས་སུ་ཕྱིན་ཏེ། ཡི་གེའི་སྒྲ་ལ་མཁས་པ་བྲམ་ཟེ་ལི་བྱིན་གྱི་དྲུང་དུ་ཡི་གེ་བསླབས། པཎྜི་ཏ་ལྷ་རིག་པའི་སེང་གེའི་དྲུང་དུ་བསྟན་བཅོས་ཐམས་ཅད་བསླབས་ནས། རིག་པའི་གནས་ལྔ་ལ་མཁས་པར་གྱུར་ཏེ། འདུས་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་ཏོག་གི་གཟུངས་མདོ་ཟ་མ་ཏོགསྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་མདོ་རྒྱུད་ཉི་ཤུ་རྩ་གཅིག་རྣམས་བོད་དུ་བསྒྱུར།

That minister, in his extraordinary life, went to the south of India and he learned grammar at the feet of the learned Brahmin, Li byin; he learned all the religious commentaries at the feet of the Pandita lHa rig pa’i seng ge; he mastered the five sciences.The ʼDus pa rin po che tog gi gzungs mdo,16 the Za ma tog,17 and the twenty-one sūtras and tantras of Spyan ras gzigs were translated into Tibetan.

རྒྱལ་པོ་དགའ་སྟོན་གདན་སར་བྱོན་པ་ལ། ན་རོ། གི་གུ། འབྲེང་པོ། ཞབས་ཀྱུ་སོགས་སྡེ་མཚན་དུ་བྱས་ཏེ། ཡི་གེའི་ཕུད་འདི་ཕུལ་ལོ།

ཞལ་ཟས་གསལ་ལ་དྭངས་པ་གང་བ་བཟང་།

གདམས་ངག་ཟབ་ལ་མ་ཆད་ཐ་དད་རང་།

ལས་ངན་བག་ཆགས་ཐམས་ཅད་བསལ་མཛད་པ།

འཕགས་པ་མ་ཕམ་ཡང་དག་དམ་པ་ལ།

བདེ་གཤེགས་བདེན་ངེས་ཡེ་ཤེས་ཏེ།

ཏིང་འཛིན་བཞི་ཉིད་རིག་ཅིང་གཟིགས།

ཉོན་མོངས་ཚོགས་བཅོམ་མགོན་པོ་མཆོག

དུག་གསུམ་བདུད་འདུལ་ཀུན་ཏུ་ཐུལ།

སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དབང་ཐུགས་གྱི་སྲས།

སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོར་མཚན་གསོལ་པའི།

ཆོས་རྒྱལ་ཁྱོད་ལ་ཕྱག་འཚལ་ལོ།

When he arrived [back] at the king’s feast, at his seat, having created the characters for the naro, gigu, and drengpo, zhabkyu, he offered these choice words (yi ge'i phud):

‘This feast is excellent, full of brightness and light.

There is a ceaseless stream of distinctive, profound advice.

All patterns of bad behaviour are being swept away.

Noble, invincible, authentic, excellent,18

Having attained enlightenment, certain truth, and wisdom,

And knowledge and experience of the four kinds of meditation,

The supreme protector, who triumphs over all afflictions,

Tamer of the three poisonous demons, may you tame everyone.

Powerful and exalted descendant of Spyan ras gzigs,

Bestowed with the name Srong btsan sgam po,

I pay homage to you, dharmarāja’. These were his words of praise.

ཞེས་སྟོད་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོ་ཤིན་ཏུ་མཉེས་ནས། སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་བསྟན་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་ལ་དགོངས་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོས་བློན་པོ་ལ་བཀུར་སྟི་དང་ཕུ་དུད་མང་དུ་མཛད་དོ། ཡི་གེའི་བསྒྱུར་ཚུལ་རྒྱས་པ་གཞན་དུ་གསལ་བས་དེར་ལྟ་བར་བྱའོ།

The king was extremely delighted and thought of the precious teachings of the Buddha. He heaped honour and offerings upon his minister and [ordered that] the means of translation should be disseminated clearly to others.

དུས་དེ་ཙ་ན། ཡོངས་གྲགས་ཀྱི་བློན་པོ་ [14] སུམ་རྒྱ་ཡོད་པའི་ནང་ནས། འཕྲུལ་གྱི་སྣ་ཆེན་རིགས་བཟང་། ཞང་པོ་རྒྱལ་གྱི་ཁྲོམ་བཟང་། ཅོག་རོ་རིགས་པའི་ཁོང་བཟང་། ལྷར་གཟིགས་ཤོག་པོ་བསྟན་བཟང་། བཀའི་སྙག་སྟོན་འཕེལ་བཟང་སྟེ། ནང་བློན་བཟང་པོ་དྲུག་ལ་སོགས་པ་བློན་པོ་བརྒྱ་ཐམ་པས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་སྐུ་ཞབས་ཏོག་དང་ནང་གི་བྱ་བ་ཐམས་ཅད་བྱེད་དོ།ཕྱི་བློན་བཙན་པོ་དྲུག་ནི། ཁྱུང་པོ་སྤུན་བཟང་བཙན། ལམ་ཁྲི་བདེ་ལག་ཁྲི་བཙན། མུ་ཁྲི་རྡོ་རྗེ་རྣམ་བཙན། མཐིང་གི་བྱང་ཆུབ་མཆོག་བཙན། ཐར་པ་ཀླུའི་རྒྱལ་བཙན། རོང་པོ་འཕྲུལ་གྱི་ལྡེ་བཙན་ལ་སོགས་པ་བློན་པོ་བརྒྱ་ཐམས་པ།

At that time, among three hundred renowned ministers, there were six excellent interior ministers, including ʼPhrul gyi sna chen rigs bzang, Zhang po rgyal gyi khrom bzang, Cog ro rigs pa’i khong bzang, lHar gzigs shog po bstan bzang, and bKa’i nyag ston ʼphel bzang. In all, one hundred ministers served the king’s person and conducted all internal affairs. As regards the six powerful ministers of the exterior, they were Khyung po spun bzang btsan, Lam khri bde lag khri btsan, Mu khri rdo rje rnam btsan, mThing gi byang chub mchog btsan, Thar pa klu’i rgyal btsan, and Rong po ʼphrul gyi lde btsan. In all there were one hundred ministers.

ཤར་རྒྱ་དང་མི་ཉག་གི་ཡུལ་ནས་བཟོ་དང་རྩིས་ཀྱི་དཔེ་བླང་། ལྷོ་ཕྱོགས་རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་ཡུལ་ནས་དམ་པ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་སྒྲ་བསྒྱུར། ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་སོག་པོ་དང་བལ་པོའི་ཡུལ་ནས་ཟས་ནོར་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་ཀྱི་གཏེར་ཕྱེ། བྱང་ཕྱོགས་ཧོར་དང་གེ་སར་གྱི་ཡུལ་ནས་ཁྲིམས་དང་ལས་ཀྱི་སྲོལ་བཏོད། མདོར་ན་ཕྱོགས་བཞི་ལ་དབང་བསྒྱུར་ཞིང་ལོངས་སྤྱད་ནས།འཛམ་གླིང་ཕྱེད་ཀྱི་བདག་པོ་མཛད་དོ།

From the east, from China and Tangut (mi nyag), were taken examples of handicrafts and arithmetic; to the south, from India, religious texts were translated; to the west, from Sog po and Nepal, treasuries of food, wealth, and luxuries were opened; to the north, from Mongolia and the land of Ge sar, laws and traditions of working were taken. In this way, by dominating and profiting from what lay in all four directions, he became lord of half the world.

དེའི་དུས་སུ་རྒྱལ་པོ་དེ་ཉིད་ཀྱིས། ང་ནི་ཆོས་སྐྱོང་བའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡིན་པས། ངའི་བཀའ་དང་འཁོར་དུ་གཏོགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། ལུས་ཀྱི་སྒོ་ནས་སྲོག་གཅོད་མ་བྱིན་ལེན་དང་འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱོད་པ་དང་གསུམ། ངག་གི་སྒོ་ནས་རྫུན་དང་ཁྲ་མ(ཕྲ་མ)་དང་ཚིག་རྩུབ་དང་ངག་འཁྱལ་དང་བཞི། ཡིད་ཀྱིས(ཀྱི)་སྒོ་ནས་བརྣབ་སེམས་དང་གནོད་སེམས་དང་ལོག་ལྟ་དང་གསུམ།མདོར་ན་མི་དགེ་བཅུ་སྤོངས་ཤིག བསད་པ་ལ་སྟོང་འདེད་དོ། རྐུས་པ་ལ་བརྒྱད་འཇལ་དངོས་དང་དགུ་འདེད་དོ། འདོད་ལོག་སྤྱད་པ་ལ་བྱི་རིན་འདེད་དོ། རྫུན་སྨྲས་བ་ལ་མནའ་སྒོག་གོ ཞེས་བཅའ་བ་བཞིའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས།

Then the king said, ‘I am a king who protects the religion. My orders for my followers are: as regards the three of the body—killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct; as regards the four of speech—lying divisive speech, harsh speech, and gossip; as regards the three of the mind—covetousness, malice, and wrong views. In brief, you must reject the ten non-virtues. Killing should be followed by blood money; stealing by compensation of eight, together with the object, making nine; sexual misconduct by a fine (byi rin); lying by the administration of an oath’. With the addition of these four, he made the laws.

གཞན་ཡང་ངའི་འབངས་སུ་གཏོགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱི(ཀྱིས)། ལྷ་དཀོན་མཆོག་གསུམ་པོ་ལ་དད་པ་དང་མོས་གུས་བསྐྱེད་པར་བྱའོ། དམ་པའི་ཆོས་བཙལ་ཞིང་སྒྲུབ་པར་བྱའོ། ཕ་ [15] མ་ལ་དྲིན་ལན་འཇལ་བར་བྱའོ། ཡོན་ཏན་ཅན་ལ་ཞེ་མཐོང་ཡོད་པར་བྱའོ། རིགས་མཐོ་བ་དང་རྒན་པར་བཀུར་སྟི་ཆེན་པོ་བྱའོ། ཡུལ་མི་ཁྱིམ་མཚེས་ལ་ཕན་བཏགས་པར་བྱའོ།ཉེ་དུ་དང་མཛའ་ཤེས་ལ་གཞུང་རིང་བར་བྱའོ། བཀའ་དྲང་ཞིང་སེམས་ཆུང་བར་བྱའོ། ཡ་རབས་ཀྱི་རྗེས་བསྙགས་ཤིང་ཕྱི་ཐག་རིང་བར་བྱའོ། ཟས་ནོར་ལ་ཚོད་འཛིན་པར་བྱའོ། སྔར་དྲིན་ཅན་གྱི་མི་རྩད་བཅད་པར་བྱའོ། བུ་ལོན་དུས་སུ་འཇལ་ཞིང་བྲེ་སྲང་ལ་གཡོ་སྒྱུ་མེད་པར་བྱའོ། ཀུན་ལ་ཕྲག་དོག་ཆུང་བར་བྱའོ།19 ཞེས་བཀའ་བསྩལ་ཞིང་། མི་ཆོས་གཙང་མ་བཅུ་དྲུག་གིས་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་གཞི་བཟུང་། གཞན་ཡང་ལུགས་ཀྱི་བསྟན་བཅོས་གསེར་གྱི་ལེ་ཚེ་སྒྲིགས་དང་། གླང་བཀའ་མཆིད་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་གཉིས་གསུངས་ཏེ།

‘Furthermore, my subjects ought to: generate faith in the Three Spiritual Jewels and show them devotion; search for and practise the true doctrine; repay the kindness of their parents; consider the intellect of the wise; show great respect towards those who have good qualities and elders; be helpful to their fellow countrymen and neighbours; be loyal to relatives and friends; speak honestly and modestly; consistently strive to emulate the upper classes; acquire food and wealth appropriately; seek out those who have been kind; repay debts on time and not be dishonest with bre and srang measures; act with minimal jealousy to everyone’.20 By giving this advice, he made the sixteen principles of human conduct (mi chos gtsang ma bcu drug) into the foundation of the law. This is quoted in two śāstras, known as the Gser gyi le tshe sgrigs21 and Glang bka’ mchid.22

རྒྱལ་པོས་བཀའ་བསྩལ་པ་བཞིན་ཐོན་མི་སམྦྷོ་ཊ་དང་། མགར་བ་གདོང་བཙན། འབྲི་སེ་རུ་གོང་སྟོན། ཉང་ཁྲི་བཟང་རྣམས་ཏེ། བཀའི་འཕྲུལ་བློན་བཞི་ལ་སོགས་པ་བློན་པོ་བརྒྱ་ཐམས་ཅད་པས་བར་གྱི་མཁོད(ཁོད)་སྙོམས། བཟང་ལ་བྱ་དགའ་སྟེར། འཐབ་མོ་བྱས་པ་ལ་ཆད་པ་གཅོད(བཅད)་པ། མཐོ་བ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱིས་གནོན།དམའ་བ་ཐབས་ཀྱིས་སྐྱོང་། སྐུ་གསྲུང(སྲུང)་སྡེ་བཞིར་བཅད། ཕུ་རུ(ཕུ་ཆུ)་རྫིང་དུ་དཀྱིལ(སྐྱིལ)། མདའ་རུ(ཆུ)་ཡུར་བར་དྲངས། བྲེ་སྲང་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ། ཞིང་ལ་ལྷུ་རུ་བཅད། མི་ལ་ཡི་གེ་བསླབ། རྟ་ལ་མདོངས་སུ་བྲིས། ལེགས་པའི་དཔེ་སྲོལ་བཙུགས་ཏེ། ཆོས་ནས་ཇི་ལྟར་བྱུང་བ་བཞིན་གྱི་མི་དགེ་བཅུ་སྤངས།དགེ་བཅུ་ཉམས་སུ་བླངས་པ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས། བོད་ཁམས་ཐམས་ཅད་བདེ་སྐྱིད་ལ་ལོངས་སྤྱད་པས་ཆོག་པ་བྱུང་གདའ། དེ་ལྟར་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལ་བརྟེན་པའི་བོད་ཁྲིམས་ཉི་ཤུའི་བཅས་ཡིག་ནི། ཤོ་མ་ར་རུ་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་ནས། རྗེ་བློན་ཀུན་གྱི་ཕྱག་རྒྱས་བཏབ་སྟེ་ཉི་ཟླའི་འོད་བཞིན་ཀུན་ལ་ཁྱབ་པར་མཛད་དོ།།

On the basis of the king’s advice, the four clever ministers, Thon mi sambhota, mGar ba gdong btsan, ʼBri se ru gong ston, and Nyang khri bzang, along with others, one hundred in all, levelled differences and: they gave rewards to the good; they inflicted punishments on those who quarrelled; they subdued the high with laws; they protected the low by various means; they divided the bodyguards into four; they gathered highland water into ponds; they conducted lowland water into channels; they established weights and measures; they divided fields into plots; they taught men how to read; they branded horses; and they established exemplary customs. On the basis of the customs established in this way, the ten non-virtues were rejected and the practice of the ten virtues was established. The whole of Tibet became peaceful and happy and there were ample material resources.

In this way, a text of the twenty Tibetan laws, based on the ten virtues, was finalized at Sho ma ra. It was sealed by the king and all the ministers, and it was disseminated like the light of the sun and the moon.

༈ བཞི་པ་

Fourth

རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དངོས་ལ་འཇུག་ཚུལ་བཤད་པ་ལ། [16] བསྟན་པ་དང་། བྱེ་བྲག་ཏུ་བཤད་པ་གཉིས།

An explanation of the application (ʼjug) of the royal law, itself, in two sections: general instructions and detailed explanation.

དང་པོ་ནི། ཁ་མཆུའི་རིགས་ཀྱི་གཅོད་རྒྱ་བྱེད་པ་ལ། གཟུགས་བཞི་དཔང་བརྒྱད་དྲང་དང་དགུ་ཟེར་བ་ཞིག་འདུག་པ་ལ། བསམ་མནོ་བློ་བཏང་དུས། དྲང་མཁན་ནི། ཁྲིམས་བདག་དང་བར་མི་ལ་ཟེར། གཟུགས་བཞི་ནི་ཉམས་རུས་རྒྱུས་ཆེ་བ། བློ་ཚད་པ། གྲོས་འདྲི་བ། འོག་ཚོད་ལེན་པ་རྣམས་སུ་འདུགདཔང་བརྒྱད་ཟེར་བ་ནི། གཉིས་ཕྱོགས་ནས་མི་གནད་ཆེ་བ་བཞི་ཙམ་རེ་རྒྱུས་ཡོད་ལ་འཇུག་དགོས་པ་གོ། དེ་ལ་བར་པ་བདེ་མོའི་ཐང་། བློ་ཡུས་རི་གཟར་གྱི་རྦབ་(རྦབ་)། གླང་མོ་ཕམ་དོགས་ཀྱི་གཤགས། བདེན་རྫུན་ཟ་འོག་གི་ཐིག རྣ་བ་གཏམ་ངན་གྱི་སྣོད། ཁ་ཤ་ཆང་གི་སྣོད། ཨ་བག(ཨམ་ཕྲག)་ཁྲག་གཟུའི་སྣོད་བྱ་བར་གྲགས་འདུག

Firstly, for making decisions in different types of disputes, it is said that there are four aspects (gzugs) and eight witnesses (dpang) and the drang, making nine. When considering this it is said that the drang can be the legal lord (khrims bdag) or a mediator (bar mi). The four aspects are superior experience, a measured disposition, a questioning attitude, and [capacity] for thorough investigation (tshod len). As for the eight witnesses, from each of the two sides, you should select four key people familiar with the case.

The activities are known as the following: the mediation (bar pa) is an open plain of equanimity; the accusations (blo yus) are a steep mountain slope (avalanche) (rbab); the cow (glang mo) is the argument (acknowledgement)of failure and doubt (pham dogs kyi gshags); the satin measuring string23 is for truth and falsity; the ears are vessels for evil talk; the mouth is a vessel for meat and chang; the front pocket (am phrag) is a vessel for blood (khrag gzu).24

གཉིས་པ། བྱེ་བྲག་ཏུ་བཤད་པ་ལ། ཁྲིམས་བདག་དང་བར་མི་ལ་དགོས་ཚུལ་བཤད་པ། དངོས་བདག་དང་ཁག་ཐེག་ལ་དགོས་ཚུལ་བཤད་པ། གཡུ་འབྲུག་སྒྲོག་པའི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་སོ་སོར་བཤད་པ་དང་གསུམ།

Secondly, the three detailed explanations:

The explanation of what is expected of the legal lord and mediators

The explanation of what is necessary for parties (dngos bdag) and guarantors (khag theg);

The explanation of each of the edicts (zhal lce) of the Turquoise Dragon Proclamation.

དང་པོ་ནི། ཁྲིམས་བདག་དང་བར་མི་བྱེད་པ་དག་གིས། དམ་ཚིག་གསུམ་དང་གཅེས་པ་བཞིའི་སྒོ་ནས་ཁྲིམས་དང་ཁ་མཆུ་བྱེད་དགོས་པ་ཡིན་པས། དམ་ཚིགས་གསུམ་པོ་ནི། བློ་ཡུལ་ཞིབ་པར་ཉན་པ་དང་པོའི་དམ་ཚིག ། དོག(དོགས)་གཅོད་ཐེམས་པ་གཏོང་བ་བར་གྱི་དམ་ཚིག ངང་རིང་ཞབས་སུ་འཇུག་པ་ཐ་མའི་དམ་ཚིག

Firstly, the activities of the legal lord and mediators: there are three commitments (dam tshig) and four values (gces pa), by means of which they should (apply) the law and make decisions (khrims dang kha mchu byed).

As regards the three commitments:

The first commitment is to listen in detail with a discerning mind.

The middle commitment is to resolve doubts definitively.25

The final commitment is to carry out duties patiently.

གཅེས་པ་བཞི་ནི། ཉན་ཡིག་ཁག་ཁུར་མེད་པར་ཞལ་ལྕེ་མི་གཏོང་བ་དང་གཅིག གཉེན་ངོ་ཕྱོགས་ཆ་མེད་པའི་དྲང་པོའི་

གཞུང་26ལ་བསྟན་པ་དང་གཉིས། གཡོ་སྒྱུ་ངན་སྐྱོག་མེད་པའི་འགྲིག་པ་གཙོ་བོར་འདོན་པ་དང་གསུམ། བློ་སྐྱོན་རང་འདོད་མེད་པའི་མཁས་པའི་མི་ལ་འདྲི་བ་དང་བཞིའོ། མདོར་ན་འཚེམས་པའི་ཁབ་དང་།འབྲེག་པའི་གྲི། ལེགས་སྦྱོར་སོར་མོས་འཆང་གི་ཚུལ་ཤེས་པ་གཅིག་དགོས་པ་ལས།

As regards the four values:

The first is, without a nyan yig khag khur,27 do not give an edict.

Second, without [displaying] partiality towards relatives or friends, give correct explanations.28

Third, put forward a principal agreement that is without deceit or falsity.

Fourth, consult wise people who have no wrong views or self-interest.

In brief, you should act dextrously, like someone who knows how to use a sewing needle and a knife.

དེ་ལ་དང་པོ་མཚམས་མིས། དངོས་ཁག་སོ་སོ་འཚོག་པར། འདི་ལྟར་བྱ་སྟེ། མི་ [17] ལུས་གྲུ་བཞི་འདི་སྐྱིད་སྡུག་གི་འབྱུང་ས། ལེགས་ཉེས་མི་ལ་ཡོང་སྟེ་ཉེས་པ་མིས་འཆོས། མཛེར་བ་ཤིང་ལ་ཡོང་སྟེ་སྟ་མོ་དང་སྟེའུས་གཞོག མི་གཉིས་རྩོད་པའི་བར་དུ་མི་གཅིག་བྱུང་བ་དེ། ལྷ་མངོན་སུམ་དུ་བྱུང་བ་ཡིན། འཁྲུག་པ་ལྷའི་ཡུལ་དང་སྡུམ་སྲིན་པོའི་ཡུལ་ན་ཡོད་བྱ་བ་ཡིན། དང་པོའི་ཚིག་ལ་གྱ་ནས་ཐ་མ་རོ་ལ་སྡུམ། མི་ཤ་བརྒྱ་ཕྲག་འདས་ཀྱང་ཐ་མ་སྡུམ་ལ་ལྡོགས། སྡོང་པོ་འགྱེལ་འདོད་དེ་རླུང་ལ་སྐྱོ་བ་ཡིན། ཤ་ཟེལ་ལང་འདོད་ཁྲག་ལ་སྐྱོ་བ་ཡིན། དོན་མེད་པའི་ཁ་མཆུ་འཚོལ་བ་འདི། ཚོད་ཆུང་ནོར་ལ་རྡུལ་དཀྲུག་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན།

So, firstly, a judge (mtshams mi),29 gathering all the facts, ought to act in these ways:

The solidity30 of the human body is the origin of [both] happiness and suffering;

[Both] good and bad happen to people; evil is created by men;

Knots appear in wood; the axe and hatchet chop [the wood];

Between two quarrelling men, one man comes; it is like the advent of a deity.

It is said that fighting occurs in the realm of the deities and reconciliation occurs in the realm of the demons.

If the first words are spoiled (gya pa), you will end up mediating [between] corpses.

Even if the revenge killings surpass one hundred, in the end [the parties] will be reconciled.

Wanting to cut down a tree is a matter of regret for the wind; wanting also to chip away at the flesh is a matter of regret for the blood.

Pursuing a pointless legal case for property of little value is like stirring up dust.

གང་ལྟར་ཀྱང་སྡུམ་བྱེད་པ་ལ། ༢ དང་པོ་བློ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་གཤགས་ཉན་དགོས་པས། སྐབས་འདིར་དངོས་བདག་གིས་གཤགས་འདི་ལྟར་འཕེན་ཏེ། གཤགས་ལ་རིགས་ལྔ་ལས། དང་པོ་འཕེན་གཤགས་མིག་ནག་ནི། གྲོགས་པོ་མི་འགྲོ་བ་ལ་མ་རྒོལ། མི་ཤེས་པ་ལ་མ་འགུགས། མ་ཉེས་བཏབ་ལ་མ་འཆད། ཉེས་པ་སླེ་ལ་མ་འབོར་ཞེས་སོགས་སོ།།༢ གཉིས་པ་ངན་གཤགས་བརྒྱད་གནོན་ནི། ཡའི་ཁ་བྱི་ཁུང་ཙམ་འདིར་གཟུགས། གཉའ་ཤིང་རྩ་འདི་ལ་མ་འཚགས། མི་ཤེས་བྱུས་ཆུང་རང་རྒྱལ་གྱི་བསད་ནས་སྟོང་གསེར་རི་ཁོལ་པོ་ལ་མ་ལེན་ཞེས་སོ། ༢ གསུམ་པ་བརྗིད་གཤགས་ཉེར་ལྔ་ནི། དྲུང་ནས་ཤི་བའི་རོ་ལ་འཚང་མདོ། གསད་པ་ཁྲིས་པ་ཨ་ཁག་ཞེས་སོགས་སོ།

Nevertheless, as far as the mediation (sdum) is concerned, first, it is necessary to listen to the arguments (gshags) of the accuser. At this stage, arguments are flung about by the parties. There are five types of arguments:

First the ‘black-eyed’ (mig nag) forceful arguments (ʼphen gshags): do not oppose it when [the parties] say that friends should not participate; do not summon those who do not know [about the case]; do not exclude someone who claims innocence; do not reject the bad and deceitful (sle)31, and so on.

Second, overcoming the eight bad arguments (ngan gshags): the ya’i kha32 should be put in a mouse hole; do not press down (’tshang) with a wooden yoke; a little ignorance can be vanquished by pride; do not take a mountain of gold from a servant.

Third, the twenty-five arguments about dignity: [one party] asserts the faults of the person killed; [the other party says] the blame rests solely with the killer.

༢ བཞི་པ་ལན་གཤགས་རྩེ་སྙུང་ནི། ཁོ་སྟེ་ཁྱོད་གྱོང་པོ་བཀུག་པས་མི་ཁུགས་པ་ཅིག་འདུག་སྟེ། ང་ཡང་མཉེན་པོ་བཅག་པས་མི་ཆོགས་པ་ཅིག་ཡིན་ཞེས་སོ། ༢ ལྔ་པ་ཆེ་ཐབས་མཐོ་རྒྱལ་གྱི་གཤག་ལ། ཆེ་བའི་རྒྱུ་བཞི། ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས་བཞི། ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན་བཞིའོ། * ཆེ་བའི་རྒྱུ་བཞི་ནི། ཕ་མེས་རུས་རྒྱུད་ཀྱི་ཆེ་བ།བྱས་པ་ལག་རིས་ཀྱི་ཆེ་བ། སྤྱད་པ་སྟོབས་ [18] ཀྱི་ཆེ་བའོ།

Fourth, the arguments in response, and the points being made. [He says] ‘You are stubborn, you do not deserve what you are seizing (demanding); I am compliant, I should not be dashed down’.

Fifth, the arguments of the proud, those of high rank:

The four causes of greatness.

The four signs of greatness.

The four qualities of greatness.

As regards the four causes of greatness:

The greatness of one’s ancestral lineage.

The greatness of the destiny of one’s deeds.

The greatness of powerful resources.

༢ ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས་བཞི་ནི། བཏུང་བ་ཇ་དང་ཆང་ལ་བྱེད་ན་ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས། གོས་སུ་དར་ཟབ་དང་གཡི་སྤྱང་གོན་ན་ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས། ཁལ་དུ་ཇོ་དང་དྲེའུ་ཁོལ་ན་ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས། མགྲོན་དུ་མི་ཆེན་དང་ཐག་རིང་པ་ཡོང་ན་ཆེ་བའི་རྟགས། ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན་བཞི་ནི། བླ་མ་དཀོན་མཆོག་གཙུག་གི་ནོར་བུ་ལྟར་འཁུར་ནུས་ན་ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན།ཕ་མ་དང་རིགས་རྒྱུད་ལྕགས་ཀྱི་ཡོབ་ཆེན་ལྟར་འདེགས་ནུས་ན་ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན། བུ་ཚ་དང་འཁོར་འདབ་བེའུ་ལུ་གུ་ལྟར་སྐྱོང་ནུས་ན་ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན། དགྲ་བོ་ངན་བྱེད་ལ་སྤང་ལ་ཕུར་པ་རྒྱབ་པ་ལྟར་རྡེག་ནུས་ན་ཆེ་བའི་ཡོན་ཏན་ནོ།།

As regards the four signs of greatness:

The sign of greatness is when one drinks tea and chang.

The sign of greatness is when one wears fine silks and wolf or lynx [furs].

The sign of greatness is when one [is able to] carry [loads] like a mdzo or a mule.

The sign of greatness is when one entertains great people and those who come from afar.

As regards the four qualities of greatness:

The great quality of being able to venerate a precious lama as if he were a jewel in a crown.

The great quality of the ability to support one’s parents and family, is like an iron stirrup.

The great quality of the ability to protect one’s children and those around one, as if they were calves and lambs.

The great quality of the ability to strike enemies and evil-doers, as if striking a ritual dagger (phur ba) into the grass.

གཤགས་ངོ་བོ་ནི། སྣོད་བཅུད་ཀྱི་འཇིག་བརྟེན་འདི་ཁྱོད་ཀྱི་ཕ་མའི་རིང་ལ་ཆགས་སམ། ངའི་ཕ་མའི་རིང་ལ་ཞིག ངའི་རིང་ལ་བཙོངས་སམ། ཁྱོད་ཀྱི་རིང་ལ་ཉོས། ཞེས་སོ། དེ་ལྟར་གཤགས་སྒོ་ཉན་ཚར་བ་དང་། ཡང། བར་པས་འདི་ལྟར་བྱ་སྟེ། ཁྱོད་གཉིས་གསུང་འཇམ་པོ་གསུངས་ཤིག གཏམ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་འདི་རྭ་མེད་པར་རྡུང་ཤེས་པ།ཡན་ལག་མེད་པར་ཁྲབ་ཤེས་པ། རྒོད་ཀྱི་རུ་ལ་རྒྱབ་པས། དུང་གི་ཚིལ་བུར་ཕོག་པ། མུན་པ་ལ་མདའ་རྒྱབ་པ་ལྷའི་སྙན་དུ་འགྲོ་བ་ཅིག་དགོས་པ་ལགས་བྱས་ནས། ཉན་ཁག་ཟུར་གཏེའི་བསྡམས་ར་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར་ནས་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན་ནོ།

As regards the essence of the arguments [the mediator should think]: ‘This world and its inhabitants, has it been formed in the time of your parents, or destroyed in the time of my parents? Has it been sold in my time, or bought in your time?’ In this way, you should hear out the opening arguments (gshags sgo).

Then, the mediator should act like this (say): ‘You should both talk gently, and your speech should be like this: knowing how to strike without using your horns; knowing how to perform without using your limbs; after aiming at the bone of the vulture (rgod kyi ru), you shatter the conch into fragments (dung gi sil bu); the arrow shot in the dark reaches the ear of the deity. You should be like this.’

He should take whatever additional promises and guarantees (nyan khag zur gte’i bsdams)33 are appropriate in the situation.

གཉིས་པ་དངོས་བདག་དང་ཁག་ཐེག་ལ་དགོས་ཚུལ་བཤད་པ་ནི། དངོས་བདག་གིས་སྡིག་པ་གསུམ་སྤངས་ཤིང་། གཅེས་པ་བཞི་དང་དགོས་པ་གསུམ་མདོར་བསྟན་པ་དང་བཅས་པ་ཞེས་དགོས། སྡིག་པ་གསུམ་ནི། རྐུན་མོ་གཤགས་ཆེ་བ་དང་གཅིག བྱི་བོ་ཁ་ཁྲེང་བ་དང་གཉིས། བ་སྐམ་རྨོས་བཟང་བ་དང་གསུམ། དེ་གསུམ་རང་ལ་སྡིག་པ་སྤོང་དགོས།གཅེས་པ་བཞི་ནི། སྤྱི་མི་དགྲ་རུ་མི་ལེན་པ་དང་གཅིག རང་མི་བདེན་པའི་གཤགས་མི་འདེབས་པ་གཉིས། བྱ་བ་ཁ་མ་ཐལ་བ་དང་གསུམ། [19] ཁག་ཁུར་མི་བསླུ་བ་དང་བཞིའོ།།

Secondly, the explanation of what is necessary for a party and a guarantor (khag theg).

The parties must avoid the three sins and know, in summary, the explanation of the four values (gces pa) and three necessities (dgos pa).

As regards the three sins:

One, the very argumentative thief.

Two, the serial sexual offender.

Three, ba skam rmos bzang ba.34

These three are the sins that one must avoid.

As regards the four values (gces):

One, in general, not to make enemies of ordinary people.

Two, not to put forward untruthful arguments.

Three, not to go beyond your actions.35

Four, not to deceive your surety (khag khur).

དགོས་པ་གསུམ་ནི། འཇམ་པོ་ངང་གིས་གྲོས་དུས། གསུང་དྲིལ་བུ་བས་སྙན་པ་ཅིག་དགོས། མི་འདྲ་བ་གཤགས་སུ་འཕེན་དུས་ལྗགས་ཕུ་བས་བདེ་བ་གཅིག་དགོས། གཤགས་སྣ་དགོས་དོན་དུ་སྒྲིལ་དུས་མཆུ་སྐྱི་ཚེ་ལས་རྣོ་བ་ཅིག་དགོས།

As regards the three necessities:

Talking gently and naturally, your speech should be more melodious than a bell.

When putting forward contradictory arguments, you should be calmer than the breath of a lama (ljags phu).

By combining the meaning of several arguments, you should be sharper than a beak (mchu skyi tshe).

མདོར་ན་དཔེ་དོན་རྟགས་གསུམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་གཤགས་གྲལ་དུ་གཤགས་འདོན་འདྲ་འཐད་འོས་གསུམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་ནང་དུ་གྲོས་སྤེལ། དགེ་ཡོན་སྐྱོན་གསུམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་ཕ་རོལ་དུ་གོ་སྐོན་སྨོད་རགས་སྦོམ་གསུམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་མཉམ་ཉིད་ལ་གཤགས་རྒྱག མཐོ་དམན་འབྲིང་གསུམ་ལ་བསྟེན་ནས་མདུད་མའི་ཧས་བཀོད་བཤེས་དགོས་སོ།

In brief:

Based on the trio of example, meaning, and sign, you put forward your arguments in stages.

Based on the trio of similarity, agreement, and suitability, you augment the discussion within.

Based on the trio of virtue, good qualities, and fault, you convince the other side.

Based on the trio of blame, coarseness, and gross transgression, you make equally strong arguments.36

Based on the trio of higher, lower, and middle, you discern displays of exaggeration about general (worldly) affairs.

ཁག་ཁུར་ལ་གཅེས་པ་བཞི་ནི། རང་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་ཁག་ཐེགས་དང་གཅིག གཞན་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་སྐྱོན་ཟིན་པ་དང་གཉིས། སྤྲོད་ལེན་ཞབས་འཇུག་ཚང་བ་དང་གསུམ། ཆོད་ཡིག་དག་གཙང་ལོན་པ་དང་བཞི་དགོས་སོ།།

As regards the four values of those who provide guarantees (khag khur):

One, one’s own surety.

Two, capturing the faults of the other side.

Three, allowing for the complete giving and receiving of respect.

Four, arriving at perfectly clear written agreements (chod yig).

༈ གསུམ་པ་གཡུ་འབྲུག་སྒྲོག་པའི་ཞལ་ལྕེ་སོ་སོར་བཤད་པ་ལ། བསད་པ་སྟོང་གི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། རྨས་པ་ཁྲག་གི་ཞལ་ཆེ། རྐུས་པ་འཇལ་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ། བསྙོན་ཅན་མནའ་བཀར་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ། བྱི་བྱས་བྱི་རིན་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ། བྱེ་བྲལ་མཐུན་སྡེབས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། འབྲོས་འདེད་ལེན་ལན་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ། དམའ་ཕབ་ཡུས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ།དཔུས་འདོད་ཚོང་གི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། ལྷག་ཆད་རྩིས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། ལ་ལྷོ(ལྟོ)་རྒྱབ་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། ནམ་ཕར་ཚུར་གྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། དཔའ་བོ་སྟག་གི་ཞལ་ལྕེ། རྡརྨ་བའི་(སྡར་མ་ཝའི)་ཞལ་ལྕེ། ཁྲིམས་འདེགས་བབས་སྙུག་གི་ཞལ་ཆེ་དང་བཅོ་ལྔ་སྟེ།37

Thirdly, the explanation of each of the edicts of the Turquoise Dragon Proclamation:

The edict on compensation for killing; the edict on blood-wounding; the edict on compensation for theft; the edict on oaths [to counter] deception; the edict on payment for sexual misconduct; the edict on harmonizing those who have separated; the edict on pursuit and revenge; the edict on public insults; the edict on valuing merchandise; the edict on calculating additions and reductions; the edict on food and clothing; the edict on borrowing; the edict on the tiger hero; the edict on the [fox] coward; the edict on court assessors and scribes, making fifteen.

རྒྱལ་བློན་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་ལ་ཚད་མར་བྱེད་ན་དེ་ཁོ་ན་ལྟར་རོ།

This is how to act correctly [in accordance with] the writings of the king and the ministers.

༈ དང་པོ་བསད་པ་སྟོང་གི་ཞལ་ཆེ་ནི།

First, the edict on compensation for killing

ཧོར་ལུགས་དང་བོད་ལུགས་གཉིས་ལས། ཧོར་སྲོག་ཚབ་ཏུ་སྲོག་གཏོང་བས་མི་ཤ་ལེན། བོད་(དུ་)ཆོས་དར་ཞིང་ཆོས་ལ་དཀར་ [20] བས་སྲོག་ཚབ་ཏུ་སྲོག་བཏང་ན་གཉིས་ཕུང་སྡིག་པའི་རྩ་བར་འགྲོ་བས། སྟོང་འཇལ་ལེན་བྱེད་པ་ལེགས་ཟེར་ནས། དེས་ན་སྐལ་པ་སྟོང་པས་སྟོང་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་བྱུང་། དེ་ལ་སྔོན་གྱི་དུས་ན་མི་དྲག་པ་ལ་འཇལ་སྲང་སྟོང་དང་ཞོ་སྟོང་དུ་སྤྲོད་པས་ན་སྟོང་ཞེས་བྱའོ།ཁག་ཁུར་གྱི་ངོ་ཆེན་དང་ཟུར་པའི་ངོ་ཆེན་ལ་ཞུ་ཆག་གཏོང་དགོས་པ་ཡོང་བས་ན་སྟོང་ཞེས་ཟེར། དེས་ན་སྟོང་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་སྟོང་པ་ཡིན་པས་ན། སྟོང་ལེན་ཕྱུག་པོར་སོང་བའང་མེད། སྟོང་འཇལ་སྤྲང་པོར་སོང་བའང་མེད།

Concerning the Mongolian (Hor) and Tibetan traditions: the Mongolian is that through taking a replacement life, revenge is enacted; in Tibet, the Buddhist dharma has spread and because people are oriented towards the dharma, if one takes a replacement life, that is [considered to be] the root of a double sin, so it is said that it is good to accept compensation (stong ʼjal).

It is because [the victim] is empty of fate that this action is called stong (empty);38 and because, in former times, for a nobleman a thousand ʼjal srang and a thousand zho were given, it is called stong (a thousand). Since it has become necessary to petition men of influence—whether with official responsibilities or not—for a reduction, it is called stong. Thus, since the so-called stong is empty, it is said: ‘If you receive stong you do not become rich; if you give stong you do not become poor.’

བྱ་བར་གྲགས་འདུག་པས། རོ་དོས་མཉམ་གྱི་མཇལ་ཡིན་པས་ན་རོ་དོས་ཀྱང་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་སྟེ། སྟོང་དང་རོ་དོས་དོན་གཅིག་པས། མི་དྲག་ཞན་ལ་དཔགས་པའི་སྟོང་སྤྱོད་ལུགས། ས་སྐྱ་པནྡི་ཏས།

རྟ་བརྒྱ་གླང་སྟོང་མི་ཁྱད་འབུམ།

ཡོན་ཏན་ཅན་ལ་བརྗོད་དུ་མེད།

བྱ་བའང་གསུངས་འདུག་ཅིང།

འཇིག་རྟེན་རྒན་པོའི་ངག་ལས་ཀྱང།

སྟོད་ཡ་རྩེ་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཧོར་གྱིས་བསད།

སྤུར་དང་གསེར་ལ་མཉམ་འདེགས་བྱས།

སྨད་གེ་སར་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལྡན་མས་བསད།

ད་དུང་སྟོང་གཞུག་འཕྲོད་པ་མེད།

ཅེས་པ་དང།

ཡ་ཕོ། མགར་བ། ཤན་པ་གསུམ།

བསད་ཀྱང་སྟོང་ལ་དྲེས་ཐག་གཅིག

ཅེས་བྱ་བར་གསུངས་གདའ་བས།

Because it is compensation for death, it is called ‘the burden of death’ (ro dos). Stong and ro dos have the same meaning.

The means of approaching compensation depends on social status. Sa skya PaNDita said:

One hundred horses, one thousand cattle, one hundred thousand ordinary things;

For someone with great qualities, it is unquantifiable.

And, according to the oral traditions of the world’s elders (’jig rten rgan po):

In the west, the Ya rtse king was killed by the Mongols (Hor);

His corpse was weighed for its equivalent in gold.39

In the east King Ge sar was killed by lDan ma,

[But] compensation has still not been given.

And

The vagabond (ya pho), the blacksmith, and the butcher, all three;

If they are killed, compensation is a grass rope (dres thag).

དུས་དེ་ཙ་ན། མི་ཕལ་པ་རང་ཁག་པའང་རབ་འབྲིང་ཐ་གསུམ་ལས། རབ་ལའང་རབ་ཀྱི་རབ། རབ་ཀྱི་འབྲིང་། རབ་ཀྱི་ཐ་མ་དང་གསུམ། འབྲིང་ལ་ཡང་འབྲིང་གི་རབ། འབྲིང་གི་འབྲིང་། འབྲིང་གི་ཐ་མ་དང་གསུམ། ཐ་མ་ལ་ཡང་ཐ་མའི་རབ། ཐ་མའི་འབྲིང་། ཐ་མའི་ཐ་དང་གསུམ་ཡུད་པ་ལས། རབ་ཀྱི་རབ་ལ་བརྒྱ་དང་བཅུ་འམ་བཅོ་ལྔ་སྐོར།དེ་འོག་རབ་ཀྱི་འབྲིང་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་དགུ་བཅུ། དགུ་བཅུ་གོ་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་རབ་ཀྱི་ཐ་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་བརྒྱད་བཅུ། བརྒྱད་ཅུ་གྱ་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་འབྲིང་གི་རབ་ལ་སྟོང་ [21] སྲང་བདུན་བཅུ། བདུན་ཅུ་དོན་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་འབྲིང་གི་འབྲིང་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་དྲུག་བཅུ། དྲུག་བཅུ་རེ་ལྔ་སྐོར།དེ་འོག་འབྲིང་གི་ཐ་མ་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་ལྔ་བཅུ་ང་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་ཐ་མའི་རབ་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་བཞི་བཅུ། བཞི་བཅུ་ཞེ་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་ཐ་མའི་འབྲིང་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་སུམ་ཅུ། སུམ་ཅུ་སོ་ལྔ་སྐོར། དེ་འོག་ཐ་མའི་ཐ་མ་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་ཉི་ཤུ། ཉི་ཤུ་རྩ་ལྔ་སྐོར།

At that time, ordinary people formed three statuses: high, middle, and low:

The high consisted of three: the highest of the high, the middle of the high, and the lowest of the high.

The middle consisted of three: the highest of the middle, the middle of the middle, and the lowest of the middle.

The low consisted of three: the highest of the low, the middle of the low, and the lowest of the low.

For these the [amounts of] srang compensation were: for the highest of the high, between 110 and 115; for the middle of the high, between 90 and 95; for the lowest of the high, between 80 and 85.

Below that, for the highest of the middle, between 70 and 75, for the middle of the middle, between 60 and 65, for the lowest of the middle, between 50 and 55.

Below that, for the highest of the low, between 40 and 45, for the middle of the low, between 30 and 35, for the lowest of the low, between 20 and 25.

བུད་མེད་བསད་པ་ཆེར་མི་ཡོང་། གལ་སྲིད་བསད་པ་བྱུང་ན་སྟོང་སྲང་བཅོ་ལྔ་ནས་བཅུའི་བར་གྱི་འཆར་གོང་དང་རིགས་འགྲེ། བྱིས་པ་ལོ་བརྒྱད་མན་གྱི་གྲི་རྒྱབ་ནས་ཤི་བ་ལ་དགེ་འཐུད་མ་གཏོགས་སྟོང་གི་སྲོལ་མེད་ཟེར། ཡང་། རྐུན་མོ་རྐུ་རུ་ཡོང་པ་ནོར་བདག་གིས་བསད་པ་ལ་སྟོང་གི་ཐོབ་ཐང་མེད་ཟེར་ནའང་རྐུན་མ་སུས་རྐུས་ཀྱང་གཤགས་རོས་གདབ་བྱ་བ་འཇིག་རྟེན་དུ་གྲགས་འདུག་པས།དགེ་ཆས་ཀྱི་འཆར་ཐོབ་པ་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར། ཡང་། བཟུང་བསད་བྱས་པ་དང་། མི་དཔུང་བྱས་ནས་བསད་པ་ལ་སྟོང་རང་ལྟས་བཅད་པ་དེ་འདབ་བཅོད(གཅོད)་པས། སྡེ་སྲིད་རིན་པོ་ཆེའི་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ཡིན་པའང་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར། ཡང་། གསོད་པ་བྱས་ཟེར་བ་དང་། དུག་གཏོང་བ་བྱས་ཟེར་བ་ལ། དག་པ་བྱས་ནས་མ་ཐོན་ན།ཕྱེད་སྟོང་གི་བཤགས་སྲོལ་ཡོད། ཡང་སྟོང་གི་ཚབ་ལ་ཞིང་དྲག་པ་ལ་རོ་མཐོ་འཛུགས་པའི་སྲོལ་ལུགས་ཀྱང་ཡོད།

Women are not often killed. If one is killed, the arrangement (’char) is according to the pattern above, but 15 to 10 srang less. If a child of fewer than eight years is stabbed, it is said that—except for a dge ’thud for the death40—there is no life-compensation.

Further, if it is alleged that a thief has been killed by the property owner, then [his family] is not entitled to compensation. Whoever the thief was, it is said, his corpse will provide the judgment. An appropriate arrangement for the dge chas [should still] be reached.

Further, if someone is killed while being captured, or by a crowd, the stong is decided according to his own price.41 This is in accordance with the legal practices(khrims lugs) of the Sde srid rin po che.

Further, if there is an allegation of killing by poisoning, but it is not proven after investigation,42 it is the custom to decide on half compensation.

Further, as an alternative to compensation, there is a tradition of giving a good field [marked by] a commemoration cairn (ro mtho).43

ད་ཙ་ན་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ལ་རྩི་མཁན་ཉུང་། དེ་ལྟར་སྟོང་གི་རིམ་པ་རྣམས་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར་བ་ཅད་པའི་སྟེང་ནས། ༸གོང་མ་ཆེ་བཙུན་གྱི་ངོ་ལ། སྟོང་སྲང་རྗེས་བཅས་ཆག་བཅུག་ཟེར་བའི་གོང་ཕུད་ཀྱི་ཆར་ཡང་སྲོལ་ལུགས་ལྟར་བྱེད་དགོས། སྡིག་གླ་གྭྲ་ཕུད་བཅུ་ཟུར་འཆག ཡང་དེའི་ཕྱེད་སྙིང་གནོན། དགེ་ཆས་ཀྱི་སྐོར།དགེ་ལ་སྦྱོར་བའི་ཆས་ཡིན་པས་དགེ་ཆས་ཞེས་ཀྱང་བྱ། རོ་བསྡུར་བའི་ཆས་ [22] ཡིན་པས་ན་རོ་ཆས་ཞེས་ཀྱང་བྱ། དགེ་ཆས་དང་རོ་ཆས་དོན་གཅིག་པས་སྟོང་སྲང་དུ་སྤྲད་ཀྱི་སྲང་རེའི་སྟོང་དུ་ནས་ཁལ་རེ་མ་འབྲངས་པ་དང་། མར་གྱི་སྐོར་ནས་ཀྱི་འདབ་བཅོད་བྱེད་པ་དང་། བཞི་ཟུར་བྱེད་པའི་སྲོལ་ལུགས་གསུམ་ཡོད་པ་གང་དགོས་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར།དུས་དེང་སང་ནས་ཁལ་རེ་ལ་མར་ཉག་དོ་མ་སྲོལ་འཛུད་ཀྱི་འདུག རོ་ཁེབས་དང་རོ་འཚོ། ཁྲག་ག་ན་ཅི་འོས་རིག་པས་བཅད། རོ་སྐོར་ཟེར་བ་རོ་སྲེག་པ་སོགས་ཀྱི་དགོས་(དགེ་)ཆའི་སྐོར་ལ་ཟེར་བ་ཡིན་པས། གང་འོས་ཅི་འཆར་བྱེད།

Nowadays, the evaluators (rtsi mkhan) [who know] the legal practices (khrims lugs) are few. They decide on the appropriate stages of compensation, according to the circumstances. According to customary practices (srol lugs),the first portion of the stong srang, the gong phud, must go to the noblest and imperial [legal authority] (gong ma che btsun),44 and this is called the rjes bcas chag bcug. The payment to the monks for the sin (grwa phud) is one tenth. One half of this is the dge chas, which is appeasement for suffering (snying gnon). Since it concerns the acquisitionof merit (dge), it is called the (dge chas). Things for the corpse (ro bsdur) are called the ro chas. The dge chas and the ro chas are the same thing.

One nas khal is given in relation to each srang awarded in compensation,45 or for butter the value is determined in terms of barley, or it is one quarter.These are the three customs. Whichever is appropriate is applied. Nowadays, there is an established custom that each nas khal is [worth] two nyag of butter.

[You must] decide what is suitable for the corpse covering, the ro ’tsho, and the bier (khrag gdan). For the things concerning the corpse, called the ro skor, the pyre, and so forth, make whatever arrangement (’char) is appropriate.

མི་གསོད་དཀར་ནག་ཁྲ་གསུམ་ཞེས་པ། གྲི་སྲི་གནོན་པའི་ལྕགས་གཅོད་ཀྱི་ཆས་ལ་ཟེར་བ་ཡིན་པས་སྐབས་དང་སྦྱར་བའི་འཆར་བྱེད་དགོས་སོ། ཡུག་པའི་མཆི་འཕྱིད། སྐྲ་འཁྲུད། གྲང་དན་ཟེར་བ་དོན་གཅིག་སྟེ་མིང་འདོགས་མི་འདྲ་ག་ང་། དྭ་ཕྲུག་གི་རྒྱགས་རྟེན་ཨ་མའི་སེམས་གསོ། མི་བདག་གི་རྒྱལ་རྣམས་ཇི་ལྟར་འོས་རི་མོ་ཟུར་དུ་འབྲི། གཞན་ཡང་།མི་རབས་འདུན་མའི་སྣེ་འཛིན། ཕ་ཚན་སྤྱིའི་རྒྱལ་ལི། སྤུན་ཟླའི་སྙིང་གནོན། ཞང་ཚན་སྤྱིའི་རྒྱལ་ལི། ཤ་ཉེའི་རྒྱལ་ལི། མག་པའི་གཞུ་འབེབས་ཟེར་བ་སོགས་ཁ་མཆུའི་ཡན་ལག་གི་མིང་འདོགས་མང་པོ་ཡོད་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱང་ཇི་ལྟར་འོས་རི་མོ་ཟུར་དུ་འདྲི། དེ་མ་ཤར་ན། རོ་བདག་གིས་གསོད་མཁན་ལ་རྩོད་དུ་ཡོང་བས།དེའི་རིགས་ཀྱི་མཐའ་འགོགས་དགོས་སོ།

It is said that killing can be white, black, or grey.

An appropriate arrangement (’char) must be made for what is known as the chas of the (gri gnon pa’i lcags gcod).46

The wiping of the widow’s tears,47 the washing of the hair, and the cold seat (grang gdan); have one meaning but different names. The sustenance for orphans, the healing of the mother’s mind, the payment (rgyal) for the head of the family, whatever is appropriate is written down separately.

Further, [for] the leaders of [the following] groups: what are known as the rgyal li of paternal relatives, the appeasement of brothers, the rgyal li of maternal relatives, the rgyal li of general relatives, the mag pa’i gzhu ’bebs, 48 and so on. There are many names given to these types of claims (kha mchu)49 and whatever is appropriate is written down separately. If you do not do this, the victim’s family (ro bdag) will argue with the killer, and you must bring this to an end.

མི་བསད་པའི་རོ་ཆས་སྔོན་ལ་སྤྲོད་པ་དང་། ལེན་པ་དེ་ཕན་ཚུན་གཉི་ཀར་ཁྱེ་ལེན་ཆེ་བ་ཡིན། སྤྲོད་མཁན་ལ་འདབ་ཁྱད་དུ་འགྲོ་བའི་ལུགས་ཡོད། ལེན་མཁན་གཤིན་པོ་ལ་སྙིང་བརྩེ་བ་དང་། དུགས་པ་ཡོད་ན་གཤིན་པོ་ཞག་མ་འགྱངས་པར་བདུན་དང་པོ་ཚུན་ལ་རྣམ་ཤེས་བར་དོར་འཁྱམ་པའི་དུས། ས་ལམ་གྱི་བར་ཆད་རམ་མདའ་[23] ལ་དགེ་བ་བྱས་ན་འགྱུར་ཆེ་བས། ལེན་མཁན་ལ་ཁྱད་ཡོད། ད་ལྟ་གཤིན་པོ་ལ་མི་བྱམས་པའི་འདོད་པ་ཅན་འགའ་རེ་འདབ་ཁྱད་དུ་འགྲོ་བ་དེ་མི་འདོད་པར་མི་ལེན་ཟེར་བ་འདུག་སྟེ། སྟིང་དུ་མར་ནས་རང་སྤྲོད་མཁན་མི་ཡོང་བས།

The ro chas for the victim is first paid over and accepted; for both, this is an important exchange. There is a tradition that the giver handles this separately (khyad du). For the receiver, if he has love and affection for the deceased and, for up to a week—when the consciousness of the deceased is wandering in the bar do—he performs virtuous actions to help [the deceased] [pass] the obstacles of the path, that will make a great difference. [Compensation for this] is [given] separately to the receiver. Now, certain people who dislike the deceased say that they do not wish this to be handled separately, and this is known as ‘non-taking’. As a result of this considerable disrespect, the giver, himself, will not come.50

སྲང་གྲངས་གང་འདུག་དངོས་པོ་གོང་ཐང་གཅོད་ལུགས་སྨར་དང་དཔུས་གཙང་འདབ་། དཔུས་གཙང་དང་ཟོང་འདབ་ཁྱད་དུ་བྱས་ནས་སྤྲོད་ལེན་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན། མི་དྲག་པ་ལ་སྟོང་ཐུན་གསུམ་དུ་བཅད་པའི་སུམ་ཆ་སྨར་དུ་སྤྲོད་པའི་ལུགས་ཡོད་པས། སྔར་སྲོལ་རོ་ཆས་ཀྱི་མར་ནས་དེ་སྟོང་དུ་འདབ(ལྡབ)་ཏུ་གཅོད་པ་ཡིན།གྲི་བཤད་འགུགས་པ་ལ། གསོད་གྲི་རང་ངོས་པོ་སྤྲད་ནས། གྲི་བཟང་ངན་གང་ཡིན་ཀྱང་། སྟོང་གི་ཐུན་གསུམ་གྱི་སྟེང་ནས་སྲང་གང་གཅོད་པ་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ཡིན། མི་ཤ་ལོན་པའི་རྟེན་འབྲེལ་ཡང་ཡོད་ཟེར། ཕལ་ཆེར་མི་སྤྲོད་པ་མང་།

There are means of deciding the value of the goods [to be distributed], according to the number of srang. After the amount and quality of the smar and the goods is separately established, the giving and receiving take place. For a high-status person there are three parts to the compensation and the practice is for one third of what is decided (awarded) to be given in smar. Formerly, the custom was to give butter or barley for the ro chas in addition to the stong.

If the knife has been called for and the actual killing knife is handed over, then whatever its quality, it is the custom for one srang to be deducted from the three parts of the compensation.

There is a practice of rten ’brel called mi sha lon pa,51 but it is often not given.

སྤྲོད་ལེན་སྟོང་ནག་གི་དཔུས། རི་ཕྱུགས། ཀླུང་ཕྱུགས། རྟ་བོང་ན་གཞོན་ནོར་ཉན། གོ་ཁྲབ། དར་རས། སྣམ་ཕྲུག། ལྷོ་ཟོག། བྱང་ཟོག། ཡུལ་ཟོག་སོགས་ལ་ཐུན་གསུམ་གྱི་རིན་རྒྱག་བྱས་པའི་སྤྲོད་ལེན་བྱེད་ཅིང་། དེ་ལ་རིན་ལ་མི་འཆམས་པས། ལག་སྤྲོད་ཀྱི་སྨར་ཞོ་དང་། སྨར་གྱི་སྟོང་སྲང་འཐབ།ལག་སྤྲོད་ཀྱི་རྦད་ཞོ་དང་། རྦད་ཀྱི་སྟོང་སྲང་འཐབ། དེར་མ་ཟད་སྟོང་སྟེང་སྨར་ཟོང་བརྒྱད་འདབ་བྱེད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ཡིན། དེས་ན་གཤགས་རས་མ་ཡིན་པའི་རས་པོ་ཏི་ལྟ་བུ་ཁྲུ་བཅུ་དྲུག་མ་ལ་སྨར་ཞོ། བཅུ་གཉིས་མ་ལ་རྦད་ཞོ། བརྒྱད་མ་ལ་ཟོང་ཞོ་དང་ར་ཕད་བརྒྱད་མ་ལ་སྨར་ཞོ། བཞི་མ་ལ་རྦད་ཞོ། གཉིས་མ་ལ་ཟོང་ཞོར་བྱས་པ་ལ་ཆ་བཞག་ནས་སྤྲོད་ལེན་བྱེད་ཅིང་།གཞན་ཡང་སྨྱུག་མ་སྟོང་ཁྲེས་ལ་སྟོང་སྲང་གང་། ཐོང(གཏོང)་འགུགས་ལ་ཞོ་ཕྱེད་རྣམས་སུ་གཅོད་པ་ཡིན་ནོ། དགེ་ [24] ཆས་ཀྱི་ནས་ནས་ས། མར་མར་སར་གང་ཁྱེར་བྱས་པའི་ལྷག་ལ། གསེར་དངུལ། གོས་དར། ཁྲོ་ཟངས་རྣམས་ལ་མར་ནས་ཀྱི་རིན་རྒྱག་བྱས་པའི་སྤྲོད་ལུགས་བྱེད་པ་མཁས་པའི་ལུགས་ལ་ཡོད་དོ།།

The nature of the ‘black compensation’ given and received includes mountain cattle, plains cattle, riding horses and donkeys, armour, silk cloth, woollen cloth, southern merchandise, northern merchandise, local merchandise, and so forth. These are given and received to achieve the value of the three parts [of the compensation]. If the price is not agreed, it is possible to give lag sprod kyi smar zho and smar gyi stong srang; or lag sprod kyi rbad zho and rbad gyi stong srang. Moreover, there is a legal custom of eight smar and goods, on top of the compensation.

According to the decisions about what is not cloth, but ras po ti,52 the cubit (khru) is sixteen smar zho, twelve rbad zho, and eightzong zho; the ra phad,53 is eight smar zho, four rbad zho, and two zong zho. What is given and received is based on this.

Further, for the smyug ma and the khres one stong srang,54 and for sending and summoning, half a zho is decided upon.

For the dge chas, as an alternative to barley and butter, gold, silver, fine clothes, and copper pots [can be given], to the value of the barley and butter. This method of giving is the method [ordained by] knowledgeable people.

༈ གཉིས་པ་རྨས་པ་ཁྲག་གི་ཞལ་ཆེ་ནི།

Second, the edict on blood-wounding

སྔོན་གྱི་དུས་ན། མི་རབ་ཁྲག་ལ་ཐིགས་ཞོ་དང་། མི་འབྲིང་ཁྲག་ལ་ཐིགས་སེ་དང་། མི་མཐའ་ཁྲག་ལ་ཐིགས་བྲེ་ཟེར་བ་ཅིག་གྲགས་གདའ་ནའང་། ད་ཙ་ན་འཐབ་རྩོད་བྱུང་བའི་རྩ་བ་ལ་བདེན་པ་ཆེ་ཆུང་། རྨས་ཚབས་ཆེ་ཆུང་མཐའ་ཆོད་བྱས་ཏེ། ཤ་རྒྱབ་ཏུ་ནས་ཁལ་གཉིས་མའི(མེ)་ཤུལ་དུ་དཀར་ཤ་རེ། མར་ཉག་ལྔ། ཚྭ་བྲེ་རེ།མར་ཁུ་ཕུལ་དོ་ཙམ་ལ་ལྷུ་བླངས་ནས། རྨས་གོས་ཁྲག་གདན། རྒྱལ་དང་བཅས་པ་ཇི་ལྟར་འོས་རིགས་པས་གཅོད།

In former times, there was a well-known saying: ‘for (shedding) the blood of a high-status person, one zho, for (shedding) the blood of a middle-status person, one se, for (shedding) the blood of a low-status person, one bre’. However, nowadays a decision that goes to the root of a dispute is made according to the extent of the truth and the severity of the wounding. For striking someone’s body (sha rgyab tu), two khal of barley; for a burn (me shul), white meat; five nyag of butter; one bre of salt; about two phul of clarified butter. When these portions have been accepted, a considered judgement (rig pas gcod) is made on the bandages (rmas gos) and bedding [for the injured person], together with the penalty (rgyal)—whatever is appropriate.

རྨ་ཚབས་ཆེ་བའི་ན་ཡེ། ཤི་ཡེ་འདབ་གཅོད་ཀྱི་སྲང་གྲངས་དང་ཞོ་གྲངས་གཅོད་ན། འཇལ་འདབ་ལ་སྨར་ཟོང་ཕྱེད་མར་གཅོད་པའི་ལུགས་ཡིན། ཡང་། རྨས་ཚབས་ཆེ་བ་ལ་མེ(མིའམ་རྨས)་གྲངས་སོགས་དགོས་པ་བྱུང་ན། རྨ་གོས་ཁྲག་གདན་ཇི་ལྟར་འོས་པའི་སྟེང་དུ་ཐུན་གསུམ་གྱི་མེ་ཤུལ་དུ་ཞོ་དང་། དྲས་ཤུལ་དུ་སྲང་།རུས་པ་ཐོན་པ་ལ་གསེར་དངུལ་གྱི་བརྒྱད་སྐོར་བྱེད་པ་དང་། རུས་པ་རེ་ལ་ཐོན(ཐུན)་གསུམ་གྱི་སྲང་རེ་བྱེད་པ་ལུགས་གཉིས་ཡོད་པ་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ལྟར་བྱེད་ཅིང་།

In the case of a serious wounding, which leaves someone as good as dead (na ye shi ye), the amounts of srang and zho are decided upon and it is the custom for one half [to be paid] in smar and goods. Further, for serious wounding, if it becomes necessary to do a calculation for burns and so on, in addition to what is appropriate in terms of the bandages and bedding, there are three stages: a zho for a burn mark (me shul), a srang for a scar (dras shul), and about eight of gold and silver for a visible bone; for each bone, srang for each of the three stages are calculated. There being two systems (lugs gnyis), this is done in accordance with the legal custom (khrims lugs).

རྒྱལ་ཤ་ཆང་གི་གྲངས་ཁ་དང་། ཟོང་གི་རྣམ་གྲངས་མང་ཉུང་གང་དགོས་རིག་པས་གཅོད། དེ་ལའང་རིན་ལ་མི་འཆམས་པས། ཤ་ནི་སུམ་ནལ་མ་ལ་ཆང་ཁལ་ཕྱེད་མ། ཀོ་ལེ་ཞོ་རེ་མ། སྤང་ཁེབས་གསུམ་ནལ་མ་ཞྭ་སྦྲེལ་བུབས་ཞོ། སླེལ་ཁྲ་གསུམ་ནལ་མ། བལ་རས་བཞི་ནལ་མ། སྟག་སྲང་ཕྱེད་མ། གཟིགས་ཞོ་མ། གུང་ཞོ་རེ་མ་ཙམ་གཅོད་དགོས།

A considered judgement is made on the calculation of the penalty, in meat and chang, and the quantities of goods, whatever is necessary. In that regard, since there will be disagreement about the value of the goods, it must be decided [in this way]: regarding meat, three nal ma; for chang, half a khal; for the ko le, one zho; for aprons, three nal ma; for the cloth to cover a hat, one zho; for a basket (slel khra), three nal ma; for woollen cloth, four nal ma; for a tiger [hide], half a srang; for a leopard [hide], one zho; for a wild cat (gung) [hide], one zho.

༈ གསུམ་པ་བརྐུས་པ་འཇལ་གྱི་ཞལ་ཆེ་ནི།

Third, the edict on compensation for theft

ཆོས་རྒྱལ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ་དེ་ཉིད་ [25] ཀྱིས། རྐུས་ན་བརྒྱད་འཇལ་དངོས་དང་དགུ་འདེད་དོ། ཞེས་བྱ་བ་གསུངས་ནའང་། ད་ཙ་ན། སྡེ་སྲིད་མི་གཅིག་པའི་ས། གཞན་གྱི་ས་ནས་ཇག་རྒྱབ་པ་ལྟ་བུ་ལ་བདུན་འགྱུར་ངོས་བརྒྱད་འམ་འདྲ་བཞི་དངོས་དང་ལྔ་སྡེ། སྡེ་སྲིད་གཅིག་པའི་ས། གཞན་གྱི་ས་ནས་རྐུས་པའི་འཇལ་ཆེ་བ་ལ།འདོགས་གསུམ་དངོས་དང་བཞི། ཆུང་བ་གསུམ་འདོགས་སམ། སྐྱེ་འཁྲིགས་ཆགས་གསུམ་མོ། རྒྱལ་འདོགས་དངོས་དང་གསུམ་ཞེས་པ་དོན་ཅིག་ལ་མིང་འདོགས་མི་འདྲ་བའི་གཅོད་རྒྱ་བྱེད།

The Buddhist king Srong btsan sgam po, himself, said, ‘if someone steals, there should be eight-fold compensation (’jal), together with the actual object, making nine’.

Nowadays, in the province of one sde srid, if the bandit is from elsewhere, an addition of seven, with the object becomes eight; if he is from the same, four becomes five. In one province, the high compensation for thieving (sku pa’i ’jal) from another place is an addition (’dogs) of three, with the object making four; the lesser [compensation] is an addition (’dogs) of three; or the accumulated interest (skye) is three. The penalty (rgyal), addition(’dogs), and object (dngos) have a single meaning but different names in the settlement of disputes.

ཁྱིམ་ཚེས་ཕན་ཚུན་རྐུ་རེས་བྱས་པ་ལ། དངོས་པོ་གང་ཡིན་དེའི་མགུལ་འདོགས་རྒྱལ་འོས་རིགས་དང་བཅས་པས་བཅད་ནས། རྫས་ངོ་ནོར་ངོ་། མི་ངོ་སོགས་ཀྱི་ཕྱིར་མི་གཏོང་བར་ཁྲིམས་གཞུང་སྲོང་ལ་གལ་ཆེ། དེ་ལྟར་རྐུ་འདོགས་ཀྱི་རིམ་པ་སྐབས་ཐོབ་དང་སྦྱར་བ་བཅད་པའི་སྟེང་ནས། ངོ་ཚ་སྤྲད་རིན་ལ་འདི་བྱིན་བྱ་བའི་གོང་ཕུད་ཀྱི་འཆར་ཡང་བྱེད་དགོས་སོ།དགེ་འདུན་གྱི་སྤྱི་རྫས་རྐུས་པ་ལ་གནས་དབྱུང་ལྟ་བུ་དང་། དཀོན་མཆོག་གི་བརྒྱད་ཅུ་འཇལ་དང་། སྡེ་དཔོན་གྱི་གན་མཛོད་ནས་རྐུས་པ་ལ་ཁས་དྲག་གི་དགུ་ཅུ་འཇལ་དང་། ཡང་ན། མིག་སྒྱིད་ལག་གསུམ་ལ་བབས་པ་ཀ་མང་ངོ་།

In the case of theft between neighbours, whatever the objects, a suitable mgul ’dogs penalty is decided upon. For material goods, wealth, men of importance, and so forth, it is important to apply the (governmental) laws (khrims gzhung) correctly. Thus, whatever is decided upon as an appropriate rku ’dogs, an arrangement for a gong phud must also be made, for the ngo tsha sprad rin.55