The Old Tibetan Chronicle

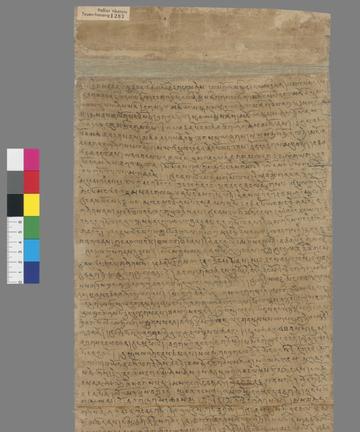

Pelliot tibétain 1287

Introduction

This historical document was found in the ‘library’ cave at Dunhuang. It contains a narrative, in a mixture of prose and verse, describing and praising the greatness and activities of Tibet’s rulers. It is concerned with the proper relationship between ruler and subjects, which are illustrated with examples of just and unjust conduct. The early emperors are said to have expanded their realms through superior moral qualities, as well as military prowess. As Kapstein and Dotson (2013) describe, it draws on eulogies to the kings found in official inscriptions and edicts, on narrative traditions from India and China, and on a poetic tradition of song and praise poetry.

The Chronicle (PT 1287) is thought to be linked to a related text (PT 1286), which contains a list of ancient polities and royal genealogies, ending with Langdarma (’U dum btsan, d.842). The Chronicle opens with Drigum Tsenpo (Gri gum btsan po), the seventh king. The reference to Langdarma suggests that these texts were composed after the 840s, while Beckwith and Walter (2015) argue that it must be a later compilation of earlier material, possibly made in the eleventh century.

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

Online transliterations:

PT 1286: http://otdo.aa-ken.jp/text/t/130

PT 1287: http://otdo.aa-ken.jp/text/t/131

References

Transliteration and translation:

Bacot, Jacques et al. 1940. Documents de Touen-Houang relatifs a l’Histoire du Tibet. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.

An introduction:

Kapstein, Matthew and Brandon Dotson. 2013. "The Old Tibetan Chronicles". In K. Schaeffer, M. Kapstein, and G. Tuttle (eds), Sources of Tibetan Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 36–46.

Other references:

Beckwith, Christopher I and Michael L. Walter. 2015. "Dating and Characterization of the Old Tibetan Annals and the Chronicle". In H. Havnevik and C. Ramble (eds), From Bhakti to Bon. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture.

Dotson, Brandon. 2007. "Divination and Law in the Tibetan Empire". In M. Kapstein and B. Dotson (eds), Contributions to the Cultural History of Early Tibet. Leiden: Brill.

––. 2009. The Old Tibetan Annals. Wien: Verlag der Österreichschen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Hahn, Michael. 1997. "A propos the term gtsug lag". In E. Steinkellner et al. (eds), Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Seventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, vol 1. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, pp.347–54.

Richardson, Hugh E. 1969. "Tibetan Chis and Tsis". Asia Major 14: 254–56.

Stein, R.A. 1985. "Tibetica Antiqua III: A propos du mot gcug-lag et de la religion indigéne". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient 74: 83–133.

Uray, Geza. 1968. "A Chronological Problem in the Old Tibetan Chronicle". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11: 268–69.

Outline

The transliteration and outline are based on the original texts and include the line numbers noted in the online transliterations. The page references are to the earlier transliteration in Bacot et al (1940). There is considerable uncertainty over the correct translation of several parts of the text. The version offered here has made use of those found in Bacot et al. (1940), Dotson (2007), and Kapstein and Dotson (2013).

PT 1286

The text contains a list of ancient polities and royal genealogies, ending with Langdarma (’U’i dum brtan).

- Lists of kings, their families, and ministers

- Accounts of the kingdom under Tri Nyatri Tsenpo (Khri nyag khri btsan po)

- Lists of kings, their families, and ministers up to Langdarma

PT 1287

This text is a military and political history of the kings of Tibet. It starts with King Drigum (Gri gum), seventh Tibetan king, continuing up to King Tri Song Detsen (Khri srong lde brtsan), late eighth century. The chronology is not entirely straightforward. In particular, events recounted in section eight, including the establishment of law and administration, are supposed to take place under Tri Song Detsen, but later in the same section are attributed to the earlier ruler, Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po).

- Drigum, seventh king of Tibet and his sons and their reconquest of Tibet.

- King Detru Namzhung (lDe phru bo gnam gzhung), the sixteenth king and the ministers under him, subsequent kings, up to and including Songtsen Gampo.

- Activities of and power struggles between ministers under forbears of Songtsen Gampo.

- Regional relations and intrigues during the reign of Tri Lontsen (Khri slon brtsan), father of Songtsen Gampo.

- Relations of loyalty and protection between Songtsen Gampo and one of his ministers.

- Conquests and intrigues among Songtsen Gampo’s ministers.

- Conquests of Tri Dusong (Khri ’dus srong).

- Reign of Tri Song Detsen, establishment of Buddhism, and conquest of the Tibetan empire.

- Song of Tri Dusong and response of the ministers.

- Skirmishes between Chinese and Tibetan generals.

Extracts

PT 1287 (Section 5)

The dbyi tshab of dBa’ has become an old man and the king promises to erect a tomb for him, in recognition of his fidelity. The king and his six ministers swear an oath: ‘If you, father and sons, remain faithful to the king of Spu:

[PT1287, Section 5, p. 110, l. 8]

(279) … དབྱི་ཚབ་གྱི་བུ་ལ་

(280) མ་ཉེས་པར་བཀྱོན་དབབ་རེ། འཕྲའ་མ་མྱི་ངག་གསན་རེ། འཕྲའ་མ་ཞིག་གསན་ན་ཡང། ཤགས་བྱ་སྟེ་

(281) ཡུས་བཀྲོལ་ནས། །བཀའས་མྱི་གཆད་( གཅད་) རེ།

We will not accuse the innocent sons of the dbyi tshab; we will not listen to those who make false accusations. If we do hear a false accusation, it ought to be rejected (shags bya); after the claims are disentangled, we will not pronounce a judgment.

PT 1287 (Section 8)

[PT1287, Section 8, p. 114]

(366) … ༅། །བཙན་པོ་ཁྲི་སྲོང་ལྡེ་བརྩན་གྱི་རིང་ལ། །ཆོས་བཟང་སྲིད་ཆེ་སྟེ། རྒྱལ་པོ་ནི་གནམ་ས་གཉིས་ཀྱི་བར་ཡུལ་དུ་

(367) བརྣམ་ཞིང་། །འགྲེང་དུད་གཉིས་ཀྱི་རྗེ་དང་བདག་མཛད་པའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཆེན་པོ། མྱིའི་དཔེར་རུང་བར་མཛད་དོའ། །

(368) ལེགས་ཀྱི་བྱ་དགའ་ནི་རངས་པར་བྱིན། ཉེས་ཀྱི་ཆད་པ་ནི་དམྱིགས་སུ་ཕོག་པར་མཛད་དོ། །འཛངས་པ་དང་དཔའ་

(369) བོའི་རི་མོ་བསྐྱེད་དོ། །ངན་པ་མ་རབས་ནི་ཆིས་ཀྱིས་གསོས་སོའ། །དེའི་ཚེ་བློན་པོ་སྲིད་བྱེད་པའི་རྣམས་ཀྱང་།

(370) བློ་མཐུན་གྲོས་གཆིག་སྟེ། །པྱིའི་དགྲའ་བྱུང་བ་ལ། ཐབས་དང་ཡེ་མྱིག་ཆེར་བྱེད། ནང་གི་ཆོས་བྱ་བ་ལ་དྲང་ཞིང་འགྲུས་

(371) སུ་བྱེད།

During the reign of Tri Song Detsen, the customs were excellent and the realm extensive (chos bzang srid che), and the king maintained it between sky and earth. The great order (gtsug lag chen po), by which he obtained sovereignty over both men and beasts, served as a model for men. Rewards for good deeds were given with pleasure, punishment for bad deeds was given with discernment. Wisdom and courage increased. The administration (chis) supported the common people. At that time, the governing ministers agreed and acted unanimously. If a foreign enemy appeared, they augmented their resources, and as regards internal practices (chos), they acted correctly and diligently.

Shortly afterwards there is a reference to the introduction of Buddhist doctrine (sangs rgyas kyi chos).

Later, the section returns to the activities of Songtsen Gampo.

[PT1287, Section 8, p. 118, line 6]

(446) བླ་ན་རྗེ་སྒམ་ན། ཁྲི་སྲོང་བརྩན། འོག་ན་བློན་འཛངས་ན་སྟོང་རྩན་ཡུལ་ཟུང་།

(447) རྗེ་ནི་གནམ་རི་ཕྱྭིབ་ལུགས། །བློན་པོ་ནི་སའི་ངམ་ལེན་གྱི་ཚུལ། །མངའ་ཐང་ཆེན་པོའི་རྐྱེན་དུ། ཇི་དང་ཇིར་ལྡན་ཏེ། པྱིའི་

(448) ཆབ་སྲིད་ནི་པྱོགས་བཞིར་བསྐྱེད། །ནང་གི་ཁ་བསོ་ནི་མྱི་ཉམས་པར་ལྷུན་སྟུག །འབངས་མགོ་ནག་པོ་ཡང་མཐོ་དམན་ནི་

(449) བསྙམས། དཔྱའ་སྒྱུ་ནི་བསྐྱུངས། དལ་དུ་ནི་མཆིས། སྟོན་དཔྱིད་ནི་བསྐྱལ། །འཁོར་བར་ནི་སྤྱད། འདོད་པ་ནི་བྱིན།

(450) གནོད་པ་ནི་པྱེ། བཙན་བ་ནི་བཅུགས། སྡོ་བ་ནི་སྨད། འཇིགས་པ་ནི་མནན། །བདེན་བ་ནི་བསྙེན། འཛངས་པ་ནི་བསྟོད།

(451) དཔའ་བོ་ནི་བཀུར། སྨོན་པར་ནི་བཀོལ། །ཆོས་བཟང་སྲིད་མཐོ་སྟེ། །མྱི་ཡོངས་ཀྱིས་སྐྱིད་དོ།

Above, if a lord was profound, it was Tri Song Detsen; below, if a minister was wise, it was sTong rtsan yul zung. The lord, in the tradition of the sky and mountain Phywib [Phywa] deities, and the ministers, in the manner of earthly conventions, possessed each and every attribute of authority. Externally, they expanded the kingdom in all four directions; internally, welfare was abundant and undiminished. As for the black-headed subjects, high and low were levelled, unjust taxes were avoided, people went about in peace, spring followed autumn. The court travelled around the realm, they gave to the needy, they segregated the harmful, they controlled the powerful, they reduced hazards, they mastered the dangers, they allied with the truthful, they revered the wise, they honoured the heroic, and they made appointments with inspiration. The customs were excellent (chos bzang), the realm was civilized (srid mtho), and everyone was happy.

(451) … བོད་ལ་སྔ་ན་ཡི་གེ་

(452) མྱེད་པ་ཡང་། །བཙན་པོ་འདིའི་ཚེ་བྱུང་ནས། །བོད་ཀྱི་གཙུག་ལག་བཀའ་གྲིམས་ཆེད་པོ་དང། བློན་པོའི་རིམ་པ་དང། ཆེ་ཆུང་

(453) གཉིས་ཀྱི་དབང་ཐང་དང། ལེགས་པ་ཟིན་པའི་བྱ་དགའ་དང། ཉེ་ཡོ་བའི་ཆད་པ་དང། ཞིང་འབྲོག་གི་ཐུལ་ཀ་དང་དོར་ཀ་དང། སླུངས་ཀྱི་གོ་བར་བསྙམས་

(454) པ་དང། བྲེ་པུལ་དང། སྲང་ལ་ལྕོགས་པ། །བོད་ཀྱི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་གཞུང་བཟང་པོ་ཀུན། །བཙན་པོ་ཁྲི་སྲོང་བརྩན་གྱི་རིང་ལས་བྱུང་ངོ་། མྱི་ཡོངས་

(455) ཀྱིས་བཀའ་དྲིན་དྲན་ཞིང་ཚོར་བས། །སྲོང་བརྩན་སྒམ་པོ་ཞེས་མཚན་གསོལ་ཏོ། །

Formerly there was no writing in Tibet. The emperor of that time made a great code for the Tibetan order (gtsug lag) and a hierarchy of ranks for the ministers, with divisions into great and small. He established rewards for good deeds, punishments for bad deeds, even division of fields and pastures into thul ka, dor ka, and slungs, standardized weights and measures into bre, phul, and srang, and so on. All the excellent established customs of Tibet (bod kyi chos kyi gzhung bzang po) were created during the reign of Khri srong brtsan, for which all people were grateful. This is why he was called Songtsen Gampo.