The Testament of Tai Situ Jangchub Gyaltsen

Ta si tu Byang chub rgyal mtshan gyi bka' chems mthong ba don ldan

Introduction

The seat of the Lang Pakmodru (Rlangs phag mo ʼgru) was established at Densatil (Gdan sa mthil) in central Tibet in the twelfth century. Initially closely associated with the Drigung Kagyu (’Bri gung bka’ brgyud) they developed a distinct religious sect (Phag mo bka’ brgyud). In the 1240s, the Pakmodru domains were recognized as one of the thirteen trikor (khri skor) within the Yuan administrative structures, with the seat of its leader, the tripon (ikhri dpon), at Neudong (Sne’u gdong) in the Yarlung valley.

In 1322 Jangchub Gyaltsen (Byang chub rgyal mtshan, 1302–1364) was appointed as leader by the Yuan emperor and he gradually wrested power from the formerly powerful Sakya (Sa skya) and their ponchen (dpon chen) in central Tibet. This was recognized by the Yuan when the emperor granted him the title of Ta’i Situ in 1357 and he received the ponchen’s seal of office. Jangchub Gyaltsen created new administrative offices, gradually coming to exercise authority over the other tripon. He reorganized the trikor into the fort (dzong) system, with associated aristocratic families and estates.

The Testament was probably completed shortly before his death in 1364.

Download this resource as a PDF:

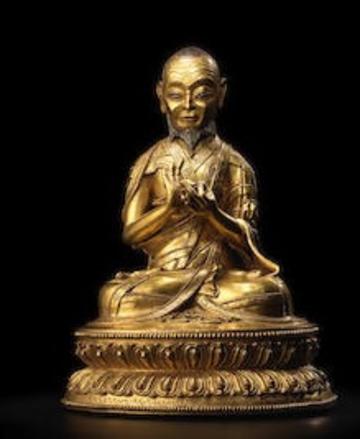

© Bonhams

Sources and references

Byang chub rgyal mtshan. 1974. bKa’ chems mthong ba don ldan. In Lha rigs rlangs kyi rnam thar. A detailed account of the Rland lineage of Phag-mo-gru-pa rulers of Tibet. New Delhi, pp. 217–836.

Byang chub rgyal mtshan. 1986. bKa’ chems mthong ba don ldan. In Rlangs kyi po ti bse ru rgyas pas, Chab spel Tshe brtan phun tshog (ed.) Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, pp. 103–373. BDRC: W18579

Byang chub rgyal mtshan. 1989. bKa’ chems mthong ba don ldan. In Ta si byang chub rgyal mtshan gyi bka’ chems mthong ba don ldan bzhugs so. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, pp. 1–282.

Ta si Byang chub rgyal mtshan. 2013. Ta si Byang chub rgyal mtshan gyi bka' chems mthong ba don ldan. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang.

Czaja, Olaf. 2013. Medieval Rule in Tibet: The Rlang Clan and the Political and Religious History of the Ruling House of Phag mo gru pa. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

van der Kuijp, Leonard W. J. 1991. “On the Life and Political Career of Ta’i-si-tu Byang-chub rgyal-mtshan (1302–?1364).” In Tibetan History and Language: Studies Dedicated to Uray Géza on his Seventieth Birthday, edited by Ernst Steinkellner, 277–327. Wien: Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien.

—. 1994a. “Fourteenth Century Tibetan Cultural History 1: Ta’i-si-tu Byang-chub rgyal-mtshan as a Man of Religion.” Indo-Iranian Journal 37 (2): 139–149.

—. 2010. “The Tibetan Expression ‘bod wooden door’ (bod shing sgo) and Its Probable Mongol Antecedents.” In Historical and Philological Studies of China’s Western Regions, edited by Weirong Shen, 89–134. China: Science Press.

Extracts

The page numbers are references to the 1986 edition.

1240

Chenga rinpoche (Spyan snga rin po che) is at the court of the Pakmodru (the ’jig rten mgon po chos rje) at Densatil. During the reign of Ogodai (O ko ta), son of Chengis khan (Jing gir), the Hor general, Dorta Nakpo (Dor ta nag po), arrives in Tibet.

[p. 109]

ཁུ་དབོན་གཉིས་ཀྱི་རིང་ལ་བོད་དུ། ཧོར་ཁྲིམས་བྱུང་འདུག ཧོར་དོར་ཏ་ནག་པོས་དམག་དཔོན་བྱས་ནས།

During the time of the two, the uncle and nephew,1 the law of the Hor came to Tibet. The Hor general was Dor ta nag po.

The general captures the Drigung (’Bri gung) gom pa (sgom pa, civil administrator), Shakya rin chen, only to be met by earthquakes and hail stones. He then venerates Chenga rinpoche and establishes fortresses.

ཁྲིམས་འཇགས་སུ་བཅུག་ནས། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས། ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་ནམ་ལངས་པ་ལ་ཉི་མ་ཤར་བ་ལྟ་བུ། བོད་སྐད་རིགས་གཅིག་པའི་ཁུལ་འདིར་བྱུང་འདུག་པ། སྤྱན་སྔ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་བོད་ཁམས་ཙམ་ལ་བཀའ་དྲིན་ཆེ་བའི་དོན་དེ་ཡིན།

When he had established the law, the royal and religious law were like the rising sun at daybreak and a domain with a single Tibetan language emerged. This was thanks to the great kindness of Spyan snga rin po che.

1290s

The text discusses the activities of various rulers, including the tripons, and the receipt of an order (’ja’ sa) from the emperor. Regarding the tripon Zhonu Yontan (gZhon nu yon tan):

[p. 119]

མི་སྡེའི་ས་རིས་གན་མེ་ཏོག་གི་ཕྱོགས་དང་། ཁྲལ་ཆུ་རྣམས་ལ། ས་སྐྱ་པའི་ཕྱག་ཏུ་ཤོར་བ་ཐམས་ཅད། ཞི་བར་གཤེགས་པའི་ཕྱག་རྫས་སྟེང་ནས་བླུས། མི་སྡེའི་དུད་དང་། བཅུ་རེང༼འབྲང༽་བཅུ་སྐོར་སྡེབས་ཤིང་། གཞན་འཇམས་མེ་ཏོག་ལ་སོགས་ཁྲིམས་ཁྲལ་སྒྲུབ་དགོས་རྣམས་འགྲུབ་ཙམ་འདི་ཞི་བར་གཤེགས་པའི་སྐུ་དྲིན་དུ་འདུག

Regarding the water taxes of the area of Sa ris gan me tog, all was lost to the hands of the Sa skya pa, [but] they were recovered from the possessions [of the Sa skya] at his death.2 He combined the households of the area (mi sde) into an arrangement of ten by ten dwellings [but] the [steps] necessary to establish postal stations at such places as Me tog and to enact tax regulations were only taken after the kindness of his passing.3

1346

There is a long-running dispute between Jangchub Gyaltsen (Byang chub rgyal mtshan), who was then tripon and contending with the Sakya, among others, for ultimate power in central Tibet, and the Gya zangpa (G.ya bzang pa). The latter gather troops from the G.ye, Gnyel, and Ngo log.

[p. 167]

མེ་ཕོ་ཁྱི་ལོ་ཟླ་བ་བརྒྱད་པའི་ཚེས་བརྒྱད་ལ། གཡེ་བསྙལ་གྱི་དམག་རྣམས་ཚུར་སླེབ། བཅུ་གཅིག་གི་ཉིན། རྡོག་པོ་རྒྱུད་ཀྱི་གསེབ་ལ་ལག་ཐུག་འདུག་པ་ལ། ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་བདེན་ཆ་ཡོད་པ་དང་། དཀོན་ཅོག་མཁའ་འགྲོས་དཀར་ནག་ཤན་ཕྱེ་ནས། རང་རེ་བྱུས་ལེགས། མ་དགའ་དགྲ་དགས་འགོ་བྱས་མི་ཉི་ཤུ་ཙམ་བསད་འདུག་ནའང་། རྒྱལ་ཚོད་བཟུང་ནས་འདེད་ཐག་ཐུངས།

On the eighth day of the eighth month of the male fire dog year, the army of G.ye bsnyal arrived. On the eleventh day, they [came to] the gSeb la pass on the rDog po range. They were acting lawlessly (khrims kyi dben cha yod pa). The Three Jewels and female deities distinguished good and bad. Our strategies were good. We killed their leader, Ma dga’ dgra dga, and about twenty men and when we were victorious, we pursued them a long way.

Then the ponchen Gyalba zangpo (rGyal ba bzang po) intervenes and challenges (or arrests) Jangchub Gyaltsen. The latter addresses the ponchen.

[p. 171]

ང་རང་དངོས་ཀྱིས། དཔོན་ཆེན་པའི་དྲུང་དུ། ཡང་ཡང་ཞུས་པ་ལ། ད་དྲུང་ནས་ཐུགས་མ་འཁྲུལ་བ་མཛད་པར་ཞུ། ས་སྐྱ་པའི་བླ་མ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་མཛད་སྤྱོད་འདིར་སོང་། དཔོན་ཆེན་གྱི་ནོན་མ་བྱུང་ན། ཁྲིམས་མི་ཡོང་བར་འདུག་པས། ངས་ཁྱེད་ཀྱི་དབུ་འདོན་དུ་འགྲོ་བ་བྱེད ཨན་ཟླ་བ་ཕྱེད་འཁུར། ཕུགས། འཇའ་ས་ཡིག་རིགས་ཀྱི་སྟེང་ནས། བདེན་ཐོག་ཏུ་གཏོང་བར་ཞུ་ཞུས་

I, myself, repeatedly request the dpon chen to act graciously now, without error. The practices of the Sa skya lamas have arrived here. When the dpon chen was not in control, there was no law. I beseech you: I have been wearing shackles (An) for half a month; may I finally be released in accordance with the truth of the ʼja’ sa documents?

There is then conflict between the Pagmodru and the ponchen Wangtson (Dbang brtson), whose allies are the Tselpa (Tshal pa) and the Gya zangpo.

In 1349 Jangchub Gyaltsen attacks the Gya zangpa and in 1350 he seizes Gongkar (Gong dkar). A mediation is initiated at Rabtsun (Rab btsun), but then the ponchen attacks Gongkar. Jangchub Gyaltsen goes to Tsel Gungtang (Tshal Gung Thang) and forces the Tselpa to surrender and hand over a son as hostage. Then he goes to Gyama (rGya ma), where he meets the Drigung administrator (gompa, sgom pa) Kunga Rinchen (Kun dga’ rin chen), who is now being supported by the Yuan. Jangchub Gyaltsen explains that he is weary of the fighting and the attacks on his property and wants to pursue a mediation and seeks to persuade the gompa to do the same, on the basis that he will no longer fear the imperial army (khrims dmag). The gompa retorts, sceptically:

[p. 203–04]

ཧོར་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཏིག་ཏིག་ཨེ་ཡོད་ཟེར། ཧོར་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཏིག་ཏིག་མེད་ན། ཁྱོད་འདན་མ་དང་། ང་གནས་དྲུག་པ་གཉིས་ལ་ཅི་དོན། ཧོར་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཏིག་ཏིག་ཡོད་པ་ཨེ་མ་དགའ། མོན་འགོར་རྒྱལ་པོའི་དྲིན་དང་ཁྲིམས་ལ། ཁྱེད་འབྲི་ཁུང་པའི་མིང་དང་བསྟན་པ་བྱུང་བ་ཡིན། སེ་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་དྲིན་དང་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ས་སྐྱ་པ་དང་། ཚལ་པའི་མངའ་ཐང་བསྟན་པ་བྱུང་འདུག། ཧུ་ལ་ཧུ་ཡི་དྲིན་ལ། ཕག་མོ་གྲུ་པའི་སྡེ་དང་ཚུགས་བྱུང་འདུག་བྱས་པས། ཕ་ཏ་ཚུ་ཏ་དགའ་བ་ཡིན་ཟེར་ནས་མགོ་སྤྲུག་གི་འདུག་ང་ངོ་མ་ལོག་པར་ལོག་ཟེར་ནས། གོང་དུ་རྫུན་ཡིག་མང་པོ་སོང་ཡོད་པར་འདུག་པས། གོང་ནས་བདེན་བརྫུན་བལྟ་མི་བྱུང་ན། འདམ་སྟག་ལུང་ཚུར་བཅད་ཀྱི་མི་སྡེ་འདི། ཁྲིམས་བསྡམས་སྐྱིད་དུ་བཅུག་ནས། ང་རྒྱལ་པོ་ལ་ངོ་ལྟ་བའི་ཕྱག་རྟེན་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན།

‘What are the advantages (tig tig) of Hor laws?’ [Byang chub rgyal mtshan] replies, ‘What would be the benefit for either your seat or my six areas if there were no advantages to the Hor laws? The Hor laws are extremely advantageous. Due to the benefaction and the laws of the Mon ʼgor king,4 you ʼBri gung pa have acquired your name and your teachings; due to the benefaction and the laws of Sechen,5 the Sa skya pa and the Tshal pa acquired their power and their teachings; due to the benefaction of the Hulegu,6 the territory of the Phag mo gru has been established.’

He then complains about the letters in which the gompa has been deceitful, and then claims that he, himself, has made the area around Taglung (sTag lung) happy by establishing the law there (khrims bsdams skyid du bcug nas).

In 1354 a meeting takes place at Gongkar, between Lama Dampa (bLa ma dam pa), the ponchen Gyalba Zangpo, and Jangchub Gyaltsen. The first two accept the power of Jangchub Gyaltsen and that Gongkar will remain in his possession. Then Lama Dampa and the ponchen returned to Kyisho (sKyid shod).

The Tselpa lay seige to Dronpari (Gron pa ri) and ask for help from the Pagmodru, who send the chenpo Rinzang (Rin bzang), who is victorious. But then the Nangpa Kunga Bum (Kun dga’ ʼbum) arrives with new troops. The Nangpa Drakwang (Grags dbang) attacks Tongmon (mThong smon) in Shangs, the stronghold of the Ponchen. The latter then calls on Jangchub Gyaltsen for assistance.

[p. 237]

དཔོན་ཆེན་པ་ཡང་ཐུགས་ཐོར༼འཁྱར༽་ནས་འདི་བྱ་མ་བྱུང་བའི་སྐབས་སུ། རང་རེའི་ཆེན་པོ་བས་དབུ་མཛད་དམག་དཔོན་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། ད་འདི་ལ་ཇི་ལྟར་བྱ་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་ཟེར་བ་ཞུས་འདུག་པས། ཤངས་པའི་ཁ་མཚུལ་ནི་འདིར་སོང་། ཁྱེད་ཚང་གིས་ཁྲིམས་གྲོགས་བྱས་ན། ངེད་ཀྱིའང་སྙིང་གིས་ནུས། རང་རེས་གྲོགས་མ་བྱས་ན་མི་ནུས་གསུངས་འདུག དེ་ནས་རང་རེ་ལ་དམག་དཔོན་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་ཞུ་བ་བྱུང་ནས། དཔོན་ཆེན་པ་འདི་གསུང་། ད་ཇི་ལྟར་བྱེད་ཞལ་ཏ་ཞུ་ཟེར་བ་བྱུང་། ཁྲིམས་གྲོགས་བྱེད་པ་ལས་འོས་མེད་པས། དེར་ཞུས་པ་ལ་ཐག་ཆོད་ཟེར་བ་བསྐུར། དེ་རྟིང་། ཆེན་པོ་བས་དབུ་མཛད་ཕྱིར་ཡང་ལུངས༼ཀླུངས༽་སུ་སླེབས་པ་དང་། ནང་པ་འདེད་པ་དང་ཁྲིམས་གྲོགས་ལ། ཆེན་པོ་བས་དབུ་མཛད། འགྲོ་དགོས་བྱས་ནས་དམག་བཅས། དམག་བཏེག་ནས

Then, after the dpon chen again changed his mind (lost his nerve?) and did not do this, the army generals appointed as leaders by our chen po asked: ‘Now what should we do? A message from Shangs has arrived here, saying “If you give assistance in the law, I/we will be able to act whole-heartedly (courageously). If we do not help each other, this will not be possible’. Then a request by the generals came to us, saying: ‘The dpon chen has spoken, what is your advice now? Since there is nothing more appropriate than giving assistance in [imposing] law, we ask you to make a decision on the request’. Subsequently, the those appointed by the chen po arrived back at Yang lungs (or the cultivated area) and in order to rout the nang pa and help [impose] law, those appointed by the chen po were told to go and (they) set off with his army.

Still in 1354, after further manoeuvring, including tussles over the possession of the most important seals, Jangchub Gyaltsen has a meeting at Chumig with two representatives of the Sakya counsellors. He tells them that they must immediately release the ponchen.

He criticizes their seizure of the ponchen in the following terms:

[p.257]

བསྙེན་བཀུར་འདྲེན་དུ་ཡོང་བ་མིན། ཁྱེད་ས་སྐྱ་པའི་བླ་མ་ཚོ་ཡང་། ངས་ཕྱག་འཚལ་བ་མ་རེ། བླ་མའི་བུ་གཉིས་པོ་ཟིན་ན་འཛིན། ལག་ཏུ་ཆུར་ན་གསོད། དཔོན་ཆེན་འདོན་པ་དང་ཁྲིམས་གྲོགས་ལ་ཡོང་བ་ཡིན། གེབ་ཅག་ཏའི་ཕིང་ཇང་དང་། དར་མ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་སི་ཏུས་གདན་དྲངས་པའི་འཇའ་སའི་ནང་ན། ཁྲིམས་དང་འགལ་བ་བྱེད་པའི་གྱོང་པོ། ངོ་ལོག་རྣམས་རྡེག་གིན་འཆོས། གསོད་ཀྱིན་འཆོས་ལ། རྟིང་ལ། ངེད་ལ་ཞུ་བ་ཐོངས་གསུང་བ་ཡོད། དེའི་ཞལ་བཤུས་ཀྱང་། རང་རེ་ཐམས་ཅད་ལ་ཡོད་པ་ཡིན། དེའི་ལུགས་བཞིན། ངོ་ལོག་གྱོང་པོ་རྣམས་བསོད་གིན་རྡེག་གིན་བཅོ། རྟིང་ལ། གོང་དུ། ཞུ་བ་གཏོང་

I did not invite veneration (bsnyen bkur). However, you Sa skya lamas should not hope that I make prostrations. If both sons of the lamas have been captured, hold on to them. If they fall into my hands, I will kill them. I have come to release the dpon chen and to give legal assistance (khrims grogs). In the ’ja’ sa brought by the phing jang Geb cag ta’i and the Si tu Dar ma rgyal mtshan, it is said that dangerous rebels who break the law (khrims ’gal ba) should be beaten; they should be killed; and later a report should be sent to me (the emperor). We all have a copy of that order (zhal bshus). Accordingly, the rebels should be killed and beaten and afterwards a report should be sent to the emperor.

p. 259: The phrase khrims med byas is used to refer to people behaving badly, literally lawlessly. In this case it is the nephews of the ponchen, who have carried out raids.

Later, there are further negotiations about the release of the ponchen Gyalba zangpo. The lama Kunspangpa (Kun spangs pa) suggests that his son, the lopon (slob dpon) Grakpa Gyaltsen (Grags pa rgyal mtshan), should be sent in exchange. Jangchun Gyaltsen consults the Shangspa councillors, under the lopon and sends a message to Lama Kuspangpa, asking him to hand over the ponchen, saying:

[p. 261]

དེའི་ཁག་འཁུར་བའི་ཕྱག་རྟགས་ཞུ། ཁྲིམས་དཔང་པོར་བཞག་པའི་ཞབས་ཏོག་ཏུ་གང་འགྲོ་བྱེད།

I ask for a hand-imprinted document about taking responsibility for him, which will establish the lawfulness [of what I am doing] wherever I go.

Later, the ponchen is released and a meeting takes place to discuss the lama Khangsarba (Khang gsar ba). The ponchen makes a speech:

[p. 283]

བླ་མ་ཁང་གསར་བ་བྱ་བ་མ་ལགས། བྱི་ཕོ་གཉའ་སྒུར་བ་བྱ་བ་ལགས། ཇག་པ་བདེ་ལེགས་རྒྱལ་མཚན་བྱ་བ་ལགས། བླ་མའི་དོན་ཅི་བདོག འཁང་འདྲ། ཁམས་པ། ཇག་པ་ངོ་ལོག་ཚོ་ལ། ཆོང༼ཚོང༽་རྩེ་བྱུང་བ། པང་པ་གང་ཙམ། འམ་བུའི་ལག་ན་བདོག འདི་ལ་རྒྱལ་བུ། དབེན་པ། མང་དུ་འཚོགས་ནས། བཅའ་རྩེ་བླངས། ཕྱུག་པོ་སྒོ་དམར་བ་ལ། གོང་དུ་ཞུ་བ་སོང་བདོག འདི་ལ་ཙ་ར་ཡོང་ན་ཕྱུག་པོ་སྒོ་དམར་བ་ལ་ཡོང་འཆི༼མཆི༽་འདྲི་མི་དང་། རྩད་དཔྱོད་ཡོང་ན། གོང་ནས་ཡོང་མཆི། ང་རྒྱལ་བ་བཟང་པོ་ས་ལ་མི་འཛུལ། གནམ་ལ་མི་འཕུར་མི་འབྲོས་ལགས། འམ་བུས་མཐེབ་བོང་ཙམ་ཞིག་ནས། གོང་མའི་གསེར་གྱི་ཐེམ་པ་བརྫིས། གོང་མའི་གསེར་ཞལ་མཐོང་། ཕིང་གཅིག་པའི་ཁྲིམས་སར༼རར༽་སླེབས། ལག་རྟགས་བརྒྱབ། ཁྲིམས་འདི་འམ་བུས་ཤེས་ལགས། འདི་ན། ཁྱེད་རྣམ་པ་མི་དབང་ཅན་མང་ནས། ཁྲིམས་འགྲིམས་མི་གདའ་བ་གསུངས།

He is not known as bla ma Khang gsar. He is known as a hunchback womaniser. He is known as the bandit bDe legs rgyal mtshan. What is the worth of [this] bla ma? He is like someone with a grudge. He primarily profits the Khams pa, brigands, and rebels. I have a lap full [of incriminating evidence] in my hands. When the prince, the dben pa, and many others gathered here, they took up an official documents (bca’ rtse), which was sent as a request to the emperor, in the imperial capital (lit. the rich one with the red door). In that regard, if punishment is ordered, it will be at the imperial capital; if interrogators and investigators come, they will come from the emperor.

I, rGyal ba bzang po, I do not creep on the ground, I do not fly up to the sky, I do not flee. I pressed one thumb on the golden threshold of the emperor, I saw his golden countenance. When I arrived at the court (khrims sa) of those of the first rank (phing gcig), I made my hand mark. I know this law (khrims). Here, where there are many powerful men, such as you, the law cannot wander (khrims ʼgrims mi gda’ ba).7

Jangchub Gyaltsen replies, saying that no-one doubts that he knows the law.

[p. 283–84]

ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཁོག་ཚུད་མཛད་ཀྱི་གདའ་བ། བཀའ་གདམས་པའི་ཁོག་ཚུད་ཡིན་ན། ཤ་དང་མར་ཚུད་ཆེན་པོ་ཡོང་བས། ཟ་ཆེ་བ་ཡིན་ཏེ། རང་རེའི་ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཁོག་ཚུད་འདི་མི་འཐད་

Acting in accordance with (lit. inside) the law (khrims la khog tshud) means acting in accordance with (lit. going inside) instructions; [but] to go completely inside meat and butter, is to over-eat. [Therefore], to act in accordance with each law is not feasible.8

He continues by talking about the time he was imprisoned by the ponchen, and the incident when he burnt his seal. He mentions the time when Salé fort (gSal le rdzong) was overthrown. Then:

[p. 285]

ཞང་མཁན་པོས་འགོ་བྱས་རྣམས་བསད་ཡོད་པས། སི་ཏུ་དར་མ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ལ་གནང་སྦྱིན་དང་། ལས་ཀ་སྤོར་བ། དཔོན་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་བཟང་གིས་ཀྱང་གོང་མའི་ཕྱོགས་སུ་བསམས་ནས་དམག་ལེགས་པར་འཐབ་ཡོད་པས། གནང་སྦྱིན་དང་ལས་ཀ་སྤོར་བ་ཞུ་ཟེར་བའི་༼སྙན་ཞུ༽་བཏང་ནས། འཇའ་སའི་ལུགས་བཞིན་ངོ་ལྟ་བྱས་པའི་མི་བསད་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ལུང་ལོག་པར་བཏང་ངམ་མ་བཏང་། ཁྲིམས་ལ་ཁོག་ཚུད་བྱས་སམ་མ་བྱས།

The Zhang mkhan po and his leaders were killed. Si tu Dar ma rgyal mtshan was given gifts and his work was elevated (he was promoted). The dpon chen rGyal bzang requested that because he had fought well according to the wishes of the emperor, he should also receive gifts and be promoted. Since he killed someone on the basis of the ʼja’ sa, [the question is], was the king’s instruction sent correctly or not and did he act in accordance with the law (khrims la khog tshud), or not?

Jangchub Gyaltsen continues by saying:

ང་སྣེ་གདོང་གོང་དཀར་ནས། རྒྱལ་རྒྱུད་མི་དཔོན།་གསེར་ཡིག་པ་སུ་བྱུང་ཡང་། བསུ་བ་ལ་ཐག་རིང་པོར་མི་འགྲོ་བར། ཐེམ་པ་ལ་རྡོག་པ་གཏོད་པའི་དོན་དེ་ཡིན། ངས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཁྲིམས་བཟུང་། གན་མེ་ཏོག་གིས་འགོ༼མགོ༽་བྱས། སྡུད་ཆེ་ཆུང་། ཁྲིམས་ལས་ཀྱི་བྱ་བ་དྲང་པོར་བསྒྲུབས་པའི་མི་དཀར་པོ་ལ། ཞབ༼ཞྭ༽་ནག་པོ་གཡོགས་སམ་མ་གཡོག གོང་དུ་ངོ་ལོག་ཟེར་བའི་ཞུ་བ་བཏང་ངམ་མ་བཏང་།

When I was at sNe gdong Gong dkar, whenever royalty or dignatories or emmissaries came, I offered them lengthy hospitality. My purpose was to make them welcome. I abide by the king’s law (rgyal po’i khrims bzung). I have been appointed by Gan Me tog. Does a person with a black hat serve a white person, who is accomplished in acting in accordance with the law (khrims las kyi bya ba drang por bsgrubs pa)? Have I spoken in a rebellious way about the king or not?

He then gives an example of improper behaviour, namely, the killing of a disabled person.

Early in 1357, Jangchub Gyaltsen receives an imperial mission, which brings a decree that the title and seal of Ta’i Si Tu are to be bestowed upon him.

Conflict between the Pakmodru and the Drigung is inevitable and Jangchub Gyaltsen explains the situation. The Drigung have already made threatening statements about seizing his territories and annihilating his lineage. If he hands over Olkha (ʼOl kha), then rebels from Ye (g.Ye) and Nyel (gNyal) will side with the Drigung and the Sakyapa would order him to interfere.

[p. 290]

འོལ་ཁ་གཏད་ན། འབྲི་ཁུང་པ་དང་། གཡེ་གཉལ་ལ་སོགས་ངོ་ལོག་དང་གཅིག་བྱས་ནས་རང་རེ་ས་སྐྱ་པས་ཁ་ཆུག་པ་དང་། རྒྱལ་པོའི་ཁྲིམས་འཁུར་བ་མི་སྲིད་པས། འདི་མི་གཏོད་པའི་དོན་དེ་ཡིན།

If ʼOl kha is handed over, then rebels from g.Ye and gNyal will join with the ʼBri khung. The Sa skya pa will order me [to interfere] and I will not be able to abide by the king’s law (rgyal khrims). That is the reason I will not hand it over.

In the final section, Jangchub Gyaltsen talks about times of official extortion (za ʼdod) and how it is important to have strict laws (khrims dam), in order to avoid this:

[p. 372]

རྒྱའི་ཡུལ་དུ་ཁྲིམས་མ་འཇགས་པའང་། གསེར་ཡིག་པ་དང་མངག་གཞུག་པ་ཚོའི་ཟ་འདོད་ཀྱིས་ལན། སྔོན་འབྲི་ཁུང་པའི་བསྟན་པ། སྒོམ་པ་ཤཀ་རིན་གྱི་དུས་སུ་དར་ནའང་། དུས་ཕྱིས་བསྟན་པ་ཉམས་པ་དེ། ཟ་འདོད་དང་ཁྲིམས་མེད་མང་པོ་དེས་ལན་པ་ཡིན།

In the royal territory, law was not established (khrims ma ʼjags pa) and the response of the imperial officials and emissaries (gser yig pa dang mngag gzhug pa) was extortion. Formerly, during the time of the gompa Shakya rinchen, the teachings of the ʼBri khung pa spread, but later the teachings degenerated and much extortion and lawlessness resulted.

Footnotes:

- This most likely denotes Chennga Drakpa Jungné and his nephew and abbatial successor at Densatil Gyalwa Drakpa Tsondrü (Rgyal ba rin po che Grags pa brtson ’grus, 1203–1267). ↩

- This appears to be a reference to Sakya Drakpa Rinchen (Grags pa rin chen), who died in 1310. ↩

- This seems to be a sarcastic reference to the shortcomings of this official. ↩

- The khan Mongke, d. 1259 ↩

- The khan Qubilai, d. 1294. ↩

- The khan Hulegu, d. 1265. ↩

- Czaja offers a slightly different translation at (2013: 162, fn. 160) ↩

- The exact translation and meaning of this proverb is not certain. ↩