The Scripture from the Sky

gNam babs kyi dar ma bam po gcig go

Introduction

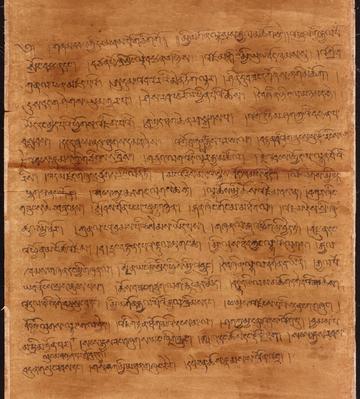

This manuscript was found in the ‘library cave’ at Dunhuang. It appears to contain the first part of a longer text, and Richardson (1977) suggests that it was created, and abandoned, as a copying exercise, since it contains numerous corrections and errors. The text refers to both Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po) and Tri Song Detsen (Khri srong lde brtsan), and to a period of subsequent decline. van Schaik (2010) suggests composition between the mid ninth and late tenth centuries. The text is written in verse, in seven-syllable lines. It is introduced as concerning the scripture (dar ma) that fell from the sky.

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

The original manuscript is held in the British Library IOL Tib J 370 (5)

References

A transliteration is found in Richardson, Hugh. 1977. “The Dharma that Came Down from Heaven”: A Tun-huang Fragment. In L.S. Kawamura and K. Scott (eds), Buddhist Thought and Asian Civilization: Essays in Honor of Herbert V. Guenther on his Sixtieth Birthday. Emeryville, CA: Dharma, pp. 219–29 (also reproduced in: 1998. High Peaks and Pure Earth: Collected Writings on Tibetan History and Culture, (M. Aris, ed.) London: Serindia Publications, pp. 74–81).

The text and its relation to later traditions is discussed in Stein, R.A. 1986. Tibetica Antiqua IV: La Tradition Relative au Début du Bouddhisme au Tibet. Bulletin de l'Ecole Francaise d'Extreme-Orient. 74: 169–96.

See also:

Dotson, Brandon. 2006. Administration and Law in the Tibetan Empire: the Section on Law and State and Its Old Tibetan Antecedents. D.Phil. Thesis: Oxford University. pp. 340–41.

Kapstein, Matthew. 2000. The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism: Conversion, Contestation, and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 57–58

van Schaik, Sam. 2010. Dharma from the Sky: Self-Appointed Buddhas, posted online, 24 Sept 2010.

Extracts

There is considerable uncertainty over the correct translation of several parts of the text. The version offered here has made use of Kapstein (2000: 57–58), Dotson (2006: 340–41), and van Schaik (2010).

In the first 18 lines it is recorded that Songtsen Gampo, described as ‘divinely manifested’, and Tri Song Detsen, received the doctrine of Gautama Shakya (’Ge’u tam shag kya’i bstan pa) and caused it to spread. In order to ensure its endurance, the lord and subjects wrote an inscription on a pillar. The text continues:

།གཙུག་ལག་འདི་ལྟར་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ལ།

།རྗེ་འབངས་སྤྱོད་པ་ལྷུན་བོའི་རིས།

།འདི་མཛད་གཞུང་བཙུགས་རིང་ལོན་ཏེ།

།མངའ་རིས་མཐའ་སྐྱེས་བོད་ཁམས་བདེ།

In the ocean of the order established in this way;

the deeds of the ruler and subjects were the world-mountain.

When these activities were well established (gzhung btsugs);

the bounds of the dominion increased and Tibet and Khams were happy.

།ལོ་ལེགས་མྱི་ནད་ཕྱུགས་ནད་དཀོན།

།འབངས་ཀྱང་ཆབ་གང་ལུགས་ཆེ་སྟེ།

།ལྷ་ཆོས་མྱི་ཆོས་འཛེམ་བས་ན།

།བཀུར་ཞིང་གཟུང་སུ་ཆེར་བཟུང་ནས།

།སློབས་པོན་ཕ་མ་ཕུ་ནུ་གཉེན།

།རྒན་ཞིང་གོང་མ་མཐོ་བ་ལ།

།འཇམ་དེས་སྲི་ཞུ་ཚུལ་མྱི་ནོར།

།ཀུན་ལ་ངའ་བྱམས་པའི་སེམས་ཡོད་པས།

།གཞན་ལ་རྐུ་འཕྲོག་མྱི་བྱེད་ཏེ།

།བརྫུན་དང་འཕྱོན་མ་ངོ་ཚ་འཛེམ།

།དྲང་བརྟན་དཔའ་རྟུལ་ཆུ་གང་ཆེ།

།མྱི་ལུས་ཐོབ་ཀྱང་ལྷའི་ལུགས།

།རྒྱལ་ཁམས་གཞན་དང་མྱི་གཞན་ལ།

།སྔོན་ཡང་མྱི་སྲིད་ཕྱིས་མྱི་འབྱུང་།

དེ་བཞིན་ལྷ་ལ་དཀོན་བ་ཡིན།

Harvests were good and diseases of men and livestock were rare.

The moral qualities and behaviour (chab gang lugs) of the people increased.

Rather than shunning the principles of the divine and human customs (lha chos and mi chos),

they honoured and adhered to them closely.

Teachers, parents, clansmen, kinsmen,

elders, and those in high positions,

were always treated in a respectful and gentle manner.

Because they had a kind attitude towards everyone,

people did not steal from or rob one another,

they avoided lying and shameful sexual misconduct.

They were honest, steadfast, truthful, and courageous.

Although they had the bodies of men, their customs were divine (lha’i lugs);

they were unprecedented in other kingdoms and among other men and are unlikely to occur again.

They were as rare as deities.

།རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡབ་ནོངས་སྲས་ཆུངས་པས།

།ཆོས་བཟང་གཙུག་ལག་རྙིང་ནུབ་མོད།

།བདེན་བའི་ལམ་མཆོག་དགེ་བའི་ཆོས།

།འདུལ་བའི་དགེ་བཅུ་སྲུང་བ་དང་།

།མྱི་མགོན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་དང་།

།ཕྱ་མྱེས་འཛངས་པའི་སྟན་ངག་གཞུང་།

།བོད་ཀྱི་ལུགས་ལྟར་ག་ལ་བྱེད།

The king died when his son was small

and the former order with its good customs (chos bzang gtsug lag), declined.

The supreme path of truth and the practice of virtue;

adherence to the discipline (’dul ba) of the ten virtues [the Vinaya];

the laws of the king (rgyal khrims), protector of men;

the oral teachings of wise forebears:

how could these be practised in accordance with Tibetan customs?

In the last three lines, the text refers to self-originating, or self-appointed, Buddhas that come into being unannounced, or unauthorized, and to the separate traditions of the zhu, the chos, and the Vajrayāna, before breaking off.