The Great Sino-Tibetan Archives

Rgya bod yig tshang chen mo

Introduction

This history is also known as the Rgya bod yig tshang mkhas pa dga’ byed chen mo ʼdzam gling gsal ba’i me long. It was written by Tagtsang Dzongpa (sTag tshang rdzong pa dpal ʼbyor bzang po), who was probably a lay official at the Dus mchod bla brang of the Tagtsang fort. This had been established by a branch of the Sakya Khon (Sa skya ’khon) family in the fourteenth century. The text was completed in around 1434, during a period of unrest in central Tibet, when the Rinpung (Rin spungs) family began to wrest power from the Phagmodru (Phag mo gru).

The text consists of a history of China and Tibet, with emphasis on the activities of the Sakya.

Download this resource as a PDF:

Sources

All versions seem to be based on a single manuscript, kept by the Densapa family in Gangtok.

—. 1979. Munzang Tobgey and Manii Dorji (eds), Thimpu (2 vols) (manuscript version).

rGya bod yig tshang chen mo. 1985. Chengdu: Mi-rigs Dpe skrun khang. (Introduction by Dungkar Lobsang Trinley) BDRC: W20848.

References

Choi, Soyoung. 2019. Annotated Translation and Study of Archives from China and Tibet (Rgya bod yig tshang) [최소영. (15 세기 티베트 저작 [漢藏史集 (Rgya bod yig tshang)] Doctoral dissertation. https://hdl.handle.net/10371/162335

Everding, Karl-Heinz. 2007. “Tradition und Umbruch in der tibetischen Geschichtsschreibung: Die Darstellung der Entstehung und des Aufstiegs der Zehntausendschaft Zha lu nach dem rGya bod yig tshang.” In Tibetstudien: Festschrift für Dieter Schuh zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Dieter Schuh, Petra H. Maurer and Peter Schwieger, 55–93. Bonn: Bier’sche Verlagsanstalt.

—. 2017. “Gyantse: Rise, Prime and Decline of a Tibetan Principality in the 14th16th Centuries.” In Fifteenth Century Tibet: Cultural Blossoming and Political Unrest, edited by Volker Caumanns and Marta Sernesi, 33–62. Lumbini: LIRI.

Macdonald, Ariane. 1963. Préambule à la lecture d’un Rgya-Bod yig-chan, Journal Asiatique 251: 53–159.

Martin, Dan. 1997. Tibetan Histories: A Bibliography of Tibetan-language Historical Works. London: Serindia, p. 68.

Outline and Extracts

The text is that of the 1985 edition, with references to its page numbers. The chapter headings are also those of that edition (and different from those used by Macdonald, which follow the text’s own introduction). The 1985 edition is divided into two volumes, and runs to 608 pages.

The first eight chapters concern Chinese, Tibetan, and Indian royal genealogies and the history of the Buddhist doctrine in India.

The royal line of Nepal

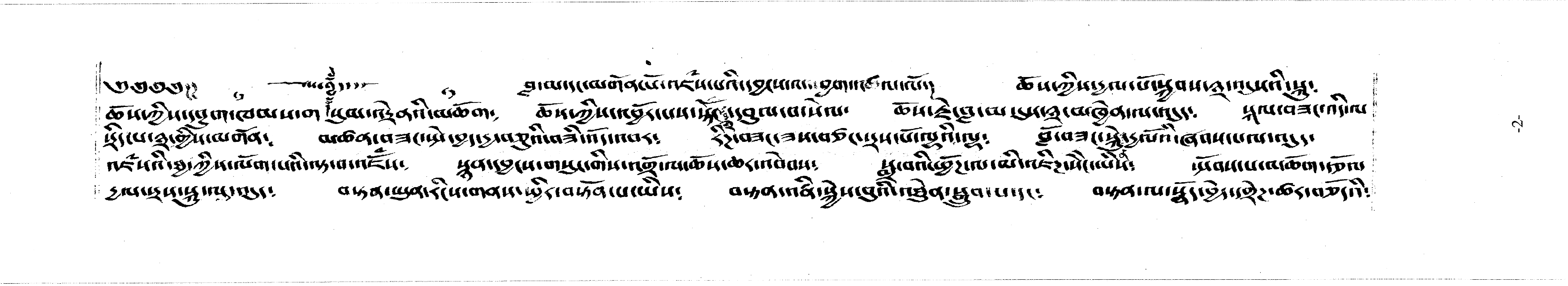

བལ་བོའི་༼ལི་ཡུལ་༽ རྒྱལ་རབས་བཞུགས།

[p.84]

ན་མོ་ཨརྱ་མེ༼མཻ༽་ཏྲི་ཡེ།

བྱམས་དང་ཐུགས་རྗེས་སྲིད་གསུམ་འགྲོ་བ་ཡི།

།མགོན་གྱུར་ས་བཅུའི་དབང་ཕྱུག་ཞབས་བཏུད་ནས།

།དེའི་སྤྲུལ་པས་བསྟན་པ་རྒྱས་མཛད་ཅིང༌། །མི་ཡུལ་ཆགས་འཇིག་ཁྲིམས་གཉིས་གནས་ཚུལ་བཤད།

Namo, Ārya Maitreya,

I bow to the feet of the master of the ten levels,

Who with kindness and compassion has become protector of the three realms of beings.

[Maitreya's] manifestation has spread the Buddhist teaching and explained the operation of the dual laws, which govern creation and destruction within the human realm.

The passage continues by extolling the virtues of Nepal (here referred to as Li yul), with its Buddhist connections, from as far back as a Buddha prior to Śākyamuni.

This chapter is followed by genealogies from China and Minyak (Tangut). There is then a long chapter on the kings of Tibet.

The royal line of the religious kings of Tibet

ཆོས་རྒྱལ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་རབས་བཞུགས་སོ།

King Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po) orders the creation of a Tibetan script and the translation of Buddhist texts. He withdraws for four years within the palace in order to study them, in particular those concerning Āvalokiteśvara.

[pp.144–45]

།དེ་དུས་རྒྱལ་པོས། ལོ་བཞིར་སྒོར་མ་བྱོན་པ་དེས། བློན་པོ་རྣམས་ན་རེ། རྒྱལ་པོས་ཅི་ཡང་མི་ཤེས། བོད་ཁམས་བདེ་བ་འདི། ངེད་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་བྱས་པ་ཡིན་ཟེར་བ། རྒྱལ་པོས་གསན་ནས། ང་གླན་༼གླེན༽་པར་རྩི་ན། བོད་མི་ཐུལ་དགོངས་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོའི་རིགས་དེ་ས་གཅིག་ཏུ་གནས་ན། ཀུན་བདེ་བ་ཡིན་ཏེ། སྔོན་ཡང་ཁྲིམས་མེད་པས། ཤེས་པ་ཅན་གྱི་མི་བཅུ་གཉིས་མཐར་འཁྱམས་འདུག ད་ངས་ཆོས་ཁྲིམས་དགེ་བ་བཅུ་ལ་དཔེ་བླངས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་བཅའོ་གསུངས་ནས།

At the time, the king, not having been outside for four years, heard the ministers saying, ‘The king does not know anything at all. It is we who have made the Tibetan region happy’. The king thought, ‘If I am regarded as stupid, Tibet will not be pacified (thul)’. He said, ‘If the family of the king stays in one place, everyone will be happy. Previously when there was no law, the twelve tribes—known to us—used to wander around. Now I have established law, which follows the pattern of the religious law of the ten virtues.’

[p. 145]

བསད་པ་ལ། སྟོང་སྲང་ཉིས་ཁྲི་ཆིག་སྟོང༌། རྐུས་པ་ལ་བརྒྱད་ཅུ་འཇལ། བྱི་བྱས་པ་སྣ་གཅོད་པ། རྫུན་ཕྲ་མ་སྨྲ་བའི་ལྕེ་འབྲེག

For killing, compensation was twenty thousand to one thousand srang; for theft, compensation (ʼjal) was eighty; for adultery, cutting off the nose; for telling slanderous lies, cutting out the tongue.

ཡང་། མི་ཆོས་གཙང་མ་བཅུ་དྲུག་གིས། ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་གཞི་བཟུང་བར་བྱས་ཏེ། དཀོན་མཆོག་ལ་དད་པ་སྐྱོང་ངས་མེད་པ་དང་གཅིག དོན་དམ་པར་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་ཆོས་བཙལ་ཞིང་བསྒྲུབ་པར་བྱ་བ་གཉིས། གཙུག་ལག་དང་ཆོས་ལ་མཁས་བློ་སྦྱངས་པ་དང༌གསུམ། ཕ་མ་ལ་དྲིན་ལན་རླན་པ་དང༌བཞི། ཡོན་ཏན་ཅན་དང་རིགས་ཀྱི་རྒན་པ་ལ་བཀུར་སྟི་བྱ་བ་དང༌ལྔ། ཤ་ཉེ་དང་མཛའ་ཤེས་ལ་གཞུང་དྲང་པོར་བསྲང་ཞིང༌དང་དུ་བླངས་པ་དང་དྲུག མ་བརྟག་ཅིང་མ་བཅོལ་བའི་ལས་ལ་རྟོགས་འདོད་མེད་པ་དང༌བདུན། ཡུལ་མི་ཁྱིམ་མཚེས་ལ་ཕན་བཏགས་པ་དང༌བརྒྱད།

Further, the sixteen pure human qualities (mi chos gtsang ma bcu drug) established the foundation of the laws: first, people should unquestioningly maintain faith in the Three Jewels; second, seek the true Buddhist doctrine and practise it; third, study to be learned in the sciences and the doctrine; fourth, keep renewing their gratitude to their parents;1 fifth, respect worthy people and the elders of their families; sixth, observe the norms of honesty and straightforwardness with relations and friends; seventh, not concern themselves with matters that they do not understand and which are not entrusted to them; eighth, be helpful to their neighbours.

[p. 145–46]

གཞི་དྲང་པོར་བསྲང་ཞིང་ཁོང་སེམས་ཆུང་བ་དང༌དགུ བྱ་ལས་དང་བྱེད་སྤྱོད་ཐམས་ཅད་ཡ་རབས་ཀྱི་རྗེས་རྙོག༼སྙེག༽་ཅིང༌ཕྱིར་མི་རིང་དུ་བལྟ་བ་དང༌བཅུ། དྲིན་ཆེན་མི་ཡི་གཅད་ཅིང་ལན་རླན་པ་དང༌བཅུ་གཅིག བུ་ལོན་དུས་སུ་འཇལ་ཅིང༼ཞིང༽་བྲེ་སྲང་ལ་གཡོ་མི་བྱ་བ་དང༌བཅུ་གཉིས། ཐམས་ཅད་ལ་སྙོམས་པར་བྱ་ཞིང་འགྲན་སེམས་མི་བྱ་བ་དང༌བཅུ་གསུམ། གྲོགས་ཀྱི་ནང་དུ་བུད་མེད་ཀྱི་ཁ་ལ་མི་ཉན་ཅིང༌། རང་ཚོད་ཟིན་པར་བྱ་བ་དང༌བཅུ་བཞི། བྱ་བ་ཐམས་ཅད་ཁོངས་འཛང༼མཛངས༽་ཞིང་ངག་འཇམ་པའི་ཁོ་ནས་བསྒྲུབས་པ་དང་བཅོ་ལྔ། སེམས་ཅན་གང་ལའང་སྡང་བའི་སེམས་མི་འཆང་ཞིང་བྱམས་སྙིང་རྗེས་སྐྱོངས་བ་དང༌བཅུ་དྲུག་གོ

Ninth, be fundamentally honest and humble; tenth, emulate all the duties and behaviour of the nobility and consider them closely; eleventh, renew their gratitude for the decisions of those who are kind; twelfth, repay debts on time and not cheat with weights and measures; thirteenth, treat everyone with equanimity and not antagonise anyone; fourteenth, amongst friends, not listen to women’s talk and rely on their own judgement; fifteenth, be wise in the midst of all activity and only use gentle speech; sixteenth, not bear ill-will towards any sentient beings but treat them with love and compassion.

[p.146]

།བོད་ཀྱི་ཁྲིམས་དང༌། བོད་ཀྱི་ཆོས་དང་། ཁྲིམས་རྣམས་ཀྱི་ཤོད་ཤོ་མ་རར་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་བོ། །དེར་བློན་འབངས་རྣམས་དགའ་ནས། རྒྱལ་པོ་འདི་ཤིན་ཏུ་སྒམ་པོ་ཅིག་འདུག་གོ་ཟེར་ནས། ཁྲི་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོར་མཚན་གསོལ་ལོ།

The laws of Tibet, the religion of Tibet, and the explanation of the laws were established at Sho ma ra. Then the ministers and subjects were happy. They said, 'This king is a very profound (sgam) person', and gave him the name Khri Srong btsan sgam po.

Later in the reign of Songtsen Gampo:

[p.163]

།ར་སའི་གཙུག་ལག་ཁང་བཞེངས་ནས། ལོ་གསུམ་ལོན་ཙ་ན། བོད་འབངས་བྱིན་པོས། ནམ་ཟླ་དུས་བཞིའི་རྩིས་མ་ཤེས། བཤན༼ཤན༽་མ་ཕྱེ་བ་ལ། ཆོས་རྒྱལ་སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོའི་དགོངས་པ་ལ། ངས་ཆོས་འཇིག་རྟེན་གྱི་ཁྲིམས་འཆོས། བོད་འབངས་དགེ་ལ་བསྐུལ་ཐུབ་བྱུང་ནའང༌། འཇིག་རྟེན་པ་རྣམ་རྟོག་གི་དྲ་བ་སེལ་ཐབས། རྒྱ་དཀར་ནག་གི་རྩིས་ཀྱང་རྒྱས་པར་སྤེལ་ནས། རྒྱལ་ཁམས་ལ་ཕན་གདགས་དགོས་སྙམས་པ་འཁྲུངས་ཏེ།

After the Ra sa temple was built, when three years had passed, the majority of the Tibetan subjects did not know the calculations associated with the four seasons. As the divisions had not been made, the religious king Srong btsan sgam po, thought, ‘I ought to establish religious and worldly laws. I have come to the conclusion that even though I can guide the Tibetan people towards virtue, in order to benefit the kingdom, I need to disseminate methods to address the tangle of worldly concerns, including the calculations of India and China’.

The king then establishes standards for weights and measures.

The text continues with chapters on the histories of tea and porcelain, on the kings Tri Detsugten (Khri lDe gtsug brtan, also known as Mes ag tshom, 680–743) and Tri Song Detsen (Khri Srong lde btsan, 755–797), and a history of medical knowledge in Tibet.

The period following King Tri Song Detsen up to the decline of the doctrine under Langdarma

ཁྲི་སྲོང་ལྡེ་བཙན་གྱི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་ཀྱི་འཕྲོ་ནས་གླང་དར་མས་ཆོས་བསྣུབས་པའི་བར།

This chapter concerns the early ninth century. It starts with the successor to Tri Song Detsen, Mune Tsenpo (Mu ne btsan po), who disseminates the two laws (khrims gnyis).

Tri Tsuk Detsen (Khri gTsug lde btsan) (also known as Ralpachan (Ral pa can), r.815–836), is a strong supporter and sponsor of Buddhist activity. He establishes the royal law (rgyal khrims), on the basis of the doctrine (chos).

There follows a chapter on the later spread of the doctrine (phyi dar). The account then turns to the ministers.

The history of seven wise ministers of Tibet

བོད་ཀྱི་བློན་ཆེན་མཛངས་པ་མི་བདུན་གྱི་ལོ་རྒྱུས།

The text describes a group of seven ministers, to whom it attributes social and scientific achievements: agrarian reform, irrigation issues, metallurgical discoveries, development of the Tibetan script, standardization of weights and measures, construction of bridges, and the resolution of disputes, respectively.

As regards the first, ʼDzang gi bu ru las skyes:

[pp.229–30]

།དེ་ཡིས་ཐབས་དང་ལས་ཁ་ཅི་བྱས་ན།

།བ་གླང་འབྲི་སྣག་ར་ལུག་ཁྲིམས་སུ་རྩལ༼བསྩལ༽།

།རྩྭ་ལ་ཆུན་པོ་བྱས་ནས་དབྱར་རྩི་དགུན་དུ་རྩལ༼བསྩལ༽།

།སྤང་ཐང་ཞིང་དུ་ཀློག༼སློག༽་ནས་རིའི་དོ༼ངོ༽་སྣམས༼རྣམས༽་བཟུང༌།

།དེ་ཡི་གོང་ན་བོད་ན་རྩི་ཐོག་ལོ་ཐོག་མེད།

Regarding his skills and achievements,

He initiated rules (khrims) regarding cattle, female yaks, goats, and sheep;

Stacks of hay were made, [so that] summer grass could be used in the winter;

Pastures were turned (ploughed) into fields, so that the mountain sides were cultivated.

Previously, in Tibet there had been no harvesting of hay or crops.

Regarding his son:

ཁྲི་སྙན་བཟུང་བཙན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་སྐུ་རིང་ལ།

།གཉིས་སུ་འཛངས་པ་བློན་ཆེན་ཁུའི་བུ།

།ལྷ་བུ་མགོ་དཀར་ཞེས་པ་དེ་ཉིད་བྱུང༌།

།དེ་ཡིས་ཐབས་དང་ལས་ཁ་ཅི་བྱས་ན།

།འབྲོག་གི་དོན་དང་ཞིང་གིས་ཐུལ་དུ་སྡེབས།

During the reign of Khri snyan bzung btsan

A second wise one, son of the [previous] great minister,

Known as Lha bu go dkar, appeared.

Regarding his skills and achievements,

He united the activities of the nomads and the agriculture of the farmers.

The text continues with the way he deals with irrigation, and then discusses the achievements of the other wise ministers.

As regards the seventh, Stag tshab ldong gzigs:

[p.231]

།དེ་ཡིས་ཐབས་དང་ལས་ཁ་ཅི་བྱས་ན།

།ཕྱོགས་བཞིའི་བསྲུངས་མས་སྐུའི་རིམ་འགྲོ་བྱེད།

།རྒོད་ཀྱིས་སྟོང་སྡེས་བསོ༼སོ༽་ཁའི་དགྲ་ལ་རྒོད།

།ནང་གི་འཁོད་མཉམས༼སྙོམས༽་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱིས་གསོས་སྟོང་སྤྱད།

།དེའི་གོང་ན་བོད་ན་གསོས་སྟོང་མེད།

Regarding his skills and achievements,

He invoked the female protectors of the four directions;

His generals fiercely attacked the enemies at the borders;

He equalized [the wealth of] the internal population and his laws provided restorative compensation.

Previously, in Tibet, there had been no restorative compensation.

The next chapters concern the Mongolian dynastic succession, with particular reference to the activities of these dynasties in Tibet in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The great Mongol royal lineages

ཆེན་པོ་ཧོར་གྱི་རྒྱལ་རབས།

Das sman, a Mongol official who has been asked to set up the postal relay service in Tibet, speaks to Qubilai Qan:

[p.274]

བོད་བྱ་བ། མི་ཐུ་མོར་འདུག་པ་དང༌། ཁོང་རང་གི་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ཞིག རྒྱ་ཧོར་གྱི་ཁྲིམས། ཇི་བཞིན་མ་འཇགས། སོ་ཁ་རྣམས་ཀྱང་མ་ཚུགས་པར་ཡོད་འདུག་པས། ཕར་ཕྱིར་གྱི་མཐུན་རྐྱེན་སྦྱོར་བ་དང། བྱ་བ་ཆེན་པོ་གྲུབ་པ་ཇི་ལྟར་ཡོང་ཡིན་ཟེར། ཡང་རྒྱལ་པོའི་ལུང་གིས། རང་ལ། བོད་བྱིང་པོ་འོག་ཏུ་ཆུག་ཡོད་པར་འདུག་ཟེར་བའི་གཏམ་སྙན་ཐོབ་པ་དེས་ཆོག ཆས་ཁ། ཆ་རྐྱེན་གང་དགོས་མ་ཐུངས་པ་གན་པས་བསྐུར།

‘As regards Tibet, its people are fierce. Its own royal law has been destroyed and Chinese-Mongolian law has not been introduced. Even the borders have not been settled. So how can we introduce beneficial foreign conditions and achieve great things?’ Then, the king [Qubilai Qan] declared that he had received sufficiently clear advice that Tibet was being left to deteriorate, and whatever it needed, but did not have, would be provided by his treasurer.

The emperor continues by giving orders concerning the postal stations and appoints Das sman as Sonjingwen (son jing dben). The text continues by describing his activities in different regions, after which his authority increases (son bying dben gyi khrims dar) and he is appointed as the main governor (rtsa ba’i dpon chen).

The second volume begins with a lengthy chapter on the Sakya.

The succession of the glorious Sakya Khon family

དཔླ་ལྡན་ས་སྐྱ་འཁོན་གྱི་གདུང་རབས་བཞུགས་སོ།

Here, khrims ra, literally ‘court’, indicates administrative power, and khrims is used to refer to government and administration in general. Khrims la bsgral, literally ‘liberated in law’, is used to indicate that someone is executed.

The lineage of the kings of Gyantse

ལརྒྱལ་རབས།འove and compassion. .རྒྱལ་རྩེ་ཆོས་རྒྱལ་གྱི་གདུང་རབས་བྱུང་ཚུལ།

This chapter contains a description of the religious activities of the Sharga (Shar dga’) family, rulers of Gyantse (rGyal rtse).

It describes the birth of an emanation in 1269, who has an extraordinary life. The text recounts how, by means of the two laws (chos khrims dang rgyal khrims gnyis) he achieves many things.

The chapter ends with a lengthy biographical sketch of Rabten Kunzang Pagpa (Rab brtan kun bzang ’phags pa, 1389–1442), who commissioned the famous Gyantse stupa and was alive at the time of the composition of this text.

[p.398]

བྱང་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་སྲིད་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱང༌། དེ་ཉིད་ཀྱི་བཀའ་ལུང་དང་དུ་ལེན་ཅིང༌། དེ་དག་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱི། རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱིས་བདག་པོར་གྱུར་པས་ན། སྐུའི་གཟི་འོད། གསུང་གི་ང་རོ་དང༌། ཐུགས་ཀྱི་སྟོབས་ཀྱིས་རྒྱལ་ཁྲིམས་མནོན་པ་དང༌། ཕས་རྒོལ་འཇོམས་ཚེ་ཕྱག་ན་རྡོ་རྗེ་ཡི། སྤྲུལ་པ་ཡིན་ཞེས་ཚིག་དོན་མཐུན་པར་གྲགས།

Even the rulers of the north accepted his orders and when he became master of the royal law for them all, the splendour of his person, the strength of his speech, and the power of his thought enforced the royal law and overcame his enemies. Then he became truly renowned as an emanation of Phyag na rdo rje (Vajrapani).

The text continues with further chapters on later religious and political events. There are references to the leaders of the Pagdru and Khams acting against the law (khrims ’gal mu med byed). In this section the phrases rgyal khrims chen po’i bya ba and khrims las kyi bya ba and khrims gnyis kyi bya ba are used to refer to the activities of the governors (dpon chen).

Footnotes:

- Literally, keep ‘wet’ or ‘fresh’. ↩