The Red Annals

Deb ther dmar po rnams kyi dang hu lan deb ther

Introduction

The author, Tsalpa Kunga Dorjé (Tshal pa Kun dga' rdo rje, 1309–1364), was a member of the Tsalpa (Tshal pa) family, who were powerful in Central Tibet before the rise of the Lang (Rlangs) family. The Lang leader, Ta’i Situ Jangchub Gyaltsen (Byang chub rgyal mtshan) (1302–1364) was effectively ruler of central Tibet after 1354. Kunga Dorjé spent a considerable amount of time in the Mongols’ Yuan dynasty court, going there first at a young age, in 1324. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all served in the Yuan court. In his final years Kunga Dorjé entered monastic life in Tibet. He began writing The Red Annals in 1346 and completed it in 1363.

The work itself has been described as ‘the earliest extant Tibetan example of an attempt at writing a global history’ (van der Kuijp 1996: 44) and as ‘an important source on Buddhism under the Mongol Yuan dynasty as viewed by a learned Tibetan monk’ (Franke 1990: 37).

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

The edition generally used by current scholars was published in Beijing in 1981, with extensive notes in Tibetan by Dungkar Lozang Trinlé (Dung dkar blo bzang phrin las). In the introduction he states that nine examples of the text were known at the time of publication. Although written in Tibetan, the title of the work was originally Hu lan deb ther, a transcription of the Mongolian title.

It has been suggested that some parts of the text are later additions (Petech 1990: 2; Gamble 2014, Appendix 2).

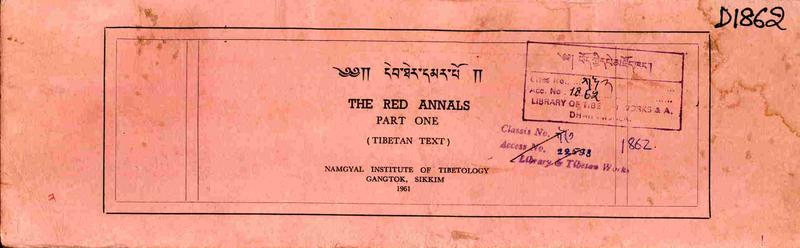

Deb-ther dmar-po. 1961. Gangtok: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology.

Deb-ther dmar-po. 1981 (re-printed 1993). Dung-dkar bLo-bzang Phrin-las (ed.) Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang. BDRC: W1KG5760.

References

Bira, Šhagdaryn. 1964. Some remarks on the Hu-lan deb-ther of Kun-dga’ rdo-rje, Act Orientalia Hungarica 18: 69–81.

Czaja, Olaf. 2013. Medieval Rule in Tibet: The Rlang Clan and the Political and Religious History of the Ruling House of Phag mo gru pa. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Franke, Herbert. 1990. Comments on a Passage in the Hu-lan deb-ther: the “Edict of Öljeitü” on the Punishment of Attacks against Tibetan Monks. In P. Daffina (ed.) Indo-Sino-Tibetica: Studies in Onore di Luciano Petech. Rome: Bardi Editore.

Gamble, Ruth. 2014. The View from Nowhere: The Travels of the Third Karmapa, Rang Byung Rdo Rje in Story and Songs. PhD. Thesis: Australian National University.

van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1996. Tibetan Historiography. In J. Cabezón and R. Jackson (eds), Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre. Ithaca: Snow Lion, pp. 39–56.

—. 1993. “Jambhala: An Imperial Envoy to Tibet during the Late Yuan.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 113 (4): 529-538.

Petech, Luciano. 1990. Central Tibet and the Mongols: The Yüan-Sa-skya period of Tibetan history. Rome: IsMEO.

Rerikh, Yū N. (J. Nattier, trans.) 1973. Mongol-Tibetan Relations in the 13th and 14th Centuries, In Tibet Society Bulletin 6: 40–55.

Schuh, Dieter. 1977. Erlasse und Sendschreiben mongolischer Herrscher für tibetische Geisliche Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Urkunden des tibetischen Mittelalters und ihrer Diplomatik. Sankt Augustin: VGH Wissenschaftsverlag.

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1949. Tibetan Painted Scrolls. Roma: Libreria dello Stato.

Zhou Qingshu. 1984. "The Red Annals: A Book of Ancient History in Tibetan", Social Sciences in China 5 (4): 177–87.

Outline

In the 1981 edition the text is arranged into 26 chapters (over 150 pages). The first nine chapters concern the origins of the world, the life and teachings of the Buddha, continuing with accounts of royal lineages (rgyal rabs) of India, China, Xi-Xia (Tangut), Mongolia, and Tibet. The middle section deals with the history of the diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet. Later chapters are dedicated to individual sects of Tibetan Buddhism: Sakya (Sa skya), Kadampa (bKa’ gdams pa), and Kagyu (bKa’ brguyd). The final chapter concerns an edict issued by Temür Qan (1295–1307).

Extracts

The page numbers below refer to the 1981 Beijing edition and use the chapter headings in that edition.

The author, Tsalpa Kunga Dorjé, begins with his own background.

[pp. 1-2]

རང་ལོ་བཅུ་བདུན་པ་ཤིང་གླང་སྤྱི་ལོ་ལོར་ཡོན་རྒྱལ་རབས་ཀྱི་གོང་མ་ཡེ་སུན་ཐེའི་མུར་གྱི་དྲུང་བྱོན། དངུལ་བྲེ་ཆེན་དང་། དངུལ་གྱི་ཐམ་ཀ་གསེར་གྱི་རྒྱན། གོས་དར་སོགས་མང་པོ་དང་། ཚལ་པའི་མི་སྡེ་དབང་རིགས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཤེས་སུ་བཅུག་པའི་འཇའ་ས་བཅས་བྱུང་།

At the age of 17, in the wood ox year [1324], I came before the emperor of the Yuan royal lineage, Ye sun the’i mur. [There I] received large quantities of silver, a silver seal, golden ornaments, and many sorts of silk clothing, together with an edict (’ja’ sa), which specified all the powerful men of the Tshal pa family.

Chapter Five: Translations of Tang Chinese sources on Tibet

One story concerns a queen named Wu san.

[p. 20]

ཕྱིས་མོ་རྒས་དུས་ཐང་གི་བརྒྱུད་མེད་པས། མོའི་མིང་པོ་ཝུ་སན་ཞེས་པ་བསྐོ་བར་བྱས་མི་མང་པོ་ཚོགས་པ་ལ། ཝུ་སན་བསྐོ་བ་ཨེ་འཐད་སྐད་རིངས་གཏོང་བས། གང་མི་འཐད་ཟེར་བ་དེ་གསོད་པའི་རྒྱལ་མོའི་འཇའ་ས་བྱས་པ་ལ།

Subsequently, when she was older, the Tang dynasty ceased. She was appointed under the name Wu san. At a gathering of many people, it was briefly asked whether it was right to have appointed Wu san. When they said it was not right, an edict was issued for the execution of the queen.

Chapter Nine: The Tibetan royal lineage

This section concerning Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po) recounts the way in which he founded temples in Tibet. It lists ministers and religious teachers from India and elsewhere and describes the translation of religious texts.

[p. 35–36]

ཐོན་མིས་རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་ཡི་གེ་ལ་དཔེ་བྱས་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་ཡི་གེ་བརྩམས། བོད་འབངས་ལ་དགེ་བ་བཅུའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅས་མི་ཆོས་གཙང་མ་བཅུ་དྲུག་གི་སྲོལ་བཙུགས། བོད་དུ་བཞི་སྟོང་སྡེ་ཕྱེ།

Thon mi [sam bho ta] created the Tibetan letters, using the Indian letters as an example. [The king] made laws based on the ten virtues (dge bcu’i khrims bcas) and introduced the practices (srol) of the sixteen pure human customs (mi chos gtsang ma) for the Tibetan people. Tibet was divided into four stong sde (thousand communities).

Chapter Twenty-Three: The history of the Karma Kagyu

After passages on the First and Second Karmapas, the chapter continues with an account of the activities of the Third Karmapa (1284–1339).

[p. 101]

ལུང་བསྟན་བཞིན་ཤར་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཐོག་ཐི་མུར་གྱི་སྤྱན་འདྲེན་ལ་མགོན་པོ་ཚལ་ཆིང་འཇའ་ས་དང་འབུལ་བ། ཀརྨ་པཀྴིའི་གསེར་གྱི་ཐམ་ཁ་དང་བཅས་པ་བསྐྱུ་བཏང་ནས་ལུག་ལོ་ཟླ་བ་བདུན་པ་ལ་བཏེགས་ནས། དབུས་སུ་བྱོན།

In accordance with the prediction, on the invitation of the eastern king Thog thi mu,1 he was offered a mgon po tshal ching edict (’ja’ sa). Having received the golden seal of Karma Pakshi, and taking it with him, he went to dBus in the seventh month of the sheep year.2

[p. 102]

ཆོས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱི་སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་རྟོགས་པའི་ཀརྨ་པ་ཞེས་པའི་མཚན་གྱི་འཇའ་ས་གུ་ཤྲཱི་དམ་ཁ་ཤེལ་གྱི་སྦེལ་ཁ། གསེར་ཡིག་སྒོར་མོ་ཕུལ།

An edict (dam kha) was issue by Gushri in the name of the Karmapa, known as the one who has realized the emptiness of all phenomena, with a crystal seal and a travelling pass.3

Later, the Third Karmapa is concerned with religious practices and fallacies (skyon), which need to be put right. He issues an edict in this regard:

[p. 105]

ཅི་ཙམ་དར་གན་ལ་འདོན་འཇའ་ས་ཕྱོགས་ཐམས་ཅད་དུ་བསྒྲགས།

Wherever it was read out, an edict (’ja’ sa) was proclaimed in all directions.

The chapter continues (from p. 108) with the activities of the Fourth Karmapa (1340–1386). It describes how, as a child and teenager, he completes his education in Central Tibet, and at nineteen years old is invited to the Yuan court by the last emperor of the dynasty, Toghun Temür (r. 1333–1368). The emperor is delighted to renew his relationship with a reincarnation of his former teacher.

[p. 111]

རྟོག་དཔྱོད་ཅན་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱིས་དེ་ལྟར་གཏམ་ཀིན་འདུག་ཞུས་པས། གོང་མ་ཕྱག་ཐལ་མོ་སྦྱོར། སྤྱན་ཆབ་བྱོན་ནས། གདན་འདྲེན་གྱི་འཇའ་ས་སྙན་ངག་ཆེན་མོ་བོད་ཡིག་མ། རྟེན་གསེར་བྲེ་གཅིག དངུལ་བྲེ་གསུམ། གོས་དར་དགུ་ཚན་གསུམ་དང་བཅས་པ་བསྐུར་ནས་

All the philosophers asked him to stay.4 The emperor (gong ma) put his hands together and shed tears. He gave [the Fourth Karmapa] a poetically written letter (’ja’ sa) of invitation to stay, in Tibetan script, along with three gifts: a bre of gold, three bre of silver, and nine rolls of silk cloth.

The chapter describes how the Fourth Karmapa travels around and is invited to many places, being offered gold, silver, and silk cloth.

[p. 118]

ཤིང་ཀུན་ཏུ་བླ་མ་འཇམ་དབྱངས་པས་གསེར་ཡིག་པ་དམག་སྡེའི་སེམས་ཅན་ལ་གནོད་འཚེ་བྱུང་ན་གདན་མི་འདྲོངས། དེ་རྣམས་མེད་ཀྱང་། འཇའ་ས་བྱོན་ཞིང་ལམ་བདེ་ན་གདན་འདྲོངས་པའི་ཁག་ངེད་ཀྱིས་འཁུར་ཟེར་བ་བྱས་ནས་གདན་འདྲེན་གྱི་འཇའ་ས་དང་ཀར་མ་ལྷ་སྡིང་པས་བསྐོས་འཇའ་བསྲུང་བྱ་རྣམས་ཁོང་གིས་ཁྱེར་ཡོངས་ནས་ཆོས་རྗེའི་དྲུང་དུ་ཕུལ་འདུག

At Shing kun, bLa ma ’jam dbyangs said that he would not welcome the officials (gser yig pa) if the army was likely to cause harm to sentient beings. Nevertheless, he said that if a ’ja’ sa arrived in a peaceful manner, he would accept the difficulties of the invitation. A ’ja’ sa of invitation issued by Kar ma lha sding, brought by the ’ja’ protectors themselves, was offered to the dharma lord [the Fourth Karmapa].

[p. 119]

ཆོས་རྗེ་པ་ཉིད་ལ། ཐུ་ལུ་ཤྲི་སྐྱའོ་ཏའོ་དབེན་གུ་ཤྲཱི་ཡི་ཤེལ་གྱི་དམ་ཁ་གནང་། ཉེས་པ་ཅན་སྤྱི་ཐར་བའི་ཤེལ་འཇའ་ཆེན་པོ་ཞུས་ནས་བོད་དུ་སྒྲོག་པ་ལ་སྡེ་དཔོན་དཀོན་མཆོག་རྒྱལ་མཚན་བཏང་། བསྟན་པ་ཤེད་བསྐྱེད་པའི་འཇའ་ས་ཁྱད་པར་དུ་རྒྱལ་བུ་ཆེན་པོའི་ལིང་ཇི་ན།

The dharma lord himself [the Fourth Karmapa] was given the crystal seal of Thu lu shri skya’o ta’o gu shri. He requested a crystal edict (shel ’ja’ sa) for the release of prisoners and the commanders were given banners with auspicious symbols on them, in order to make [the edict] known in Tibet.5

Chapter Twenty-Four: concerning the Pagmodru (Phag mo gru) and Drigung Kagyu (ʼBri gung bka’ brgyud).

This chapter describes the activities of the Phagmodru leader, Ta’i Situ Jangchub Gyaltsen. There are references to ’ja’ sa (edicts) confirming official appointments, such as that of khri dpon (head of one of the major Tibetan districts). It continues with a synopsis of Drigung Kagyu history, ending with a brief description of the life of Lha Rinchen Gyalpo (Lha rin chen rgyal po) in the fourteenth century.

[p. 126]

ཁུ་བོའི་གདན་སར་ལྷ་ནང་དུ་བཞུགས་པས་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་འཆལ་བའི་དམག་སྣའི་གནོད་པ་བྱུང་བས་སྐྱི་སྨད་ཀྱི་ས་ཆར་བྱོན་ནས།

When he [Lha Rinchen Gyalpo] was staying at his uncle’s place at lHa nang, he was harmed by the vanguard of the army, which disregarded the royal law (rgyal khrims), so he went to sKyi smad.

Chapter Twenty-Five: concerning the Tsalpa Kagyu.

The chapter describes the activities of Zhang Rinpoche (1123–1193), founder of the Tsalpa Kagyu. He establishes monasteries at Tsalpa in 1173 and at Gungtang (Gung thang) in 1187. He also commissions the large lHa chen dpal ’bar statue of Śākyamuni at Tsal Gungtang. The author extols Lama Zhang's spiritual achievements and qualities, with no mention of his violence.

[p. 128]

གཉའ་དང་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་མཛད།

He [bLa ma Zhang] established the yoke (gnya’) and the royal law (rgyal khrims).

Chapter Twenty-Six: An edict (ʼja’ sa) from the time of the emperor Öljeitü (Ol ja thu) of the Yuan royal lineage concerning an increase in the clerical authority bestowed on the monks of Tibet.

This chapter describes an edict made in 1297 by the Yuan emperor, Öljeitü (Ol ja thu), also known as Temür (r. 1294–1307).

[pp. 149]

ཨོལ་ཇ་ཐུ་རྒྱལ་པོའི་དུས། ཚེ་རིངས་གནམ་གྱི་ཤེ་མོང་ལས་བསོད་ནམས་ཆེན་པོའི་དཔལ་ལ་བསྟེན་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་ངེད་ཀྱི་ལུང་། ཏྲུང་ཤུ་ཞིང་གི་མི་དཔོན་རྣམས་ལ། ཆུ་མི་དབེན་གྱི་མི་དཔོན། གཡུ་ཤྲི་ཐའི་མི་དཔོན་ལ། ཧྱིང་ཛུ་ཤྲི་ཞིང་། ཧྱིང་གཡུའི་ཤྲི་ཐའི་མི་དཔོན། གླེ་ཧྭོང་སིའི་མི་དཔོན་མཁར་དཔོན་དང་ཡུལ་བསྲུངས་རྣམས་ལ། དམག་དཔོན། དམག་མི་རྣམས་ལ། ཚན་པ་ཚན་པའི་རྒན་པ་རྣམས་ལ། མི་སྡེ་མང་པོ་ལ་གོ་བར་བྱེད་པའི་ལུང་།

During their reign of King Ol ja thu, under the inherent authority of everlasting heaven and from an abundance of great merit, our king’s edict [was pronounced as follows]:

To the chief administrator of the Central Secretariat (hrung shu zhing); the officials of the Board of Military Affairs (chu mi dben); the officers of the Censorate (g.yu shri tha); the officers of the Branch Secretariats (hying dzu shri) and the Branch Censorates (hying g.yu’i shri tha); the officers of the Surveillance Bureau (gle hwong si); the city governors and the regional protectors; the army commanders and the army personnel; the elders of the various communities: this edict is to be made known to many people.6

[p.150]

ཇིང་གིས་རྒྱལ་པོ་དང་། ཨོ་གོ་ཏ་རྒྱལ་པོས། ཤཱཀྱ་མུ་ནེའི་ཆོས་ལུགས་བཞིན་དུ། བནྡེ་ཇི་འདྲ་ཡིན་ཀྱང་། ཁྲལ་དམག་ལས་གསུམ་མ་ལེན་དུ་ཆུག གནམ་མཆོད་ཅིང་སྨོན་ལམ་འདེབས་པའི་དོན་ལ་ངེད་ཀྱིས་བདག་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན་བྱས་འདུག

The King Jing gis (Chinggis Qan) and the King O go ta (Ögodei Qan) are said to have directed that tax, military conscription, and labour obligations are not to be imposed on any monks who follow the doctrinal tradition of Śākyamuni, so that [they] may make religious offerings and say prayers.

སེ་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་པོས་དཀོན་མཆོག་གསུམ་ལ་མོས་གུས་བྱས་པའི་དོན་ལ། སངས་རྒྱས་ཤཱཀྱ་མུ་ནེའི་ཆོས་འཇིག་རྟེན་དུ་ཀུན་གྱི་ཐོག་ཏུ་འགྲིམ་དུ་བཅུག་འདུག་པ་བཞིན། ངེད་ལ་སྨོན་ལམ་འདེབས་པ་དང་ཆོ་ག་བྱེད་དུ་ཆུག བཟླས་པ་ཡིན་ནའང་། ཟུར་དུ་མཁར་མིག་ལ་བསྐོས་པའི་མི་དཔོན་དང་མི་སྡེ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་མ་གོ་བའི་དོན་ལ། ལྷ་ཁང་། དགོན་སྡེ་ལ་ཤེ་མོང་བཙོངས་པ་དང་། བནྡེ་ལ་ཤེ་མོང་བཙོང་པ་ཡོད་དེ་ཡོང་། ད་ཡིན་ན། མི་སྡེ་ཤེས་པའི་མི་དཔོན་དང་། མི་སྡེ་མང་པོས། ད་ཕྱིན་ཆད། ཤཱཀྱ་མུ་ནེའི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་ལུགས་བཞིན་འགྲིམ་དུ་ཆུག བནྡེ་ལ་ཤེ་མོང་མ་བཙོང་དུ་ཆུག ལྷ་ཁང་དང་དགོན་སྡེ་ལ་ཤེ་མོང་མ་བཙོང་བར་ཞབས་ཏོག་བྱེད་དུ་ཆུག

As King Se chen (Qubilai Qan) was devoted to the Three Jewels, he also caused the doctrine of the Buddha Śākyamuni to spread throughout the world. Although he told people to pray and perform rituals for him, because people appointed elsewhere as city officials (mkhar mig) and community leaders did not understand, they flouted the inherent authority of the temples and monasteries and they will flout the inherent authority of the monks. In the circumstances, the leaders responsible for the people, and the mass of people should follow the doctrinal tradition of Śākyamuni. The inherent authority of the monks should not be flouted, the inherent authority of the temples and monasteries should not be flouted, and they should be honoured.

[p. 150–51]

བོད་ཀྱི་བནྡེ་རྣམས་ལ་ཞབས་ཏོག་བྱེད་པའི་དོན་ལ། སེ་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་དུས་སུ། ཉེས་པ་སྡོད་པའི་མཁར་ལ་ཡོད་པའི་མ་མིང་ཟེར་བ་གཅིག་གིས་དགེ་སློང་གཅིག་གི་གོང་རྩ་ནས་བཟུང་བའི་དོན་ལ། མི་དེ་ཉེས་པ་ལས་བཏུགས་པ་ཡིན། ད་ཕྱིན་ཆད་བོད་ཀྱི་བནྡེ་རྣམས་ལ་མི་སྐྱས་ལག་གི་སླེབས་ན་ལག་པ་བྲེགས། ཁས་སླེབས་ན་ལྕེ་ཐོན། འཇའ་ས་འདི་ལྟར་སྒྲགས་ཕྱིན་ཆད། བནྡེ་ལ་བསྐུར་ཆ་མི་བྱེད་པ་དང་། ལྷ་ཁང་དང་དགོན་པ་ལ་ཤེ་མོང་འཚོང་བའི་མི་དེ་ཕྱོགས་ཕྱོགས་སུ་བསྐོས་པའི་མི་དཔོན་དང་། བནྡེ་རྒན་པས་ཟུང་ལ། ངེད་ཅན་ཁྱེར་ཤོག་ཇི་ལྟར་བྱེད་ངེད་ཀྱིས་གོ་བར་བྱེད་པ་ཡིན། ངེད་ཀྱི་འཇའ་ས་འདི་བྱ་ལོ་དཔྱིད་ཟླ་ཐ་ཆུངས་ཀྱི་ཉེར་བརྒྱད་ལ་ཤང་ཏོ་ན་ཡོད་དུས་བྲིས།

In order to ensure that the monks were honoured, during the reign of King Se chen (Qubilai Qan), when a certain wicked city-dweller assaulted an ordained Buddhist monk, he was prosecuted for the fault. From now on, if a lay person so much as touches a Tibetan monk, his hand is to be cut off; if he touches him verbally, his tongue is to be torn out. Once this edict (ʼja’ sa) has been proclaimed, people who do not respect the monks and flout the inherent authority of the temples and monasteries, wherever they may be, should be seized by appointed officials or senior monks, and they must be brought before me. This is to be understood.

This is my edict, made on the twenty-eighth day of the last month of spring in the bird year [1297], at Shang to.

Footnotes:

- Dung-dkar (1981: 418, n. 483) states that this king was the tenth in the Yuan lineage and ruled from 1328 to 1331. ↩

- This would be 1331. ↩

- This may be what was known as a paiza, after the Chinese term. ↩

- The meaning of gtam kin is obscure. ↩

- Czaja (2013: 171, n. 193) interprets this as referring to a general amnesty that Rol pa’i rdo rje requested from the Chinese emperor in 1361, which was then publicly proclaimed in Tibet. ↩

- The bureaucratic terms in this passage are transcriptions of Chinese terms, with tentative translations based on Bira (1964) and Schuh (1977). ↩